The Perfect Fit: Crafting a Career at the Intersection of Making, Helping, and Human Mobility

At Georgia Tech, Kinsey Herrin combines engineering, clinical insight, and purpose to create wearable devices that help people move — and live — more freely.

Kinsey Herrin is a principal research scientist in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering at Georgia Tech.

Growing up in rural southwest Georgia, Kinsey Herrin loved “making stuff.” She loved it so much that she regularly dug up muddy clay from her family’s property and the surrounding area to make ceramics.

“I’ve always loved to make things with my hands, which totally played into my career decision and where I ultimately landed,” she said.

Herrin is a principal research scientist in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering at Georgia Tech. She directs the Human Interface Design Development and Engineering (HIDDEn) lab and helps oversee studies at the Human Augmentation Core, a major facility within the Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Machines.

As a prosthetist/orthotist, Herrin creates and tests devices that help patients improve or regain mobility — from prosthetic limbs to braces of all kinds. But her role at the Institute is even more expansive. She’s at the epicenter of a research community where medical devices, studies, data, patients, clinicians, and students collide.

Her story is a testament to the power of knowing oneself — how one little girl who loved to make things grew up to build a tailor-made career at the leading edge of wearable robotics.

“In those early visits to the orthopedist, I was exposed to other people who were going through something similar or worse than I was, and that experience made me want to help people. I think being helped by so many clinicians as a kid made me want to help people too.”

A Step in the Right Direction

Riding bikes through backroad trails, floating down the Muckalee Creek, and playing softball, Herrin was always outside and constantly on the move.

Her youth was so full of physical activity that the fact she had mobility challenges might come as a surprise.

At birth, Herrin sustained nerve damage in both legs, and doctors told her parents that walking would be a challenge. She has drop foot, which means she can’t lift her foot normally when she walks. As a child, she was fitted with leg braces.

“In those early visits to the orthopedist, I was exposed to other people who were going through something similar or worse than I was, and that experience made me want to help people,” she said. “I think being helped by so many clinicians as a kid made me want to help people too.”

Herrin’s ability to have an active childhood was in part thanks to orthotists.

“I had no idea I would one day be one myself,” she said.

Finding Her Fit

Herrin meets with 13-year-old Case Neel, center, and his mother, right. Neel participates in Herrin’s pediatric exoskeleton studies.

Always a science lover, Herrin started on the path to a career in medicine — right on track with her childhood dream of serving others.

She majored in chemistry at the University of Georgia, but during a summer program shadowing physicians in a hospital, something didn’t click.

“I remember thinking, ‘Oh, I don’t think I like this,’” she said. “The making aspect was missing. I wanted to make things that would help people, and I didn’t want to see my patients only once a year. I wanted real relationships.”

Staring down the start of senior year and an MCAT exam that was weeks away, she found herself utterly unexcited about going to medical school.

That realization sent Herrin searching. She soon discovered Georgia Tech’s Master of Science in Prosthetics and Orthotics (MSPO) program and arranged a visit, followed by a shadowing opportunity at a local clinic.

In that shadowing visit, she watched a child with cerebral palsy run up and down a hallway with a customized orthotic walker, clinicians crafting prosthetic legs and arms, and others fitting devices to help people stand taller and walk with less pain.

“The work was just so diverse and so interesting, and I was amazed,” she said. “But more than anything, they were making things. I needed to build. I needed to make. I needed some art and craft built into the profession I was going into. I was instantly hooked.”

Herrin changed her plans, loaded her class schedule with 21 credit hours, and set her sights on Georgia Tech.

“It’s very rare for a medical profession to be so broad,” she said. “That’s what drew me in, that combination of science, creativity, and helping people every single day.”

“I saw my transition from teaching to research as another really amazing opportunity to chart my own course. That’s what's so cool about being research faculty here at Georgia Tech: If you have an idea, you can really explore it.”

Training and Traction

Catalina Bulla, a former patient, wearing a prosthesis designed and fabricated by Herrin.

Herrin earned her degree at Tech and completed her orthotics residency at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. There, she led her own research project to test a novel orthosis that successfully treated idiopathic toe walking, a condition in which children habitually walk on the tips of their toes. By then, it was clear that she loved translating research into real-world impact.

Herrin completed a second residency in prosthetics at the University of Michigan before beginning clinical practice as a prosthetist/orthotist in Florida, where she helped people just as she had been helped as a young girl.

After five years, she faced another critical juncture in her career path.

“As much as I loved my patients and my work, I wanted a new challenge,” she said. “I needed something to stimulate me, to try something different.”

Herrin returned to Georgia Tech to teach in the MPSO program she had enrolled in as a student. At that time, Tech’s MPSO program was winding down, and Herrin played a key role in transitioning it to Kennesaw State University, where it thrives today.

While teaching, Herrin also began volunteering on a prosthetic research project with Aaron Young, associate professor in mechanical engineering.

That collaboration bloomed, and before she knew it, she was working with pediatric and stroke patients and modifying hip exoskeletons. Eventually, she was offered a full-time research faculty role at Georgia Tech.

“I saw my transition from teaching to research as another really amazing opportunity to chart my own course. That’s what's so cool about being research faculty here at Georgia Tech: If you have an idea, you can really explore it.”

“I really try to engage with the communities we serve. I don’t want it to feel transactional. I want people to know they’re part of our team, beyond just participating in a study.”

Personal Experience, Professional Purpose

Herrin at work with a research participant and colleagues in the Hibay area at Georgia Tech’s Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Machine’s Human Augmentation Core Facility.

Today, Herrin is the lead clinician in Georgia Tech’s exoskeleton and prosthetics studies and fosters meaningful connections with the patient community who participate in studies, providing critical data and feedback that propel the work forward.

“I think the biggest and most interesting part of what I do revolves around patients. They are my big why,” she said. “I also love writing about problems that clinicians and patients are facing — and figuring out how we solve those in practical ways. I want the work we do to actually make it to people, whether that’s the patient or the clinician. That’s been the focus of everything I’ve ever done.”

One of Herrin’s first projects in her current role involved writing a grant about microprocessor prosthetic knees and how to guide their use in clinical practice. She was awarded the grant, led the study, and now her work is out in the real world in the form of an app that guides clinicians in determining the right microprocessor prosthetic knee for their patients.

Herrin brings clinical wisdom to the robotics and prosthetics teams, helping ensure that devices are safe, comfortable, and appealing for real people. She is constantly inspired by the people who give their time to the research. Many of them have dealt with serious challenges, including amputations, strokes, and other conditions.

She also mentors students on how to interact respectfully and empathetically with participants, always grounding the work in human experience.

“I really try to engage with the communities we serve,” Herrin said. “I don’t want it to feel transactional. I want people to know they’re part of our team, beyond just participating in a study.”

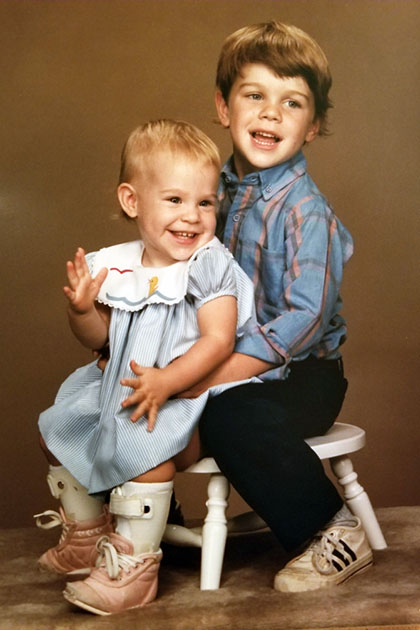

Starting at a very young age, Herrin wore braces to address nerve damage in her legs.

Her journey gives her a deep empathy for the people she meets in the lab. “My own experience with mobility challenges as a kid gives me a special understanding,” she said. “It all feels relatable and personal to me — especially the projects that help kids walk.”

That’s one reason she’s drawn to wearable robotics research, like exoskeletons that can help children move more naturally without standing out.

“The idea that we can make something a kid can use to walk better without feeling stigmatized — that speaks to my soul,” Herrin said.

As a child, Herrin remembers looking down at her leg braces and deciding she was done with them. “I quit wearing my braces for social reasons,” she said. “When I got to middle school, I just didn’t like them anymore.”

Years later, as a researcher reviewing survey feedback from an exoskeleton study, she came across a participant’s comment suggesting that wearable devices should be invisible.

“I feel like that’s my new mantra,” Herrin said. “OK, maybe they won’t be truly invisible. But I want them to be wearable and not hugely noticeable — something that doesn’t make you look like you have a ‘problem.’ I’d rather have you look and feel confident like the next Iron Man.”

That’s exactly what she’s helping build — technology that restores mobility and confidence.

“Beyond the publications and the prototypes, what I really want is to see our devices on patients,” Herrin said. “Helping them move better, go farther, carry their grandkids, or just get out of the house. That’s the real success.”

Writer and Media Contact: Catherine Barzler, Research Writer/Editor Sr., Institute Communications | catherine.barzler@gatech.edu

Videos: Christopher McKenney, Video Producer, Research Creative Services

Photos: Christopher McKenney and courtesy of Kinsey Herrin

Series Design: Daniel Mableton, Senior Graphic Designer, Research Creative Services

About the College of Engineering (CoE)

The Georgia Tech College of Engineering is creating tomorrow’s leaders in engineering, science and technology. It offers internationally renowned programs, giving students opportunities for research and real-world experience. Engineering offers more than 50 different degree tracks at the bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral levels, and its schools are consistently ranked among U.S. News & World Report’s top 10. As part of a public university, the College of Engineering remains an excellent value for an elite education.

Learn More

To explore careers in research, visit the Georgia Tech Careers website. To learn more about life as a research scientist at Georgia Tech, visit our guide to Research Resources or explore the Prospective Faculty hub on the Office of the Vice Provost for Faculty website.