Georgia Tech Uses Computing and Engineering Methods to Shift Neuroscience Paradigms

Meet Georgia Tech’s computation and cognition experts.

A neuron is more than just a neuron. These cells, found throughout the nervous system and the brain, work together in circuits that perform the complex calculations needed for our perception, memory, behavior, and cognition.

This means that breakthroughs in neuroscience don't just rely on biology or medical knowledge, but also on the quantitative skills needed to understand and model these circuits. Faculty at Georgia Tech use their expertise in engineering, math, and computer science to apply common principles of these disciplines to neuroscience research. Within the Institute for Neuroscience, Neurotechnology, and Society (INNS), neuroscientists use these quantitative methods to understand how humans think, treat disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, and better understand psychiatric disorders.

MODELS: Using Math to Understand the Brain

Hannah Choi has always been interested in applied mathematics. Little did she know that when she started graduate school, the most compelling math equation would be the brain.

“I got really interested in nonlinear dynamical systems — where the output is disproportionate and unpredictable from the input — and then I realized the brain is actually one of the most complicated and interesting nonlinear dynamical systems,” recalled Choi, an assistant professor in the School of Mathematics.

Learning how the brain computes, or processes, information is her goal. Choi collaborates with experimental neuroscientists to turn their data into mathematical models. From there, Choi can use these models to improve computing, like neuromorphic computing strategies or artificial neural networks.

One example of how Choi turns neuroscience data into models is by following the spiking patterns of a large neuronal network. When a neuron fires, the activity can be represented as a spike. These spiking patterns change depending on how they’re connected to other neurons — in other words, a dynamical system. Each spike can be quantified.

Choi isn’t only trying to build better neural networks; she also hopes to determine how the brain functions at a fundamental level. With this information, scientists can better treat diseases. Patients with Alzheimer’s, for instance, have different connectivity patterns between different brain regions than healthy patients.

“Understanding how different brain regions are wired together can actually help us study different diseases and what causes certain cognitive defects,” said Choi, whose research is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, and the Sloan Foundation.

“I got really interested in nonlinear dynamical systems — where the output is disproportionate and unpredictable from the input — and then I realized the brain is actually one of the most complicated and interesting nonlinear dynamical systems.” —Hannah Choi

METACOGNITION: Building Models to Learn How We Think

Dobromir Rahnev’s research in the Computations of Subjective Perception Lab focuses on metacognition. [Photo by Rob Felt]

How individual people see the world is not the same. From color blindness to neurological disorders, perception is a moving target. This is why it’s so important for neuroscience researchers to understand how and why we perceive.

To help a mentally ill or cognitively declining brain, we need to know how a healthy one works. Thinking about how we think, or metacognition, is a vital part of this. The research Dobromir Rahnev conducts in the Computations of Subjective Perception Lab focuses on metacognition. Funded by NIH, the School of Psychology professor studies how the brain monitors and controls its own activity — in other words, how humans introspect and mentally course-correct during a task. Rahnev builds computational models of these underlying metacognition structures.

His research group asks people to perform tasks while inside an MRI machine. These tasks are often perceptual. The researchers provide a stimulus; the study participant then gives a rating reflecting their confidence in their perception’s correctness.

For example, the researchers might show a visually distorted number between 0 and 9. The distortion affects the participant’s certainty about what the number is. With the fMRI, Rahnev can see which part of the brain activates when a person is confident that what they are observing is correct. From this data, the researchers can build computational models on how confident a person is after seeing different stimuli.

The implications of Rahnev’s research go beyond the lab. Many psychiatric disorders involve people being overconfident that their hallucinations are real.

“We know metacognition is important in many mental disorders, but we don't know why,” Rahnev said. “It’s hard to understand the psychiatric mechanisms when we don't even fully understand how the mechanisms are computed. So, my lab works on the very basic science of this.”

Rahnev hopes that once they discover the basic mechanisms of how confidence works in healthy brains, they can then see what goes wrong in disease — from how the brain processes thoughts to the affected brain region. With this knowledge unlocked, treatments could improve for those managing challenging psychiatric disorders.

NAVIGATION: Determining Neurodegenerative Disease Through Movement

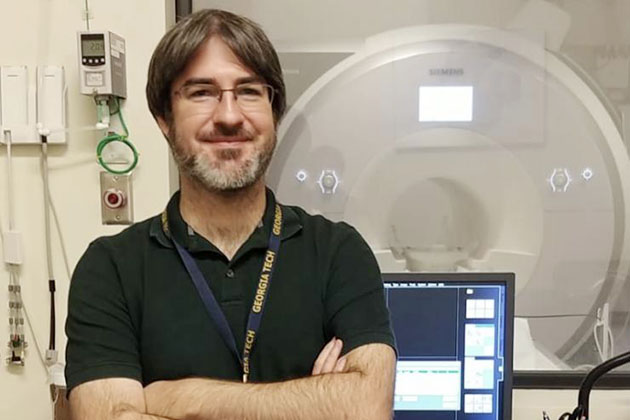

Thackery Brown at Georgia Tech's Center for Advanced Brain Imaging. [Photo courtesy of Thackery Brown]

When navigating a room, no two people will move through it in the same way. This concept, spatial navigation, is more than a matter of geography. It’s also a fundamental problem in many neurodegenerative diseases. One of the earliest and most significant symptoms of Alzheimer's disease is spatial disorientation and getting lost.

“Spatial navigation issues apply to so many disorders,” noted Thackery Brown, an associate professor in the School of Psychology. “So many disorders affect perception, and we need perception, as well as memory, to navigate.”

In Brown’s research, he presents healthy people with navigation problems in virtual reality. Using fMRI, the researchers can see what parts of the brain light up as a person works their way through an environment. They take this neuroimaging data and run it through machine learning algorithms. These algorithms look for patterns that can be decoded for what people remember or think about in order to navigate. The work is supported by the NIH and the Shurl and Kay Curci Foundation.

“We can see what a person's brain looks like when they are paying attention to a certain landmark, for example,” Brown said. “Then we can have the machine learning algorithm ‘listen’ to the brain and ask when it is thinking about this landmark. This sort of mind-reading tool that machine learning presents is really powerful — it can give us a window into how people think.”

From neuroimaging, the researchers can determine how these patterns change with Alzheimer’s or other disorders — or even just stress. Brown would eventually like to have these types of machine learning algorithms monitor and respond to data in real time. This would enable feedback or neural interventions to be delivered and help people with diseases make better navigational decisions in the moment.

“Spatial navigation issues apply to so many disorders. So many disorders affect perception, and we need perception, as well as memory, to navigate.” —Thackery Brown

CIRCUITS: Applying Engineering to Neuro Assistive Devices

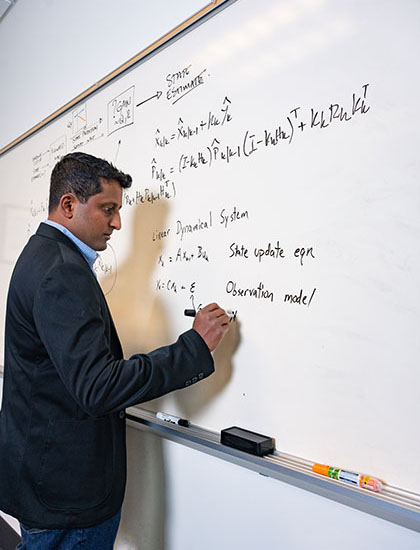

Chethan Pandarinath brings his expertise in electrical and computer engineering and physics to neurodegenerative diseases. [Photo by Joya Chapman]

Chethan Pandarinath planned for a career in electrical engineering, but when he was in graduate school, his father’s Parkinson’s disease started to have debilitating effects. Pandarinath saw firsthand how neurodegenerative diseases affect people. Often, people with Parkinson’s are treated with implanted electrodes that can stimulate the brain with current, a procedure called deep-brain stimulation.

“When my father went through this, I saw that even though we may not know much about the brain’s complexity, simple engineering principles can go a long way to improving the quality of life for people with these disorders,” said Pandarinath, an associate professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering.

He realized he could bring his expertise in electrical and computer engineering and physics to neurodegenerative diseases. The brain is made of billions of neurons, and principles from engineering can help conceive of those neurons as a circuit carrying information, such as our intention to move or speak. Now he builds assistive devices that tap into these circuits to potentially help patients with partial paralysis from stroke, ALS, or spinal cord injuries.

“When the brain has effectively been disconnected from the body, our goal is to build devices that interface with the brain directly,” Pandarinath said. “So, when somebody thinks about an action, we can help them perform it, whether it's controlling a computer or moving a robotic arm.”

The researchers work with people across Atlanta as well as the U.S. One local collaborator experienced a brainstem stroke 15 years ago. The patient had sensors implanted in their brain that the researchers can use to study the brain and develop assistive devices. These devices could restore patients' ability to communicate with loved ones.

Pandarinath’s group also collaborates with other researchers’ neuroscientific datasets and applies machine learning to them. With machine learning, the group can better parse how the data can be used to create devices that aid patients. Most of this research, whether computational or applied, is funded by the NIH.

“Most of the people we work with, their brains are effectively intact,” Pandarinath noted. “They would be capable of leading normal lives, except for their movement impairment. So, it's nice to be able to give back to that community.”

SENSES: Listening to the Brain to Better Understand Parkinson’s

The brain is made up of billions of cells that all speak their own complicated language, and Garrett Stanley wants to listen. “We'd like to have a conversation with the brain in the same way you would have a conversation with a friend,” said Stanley, a professor in the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering.

Eavesdropping on this “conversation” often requires measuring brain activity with electrodes or gene manipulation that makes neurons fluorescent and improves measurement. From this data, researchers can discover how sensory perception or decision-making functions in a neurological disease like Parkinson’s.

Although Parkinson’s is often viewed as a movement disorder, it also affects sensing, perception, and thinking. By monitoring neurons across brain regions, Stanley can determine more holistically how Parkinson’s affects the brain.

“We want to interact with and stimulate different parts of these circuits to develop intervention strategies,” explained Stanley, who also directs the McCamish Parkinson's Disease Innovation Program.

His recent research delves into the thalamus, a deep brain structure that interprets sensory inputs and helps the brain decide how to respond. He believes that understanding the thalamus and how it interacts with other brain regions could be important for understanding what breaks down in Parkinson’s patients. In the near future, Stanley won’t just be listening to the conversation — he’ll be joining it.

“Most of the people we work with, their brains are effectively intact. They would be capable of leading normal lives, except for their movement impairment. So, it's nice to be able to give back to that community.” —Chethan Pandarinath

MEMORY: Aiding Alzheimer’s Patients With Light Therapy

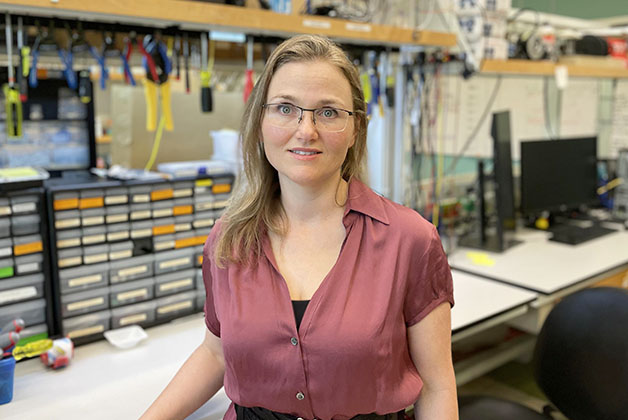

A scientist and her tools: Annabelle Singer has quantified her flicker technology with unprecedented precision in a new clinical trial. [Photo by Jerry Grillo]

Finding your way to the grocery store uses the same neural underpinnings as memories. Both navigation and memory can go wrong with diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

“We’re trying to understand how this concert of neurons works together to represent these complex experiences,” said Annabelle Singer, an associate professor in the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering. Her lab studies Alzheimer’s, and they've shown that it affects how circuits of neurons work together. They're now working to fix those circuits. The researchers look at how different patterns of stimulation can affect the brain’s immune cells and signals and use that information to develop possible therapies.

Singer’s lab works with a new therapy called sensory flicker, where lights and sounds turn on and off at specific frequencies, stimulating sensory brain regions. They've found that sensory flicker can also reach deeper cognitive circuits that affect memory, and different frequencies of stimulation alter immune signals.

“We could potentially use it as a control knob on the nervous system’s immune component, which plays a role in a lot of these diseases,” Singer said.

Writer/Media Contact: Tess Malone | tess.malone@gatech.edu

Photography: Joya Chapman, Jerry Grillo, Rob Felt, and courtesy of Thackery Brown

Copy Editor: Stacy Braukman

Computational Neuroscience Digging Deep at Georgia Tech

Computational Neuroscience Digging Deep at Georgia Tech  Flicker Stimulation Shines in Clinical Trial for Epilepsy

Flicker Stimulation Shines in Clinical Trial for Epilepsy  Head to Toe: Georgia Tech Researchers Treat the Entire Human Body Through Neuroscience Research

Head to Toe: Georgia Tech Researchers Treat the Entire Human Body Through Neuroscience Research