This Eighth Grader Is Shaping the Future of Wearable Robotics

How a middle schooler with cerebral palsy became a vital contributor to Georgia Tech’s cutting-edge robotic exoskeleton research — offering data, feedback, and a passion for innovation.

Case Neel, 13, is a busy kid who loves coding and robotics, captains his school’s quiz bowl team, and lives with his family on a farm northwest of Atlanta.

He also has cerebral palsy — and for the past four years, he has played a key role in improving one of the most exciting medical devices at Georgia Tech.

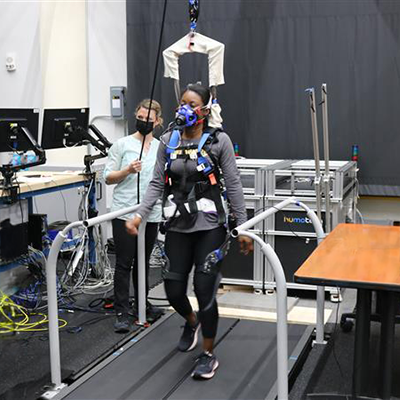

“My role here is as a participant in exoskeleton research studies,” Case explained. “When I come in, researchers hook me up to sensors that monitor my gait when I’m walking in the device, and then they get a whole lot of data based off that.”

Case is part of a vibrant community of Georgians with disabilities who donate their time and energy to help Georgia Tech researchers improve wearable robotic devices.

Like many people with cerebral palsy, Case walks with impaired knee movement. Georgia Tech’s pediatric knee exoskeleton is designed to help children and adolescents walk with increased stability and mobility. Case’s data enables the researchers to analyze the exoskeleton’s performance.

Kinsey Herrin, principal research scientist in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, leads exoskeleton and prosthetic studies and fosters meaningful connections with the participant community.

“Case and others’ participation in our exoskeleton studies is so critical for moving our devices forward,” Herrin said. “The big picture of our research is to make these wearable robotics so they help people beyond the lab — extending into healthcare settings and everyday life in their community.”

In addition to the physical device tests, she said, “We’re always asking our participants about their experiences and how we can make our devices work better for them.”

Case is known for his intellectual engagement and precise suggestions for the exoskeleton.

“I know all of the different muscles, so I can give the researchers very accurate feedback on what needs to be adjusted,” he said.

“This exoskeleton is light years ahead of anything else on the market. I think it would be really cool to say that I was one of the first testers while it was still in the development phase.”

Erin, Case’s mother, started taking Case to different types of therapy for his cerebral palsy when he was a baby. Because he made so much progress as a young child, his need for intensive clinical therapies decreased over time.

“The timing of us coming to Georgia Tech was a great bridge from clinical therapy to a different type of activity for him,” Erin said. “Case is interested in the technology, and he sees how his data benefits the research. It is an activity that helps him improve and strengthen his gait, even when he’s not wearing the exoskeleton.”

Case’s doctor also strongly encourages Case and Erin to keep going back to Georgia Tech to participate in the studies.

“I think Case feels honored to be a part of this,” Erin added. “He shares with his friends at school, and it’s something he is proud of, something he has worked hard for.”

While Case already loved computers before joining the research studies, his participation has broadened his appreciation of data and coding.

“I love seeing the code and how everything looks with the motion capture,” Case said. “I’ve also learned about the programming language Python, user interfaces, and system architecture, and have applied those to my own projects. Coming here has really helped me.”

When Case first joined the studies as a third grader, the pediatric exoskeleton was made of heavy stainless steel. Now, it’s made of light carbon fiber and paired with a biofeedback video game that nudges participants to correct their gait in real time.

Case plans to return to Georgia Tech to test new versions of the device.

“This exoskeleton is light years ahead of anything else on the market, and that’s why this research is really important,” he explained. “Without these studies, you can’t find issues with the exoskeleton, and if you can’t find the issues, you’re going to have a buggy product.”

Throughout the process, Case acknowledges how rare it is for a young teenager to have such a significant role in university research.

“I hope that the exoskeleton will go to market one day,” he said. “I think it would be really cool to say that I was one of the first testers while it was still in the development phase.”

Georgia Tech: Research for Real Life

Case isn’t a subject of research — he’s a partner in it. Like many Georgians, he teams up with our engineers to create technology that helps people move, heal, and thrive.

For Case, that means showing researchers how cerebral palsy changes movement and how technology can support each step forward.

At Georgia Tech, real-life experiences are the heart of our discoveries.

Nathan Wallace Takes Steps to Advance Prosthetics

Nathan Wallace Takes Steps to Advance Prosthetics  The Robotic Breakthrough That Could Help Stroke Survivors Reclaim Their Stride

The Robotic Breakthrough That Could Help Stroke Survivors Reclaim Their Stride  No Matter the Task, This New Exoskeleton AI Controller Can Handle It

No Matter the Task, This New Exoskeleton AI Controller Can Handle It  Universal Controller Could Push Robotic Prostheses, Exoskeletons Into Real-World Use

Universal Controller Could Push Robotic Prostheses, Exoskeletons Into Real-World Use  40 Under 40 Spotlight: Kinsey Herrin

40 Under 40 Spotlight: Kinsey Herrin  The Perfect Fit: Crafting a Career at the Intersection of Making, Helping, and Human Mobility

The Perfect Fit: Crafting a Career at the Intersection of Making, Helping, and Human Mobility