Georgia Tech Plugged Him In. Now He’s Wired for Problem-Solving

Scott Gilliland’s winding path led to breakthroughs in wearable tech that solve challenges for people with Parkinson’s and help us understand dolphin communication.

Wearing a refined CHAT prototype, Scott Gilliland showcases the kind of tech that turns bold ideas into real-world tools. His work with Georgia Tech’s Institute for People and Technology brings together creativity, research, and purpose.

A research team in the Atlantic Ocean listens to dolphins, testing technology that may one day decode their communication system. Thousands of miles away, a Parkinson’s patient may speak more clearly, thanks to a device that helps them overcome speech challenges caused by the condition. One sounds like science fiction; the other is a transformative medical breakthrough. Yet both are rooted in the same field of research: ubiquitous computing.

Scott Gilliland, a senior research scientist at Georgia Tech’s Institute for People and Technology (IPaT), has played a key role in developing these technologies. IPaT connects researchers across disciplines to turn innovative ideas into practical applications. It’s a natural fit for Gilliland, whose work blends human-centered design with embedded systems, which are small computers built into everyday devices to perform specific tasks.

As a researcher, he often partners with colleagues in the College of Computing, where he also earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees. His work in ubiquitous computing and wearable systems is quietly reshaping how we interact with the world.

“Ubiquitous computing” refers to technology that is embedded in everyday objects and environments — for example, clothing. It makes computing power accessible without being intrusive. Gilliland’s projects span different fields of study that aim for the same goal: real-world benefit through innovative, human-centered technology.

He sees his role as connecting dots between disciplines to make technology more accessible.

“Human-computer interaction is a little bit of public policy and a little bit of psychology, but basically it’s where technology meets people,” Gilliland said. “A lot of the work is figuring out how people interact with technology and then figuring out what value is provided back to them.”

Finding His Path at Georgia Tech

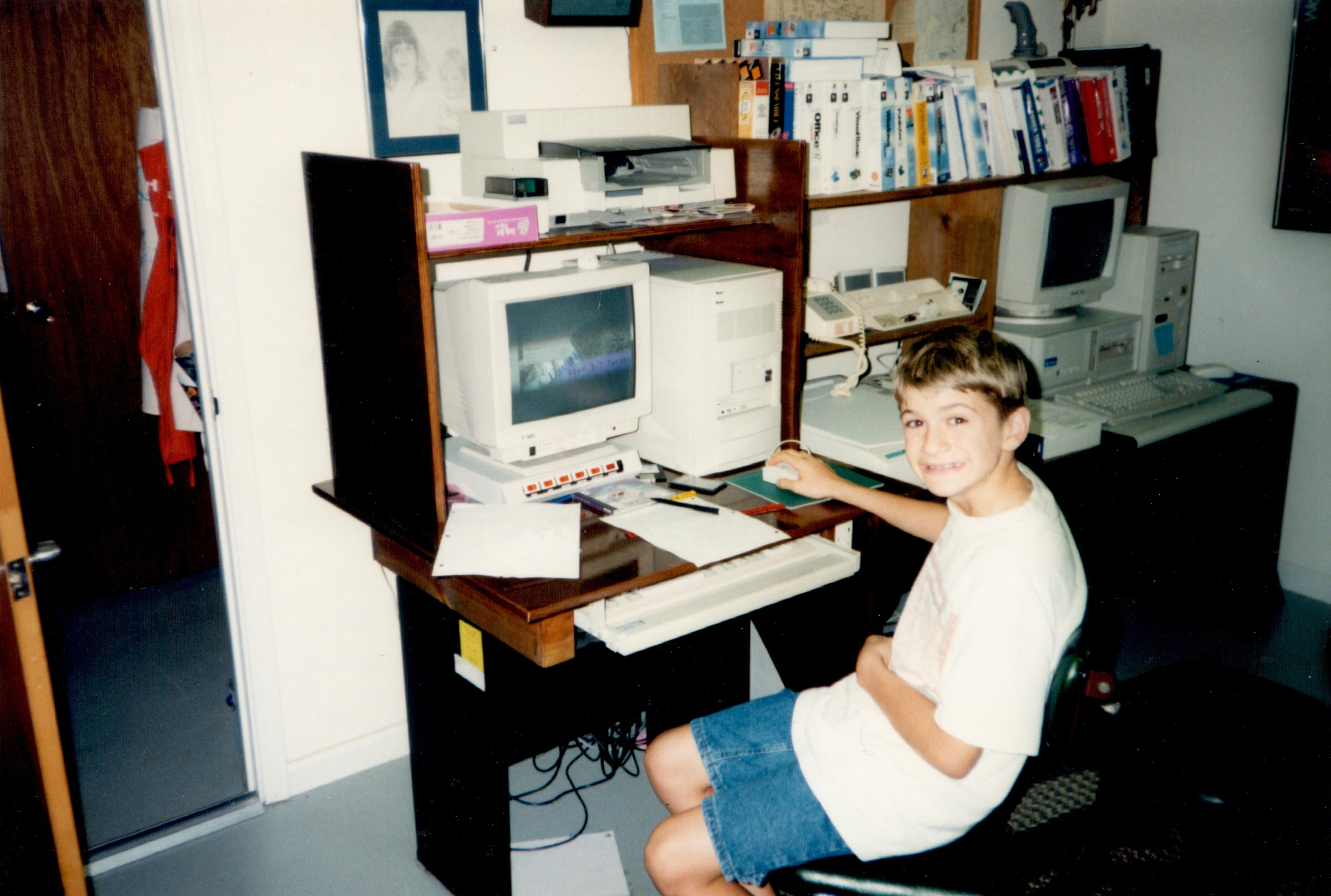

Long before his career in wearable tech, Gilliland (age 13) was a curious child growing up in Peachtree Corners, Georgia.

Growing up in Peachtree Corners, Georgia, Scott Gilliland didn’t exactly picture himself thriving in college.

“If you were to ask my mom when I was 10 about what I’d be doing today, she’d be surprised I am as social and well-spoken as I am,” he said. “I was the kid who did well in the math and physics classes but struggled through language arts and history.”

He admits he didn’t take his high school computer networking classes very seriously.

“Those classes were basically just an excuse to mess around with computers and somehow get credit for it,” he recalled. He enrolled at Georgia Tech in 2004 after graduating from Norcross High School; even then, he didn’t see himself as a well-rounded student.

Gilliland was initially undecided about his major. He arrived at Tech leaning toward electrical engineering, but an early seminar planted the seed that ultimately led him to computer science.

“When I first got to Georgia Tech, they had this class to help increase undergrad retention. It was a study skills course that prepared incoming high schoolers for the work they’ll do at Tech. The College of Computing had their own version: a one-hour-a-week seminar, and my professor was Thad Starner, who did wearable computing research.”

As Gilliland progressed in his undergraduate studies and considered elective courses, one class called “Mobile and Ubiquitous Computing” caught his eye. A familiar name was listed as the professor.

“I had blank spots on my schedule and wondered what I was going to take,” Gilliland said. “As I was scrolling through classes, I saw the name Thad Starner, and I thought, ‘That’s the guy who did the seminar class three years ago. I’ll sign up for this.’”

Gilliland often uses a sewing machine to integrate embedded technology into wearable prototypes.

That course with Starner was the moment Gilliland truly plugged into his interests. From there, his path into research began to take shape. Though Gilliland was one of only two undergrads in the master’s-level course, his final project — involving 3D printing and laser cutting — caught his professor’s eye.

“Starner thought highly of the project, and afterward, he asked if I wanted to stick around and try to solve more wacky problems for undergrad research projects,” said Gilliland. “So, I showed up in his lab and kept doing research for credit every semester until I graduated. Then he talked me into staying for a master’s degree.”

Gilliland decided not to pursue a Ph.D. when he realized how much he liked focusing on projects. Research became more exciting to him than the specialized path of doctoral study. “I’ve thought about doing it — never got around to it — and probably never will,” he said.

The corporate route didn’t appeal to him either.

“I’m good at making the first, second, and third prototypes,” he explained. “I’m not the right person to help get something manufactured in the hundreds of thousands. If you need someone to sit down and do nothing but program Android apps all day, why would you want somebody who has other skills too?”

For Gilliland, research faculty life offers the best of both worlds: the freedom to explore new ideas and the chance to build things that don’t exist yet.

Designing Tech That Makes a Difference

Gilliland is pictured at the IPaT Craft Lab in Georgia Tech’s Technology Square Research Building, where his work in embedded systems and human-centered design continues to shape real-world innovation.

Thinking big, solving “wacky” problems, and diving into new subject matter define Gilliland’s approach.

He is skilled at reverse engineering concepts that don’t quite work until they are transformed into technology that bridges the gap between research and real-world usage. His expertise in wearable computing and embedded systems makes him a go-to problem solver. Often, researchers come to him with rough versions of embedded technologies that are too clunky or not quite functional, and he works backward to find what’s missing.

“The projects I work on usually require three elements,” he said. “First, they involve electronic hardware design, which means creating circuit boards. Then, they require writing software that runs on the tiny computers embedded in those boards. And finally, they typically include some form of 3D printing or manufacturing to build physical models — to test how they can be worn on the body or deployed in the real world.”

One example is a recent collaboration between David Anderson, a professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering; Meredith Caveney, a Ph.D. student in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering; and Dr. Amanda Gillespie and Dr. Adam Klein of Emory University Hospital. Together, they developed the Speech-Assisting Multi-Microphone System (SAMMS), a wearable feedback tool designed to help Parkinson’s patients adjust their speech volume. People with Parkinson’s often speak too softly without realizing it, and this device alerts them to increase their vocal effort. The concept was promising, but the prototype wasn’t wearable enough because it was too boxy to comfortably fit around a human head.

“When they happened upon the Institute for People and Technology and brought their challenge to us, a co-worker and I redesigned the circuit board and reworked the 3D-printed form,” he said.

It took Gilliland and his co-workers about three months to solve the problem and make the device feasible for real-world use. It is now in use in in-home clinical trials.

Taking Wearable Technology to the Open Ocean

Gilliland and Denise Herzing of the Wild Dolphin Project work in the Atlantic Ocean on a project using wearable technology to study human-dolphin interaction.

Some solutions are found quickly, and some require time and many iterations.

One pursuit that has made waves in Gilliland’s career is the Wild Dolphin Project, a longtime collaboration. Though Gilliland didn’t originate the initiative, he and Starner have made significant contributions since joining in the early 2010s.

The Wild Dolphin Project, founded by Florida Atlantic University’s Denise Herzing, promotes dolphin conservation by studying wild dolphins without touching or disturbing them. This lets scientists observe how dolphins naturally live and communicate. The team shares their findings to help others care about dolphins and the ocean, and why protecting them matters.

Herzing felt she needed a way to play sounds to dolphins underwater and record their responses at the high frequencies dolphins vocalize. That led to the creation of the C.H.A.T. device (Cetacean Hearing Augmentation Telemetry), a wearable underwater computer used by researchers to attempt two-way communication between humans and dolphins. Starner helped lead the device’s development, and Gilliland played a key role in designing and refining the hardware by making it more functional, wearable, and field-ready.

The latest version caught Google’s attention and was showcased at this year’s Google I/O Developer Conference. The momentum also helped spark the development of DolphinGemma, an artificial intelligence (AI) model that uses machine learning to help researchers better understand dolphin communication patterns.

“It’s a really cool project where we try to understand the language abilities of a species that we don’t really know a ton about,” said Gilliland. “You’re getting to do it with weird hardware, in cool places, and sometimes you get to go out on a boat in the Bahamas.”

Turning Research Into Real-World Solutions

Gilliland is shown on a research vessel wearing an early prototype designed for underwater communication.

Gilliland wasn’t an expert on Parkinson’s or dolphins when he joined those projects, but he ended up learning a lot about both subjects. That happens with each new project he tackles — he dives deeply into the subject matter before addressing the technical problems.

The knowledge he gains in one area often fuels innovation in another. Gilliland’s work spans disciplines, but it’s united by a common thread: improving the human condition. Gilliland’s research has led to technology that supports coastal communities by monitoring sea levels and even contributed to improving rocket fuel systems for spacecraft.

“When I dive into a new field, I often bring in the latest and greatest technology from five different projects that end up overlapping,” Gilliland explained. “Thinking outside the box and coming up with unique technical solutions applies to research taking place all over Georgia Tech.”

For Gilliland, the work isn’t just about solving problems. It’s about exploring possibilities — and following wherever that unexpected path may lead.

Writer and Media Contact: Julian Hills, Executive Communications Specialist, Executive Communications | julian.hills@gatech.edu

Videos: Christopher McKenney, Video Producer, Research Creative Services and courtesy of the College of Computing at Georgia Tech

Photos: Christopher McKenney and courtesy of Scott Gilliland

Series Design: Daniel Mableton, Senior Graphic Designer, Research Creative Services

About the Institute for People and Technology (IPaT)

The Institute for People and Technology (IPaT) is an Interdisciplinary Research Institute at Georgia Tech offering a unique people-first approach to research and innovation. IPaT assembles academics, industry, government, civil society, and other partners to create people-centered solutions to some of society’s thorniest challenges.

IPaT focuses on real-world impact, translating research out of the lab and into people’s lives in the form of real products, applications, and community education and programming. Learn more.

Learn More

To explore careers in research, visit the Georgia Tech Careers website. To learn more about life as a research scientist at Georgia Tech, visit our guide to Research Resources or explore the Prospective Faculty hub on the Office of the Vice Provost for Faculty website.