Nuclear Waste: What It Is — and What It Isn’t

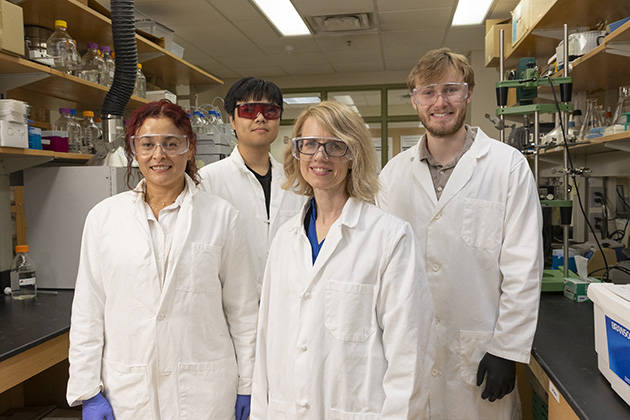

Martha Grover, professor in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, with her research team. [Photo by Christopher McKenney]

Thanks in large part to science fiction movies and TV, the term “nuclear waste” can be alarming — calling to mind images of glowing green goo oozing into the soil and contaminating all it touches. These visuals paint a picture of an environment made unlivable for humans, animals, and all living organisms.

Reality is far less dramatic. According to Georgia Tech nuclear experts, nuclear energy is, like other fuel sources, safe to use when proper procedures are followed. It is also a cleaner alternative to fossil fuels, as it produces no harmful emissions.

“Nuclear waste is often perceived as immediately lethal, but exposure risks are managed with proper safety protocols,” explained Martha Grover, professor and Thomas A. Fanning Chair in Equity Centered Engineering in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at Georgia Tech.

She adds that radiation isn’t unusual.

“People don’t realize that common items such as bananas and smoke detectors contain radioactive elements. Radiation is everywhere and is not always dangerous.”

“Nuclear waste is often perceived as immediately lethal, but exposure risks are managed with proper safety protocols.” —Martha Grover

So, what is nuclear waste?

Spent nuclear fuel containers at a nuclear plant site [Photo courtesy of DOE Office of Nuclear Energy]

To produce nuclear power, radioactive fuel is placed inside a nuclear power plant’s reactor, where it undergoes a controlled chain reaction. This makes the fuel highly radioactive and releases heat, which is converted into electricity. When the fuel can no longer sustain the reaction efficiently, it is removed and classified as nuclear waste.

Nuclear power plants in the U.S. have an open nuclear fuel cycle, meaning spent fuel rods are stored rather than recycled. After cooling in spent fuel water pools at the plant, the fuel is moved to dry storage in secure casks, where it slowly loses radioactivity. Eventually, spent fuel may be placed in deep underground facilities designed to safely contain it for hundreds of years, until it loses most or all of its radioactivity.

Beyond power plants, the U.S. also manages legacy nuclear waste from Cold War weapons programs. Stored at multiple sites across the country, this material falls under the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Legacy Management.

At these sites, scientists separate highly radioactive materials from the liquid waste. The remaining liquid is then converted into a solid form for safer long-term storage. Georgia Tech researchers work closely with DOE labs to make the cleanup process safer and more efficient.

Grover’s lab is developing cutting-edge technologies to identify the different radioactive materials contained in the legacy waste.

“We’re developing real-time inline monitoring to remotely identify materials within the waste,” said Grover. “This could dramatically speed up its processing and improve safety at the same time.”

“Every energy source has trade-offs. But nuclear waste, when managed scientifically, is far less problematic than the billions of tons of CO₂ and other greenhouse gases and pollutants that we release every year by burning fossil fuels.” –Bojan Petrovic

As nuclear power use expands, what will happen to the spent fuel?

Bojan Petrovik, professor of nuclear engineering in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering [Photo courtesy of Georgia Tech]

Civilian and weapons-related nuclear programs are strictly separated. The civilian nuclear waste generated from U.S. power plants so far can be entirely contained in an area the size of a football field, stacked to a height of about 10 yards.

Bojan Petrovic, professor of nuclear engineering in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, noted, “Every energy source has trade-offs. But nuclear waste, when managed scientifically, is far less problematic than the billions of tons of CO2 and other greenhouse gases and pollutants that we release every year by burning fossil fuels.”

At plant sites, spent nuclear fuel is handled with utmost care, and the risk of leakage or contamination is minuscule. The casks storing spent fuel rods are built to withstand natural disasters and human-created threats.

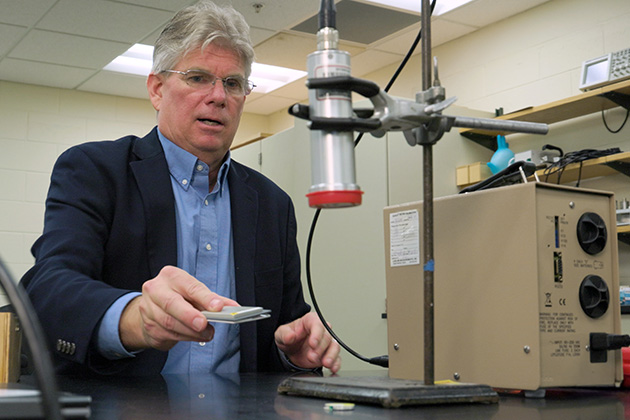

Steve Biegalski, chair of nuclear and radiological engineering and medical physics program [Photo by Christopher McKenney]

“Spent fuel stored on-site at nuclear facilities is under the same security as the reactors themselves,” explained Anna Erickson, professor of nuclear engineering in the Woodruff School. “You could stand next to a spent fuel cask and not worry.”

While the U.S. stores its spent fuel, countries like France and Japan recycle theirs in what’s called a closed cycle — reprocessing used fuel for reuse.

Past U.S. policy has limited the reactor fleet’s ability to recycle fuel, even though it is technically possible. But future nuclear technologies are being designed to support a closed fuel cycle.

Steve Biegalski, chair of Georgia Tech’s nuclear and radiological engineering program in the Woodruff School, researches the design of advanced nuclear reactor systems.

“We won’t be generating more waste — we’re going to generate less. Advanced reactors will use fuel more efficiently and reduce waste volume significantly,” he explained.

“Spent fuel stored onsite at nuclear facilities is under the same security as the reactors themselves. You could stand next to a spent fuel cask and not worry.” —Anna Erickson

Beyond reducing waste, researchers are exploring ways to turn spent fuel into something valuable.

From left to right: Henry La Pierre, Anna Erickson, Martha Grover [Photo by Jess Hunt-Ralston]

“Spent nuclear fuel isn’t just waste; it’s an opportunity,” said Biegalski. “We can repurpose it for new reactors, long-lasting batteries, and even medical treatments. Imagine a double-A battery that lasts 100 years. That’s the kind of innovation nuclear waste can enable. It sounds wild, but it’s real.”

Startups are already turning nuclear byproducts into breakthroughs, powering advanced medical imaging procedures, remote military operations that require long-lasting power, disaster relief zones lacking infrastructure, and even space missions. Their high energy density makes nuclear byproducts ideal for lunar or Martian bases.

While these applications show what’s possible today, researchers like Henry La Pierre are laying the scientific groundwork for tomorrow. La Pierre, a professor in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry, studies the chemical and physical properties of long-lived isotopes of neptunium, plutonium, and americium. Understanding the fundamental chemistry of these critical components of spent nuclear fuel opens new avenues for closed-cycle fuel reuse, separation of valuable isotopes, and management of legacy nuclear materials.

“While technical applications of the human-made elements beyond uranium (the transuranic elements) have been in development since the 1940s, the understanding of the chemical properties of these elements is still developing and is urgently needed to address contemporary challenges in nuclear energy and nuclear security,” said La Pierre.

“Spent nuclear fuel isn’t just waste; it’s an opportunity. We can repurpose it for new reactors, long-lasting batteries, and even medical treatments. Imagine an AA battery that lasts 100 years. That’s the kind of innovation nuclear waste can enable. It sounds wild, but it’s real.” —Steve Biegalski

Why does nuclear waste handling matter to the public?

Managing nuclear waste safely protects our health and the environment. A recent executive order is pushing for smarter nuclear energy — meeting power needs while cutting waste through better fuel use and recycling.

The U.S. government keeps tight control over nuclear materials: DOE handles storage, the EPA checks environmental safety, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission sets strict rules to keep communities safe.

The good news? We already have the technology to recycle and store nuclear waste securely. What’s needed now is strong policy and public awareness, because informed citizens help ensure that these solutions are put into action.

Writer: Priya Devarajan

Media Contact: Shelley Wunder-Smith | shelley.wunder-smith@research.gatech.edu

Videos: Christopher McKenney

Photos: Christopher McKenney, Jess Hunt-Ralston, and Courtesy of Georgia Tech and National Agencies

Copy Editors: Shelley Wunder-Smith and Stacy Braukman

Georgia Tech’s Role in Tackling Nuclear Waste

Steve Biegalski leads research on advanced nuclear reactor designs that use fuel more efficiently and will reduce waste. In particular, he has helped design and license the Natura Resources advanced molten salt reactor that will be built at Abilene Christian University — the first of its kind in the U.S. The university received Nuclear Regulatory Commission construction permission in September 2024, marking the first such permit in over 40 years.

Anna Erickson researches nuclear nonproliferation and reactor safety, focusing on new reactor designs and technologies that reduce the risk of nuclear materials being misused, while also improving ways to monitor and protect nuclear facilities. She combines engineering with innovative detection methods to support clean energy and global security.

Martha Grover collaborates with the Savannah River National Laboratory to identify elements in legacy nuclear waste for faster processing. Using machine learning and data science, her team develops tailored algorithms that use sensor data to estimate and identify the composition of radioactive and other elements in the waste material.

Henry La Pierre studies long-lived isotopes of plutonium and neptunium. As director of the Transuranic Chemistry Center of Research Excellence, a national research center funded by the National Nuclear Security Administration, La Pierre leads national efforts to understand these materials and strengthen national security.

Bojan Petrovic designs next-generation nuclear reactors and fuel cycles that will reduce the amount and toxicity of nuclear power waste. By developing systems that can reuse or transform spent fuel, Petrovic’s work aims to make nuclear energy cleaner, safer, and more sustainable.

Breaking Down Nuclear Waste

To understand why nuclear waste isn’t always as dangerous as people think, it helps to know the two main types:

- Low-level waste: Contaminated items like lab coats and gloves from plant operations with low, short-lived radioactivity and plant parts and tools that stay radioactive for about 100 years.

- High-level waste: Spent nuclear fuel and waste products after spent fuel reprocessing that remain radioactive for thousands of years.

Low-level waste is typically stored in underground facilities designed and developed specifically to store it in the U.S. and globally.

High-level waste from Cold War programs (legacy waste) and nuclear power plants requires special handling by the Department of Energy, which is pursuing all options — including a consent-based approach with communities to find permanent storage sites.

High-level nuclear waste stored at Nuclear Plant Sites [Photo courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy]

Transuranic waste stored at DOE WIPP Plant in Carlsbad, New Mexico [Photo courtesy of WIPP Video]