Nature's Time Machine: How Long-Term Studies Unlock Evolution's Secrets

Mar 19, 2025 —

A 40-year field study of Galápagos ground finches (Geospiza sp.) has provided unparalleled insights into how natural selection operates in the wild and how new species might form. (Illustration: Mark Belan/ArtSciStudios)

Georgia Tech scientists are revealing how decades-long research programs have transformed our understanding of evolution, from laboratory petri dishes to tropical islands — along the way uncovering secrets that would remain hidden in shorter studies.

Through a new review paper published in Nature, the researchers underscore how long-term studies have captured evolution's most elusive processes, including the real-time formation of new species and the emergence of biological innovations.

"Evolution isn't just about change over millions of years in fossils — it's happening all around us, right now," says James Stroud, the paper’s lead author and an Elizabeth Smithgall Watts Early Career Assistant Professor in the School of Biological Sciences at Georgia Tech. "However, to understand evolution, we need to watch it unfold in real time, often over many generations. Long-term studies allow us to do that by giving us a front-row seat to evolution in action."

The paper, “Long-term studies provide unique insights into evolution,” is the first-ever comprehensive analysis of these types of long-term evolutionary studies, and examines some of the longest-running evolutionary experiments and field studies to date, highlighting how they provide new perspectives on evolution. For example, in the Galápagos, a 40-year field study of Darwin’s finches — songbirds named after evolutionary biology’s famous founder — documented the formation of a new species through hybridization. In the lab, a study spanning 75,000 generations of bacteria showed populations unexpectedly evolving completely new metabolic abilities.

“These remarkable evolutionary events were only caught because of the long-term nature of the research programs,” Stroud says. “Even if short-term studies captured similar events, their evolutionary significance would be hard to assess without the historical context that long-term research provides.”

“The most fascinating results from long-term evolution studies are often completely unexpected — they're serendipitous discoveries that couldn't have been predicted at the start,” explains the paper’s co-author, Will Ratcliff, Sutherland Professor in the School of Biological Sciences and co-director of the Interdisciplinary Ph.D. in Quantitative Biosciences at Georgia Tech.

“While we can accelerate many aspects of scientific research today, evolution still moves at its own pace,” Ratcliff adds. “There's no technological shortcut for watching species adapt across generations.”

Decades of discovery — from labs to islands

The new paper also highlights a growing challenge in modern science: the critical importance of supporting long-term research in an academic landscape that increasingly favors quick results and short-term funding. Yet, they say, some of biology's most profound insights emerge only through multi-decadal efforts.

Those challenges and rewards are familiar to Stroud and Ratcliff, who operate their own long-term evolutionary research programs at Georgia Tech.

In South Florida, Stroud’s ‘Lizard Island’ is helping document evolution in action across the football field-sized island’s 1,000-lizard population. By studying a community of five species, his research is providing unique insights into how evolution maintains species’ differences, and how species evolve when new competitors arrive. Now operating for a decade, it is one of the world’s longest-running active evolutionary studies of its kind.

In his lab at Georgia Tech, Ratcliff studies the origin of complex life — specifically, how single-celled organisms become multicellular. His Multicellularity Long Term Evolution Experiment (MuLTEE) on snowflake yeast has run for more than 9,000 generations, with aims to continue for the next 25 years. The work has shown how key steps in the evolutionary transition from single-celled organisms to multi-celled organisms occur far more easily than previously understood.

Important work in a changing world

Stroud says that the insights from these types of studies, and this review paper, are arriving at a crucial moment. “The world is rapidly changing, which poses unprecedented challenges to Earth's biodiversity,” he explains. “It has never been more important to understand how organisms adapt to changing environments over time.”

“Long-term studies provide our best window into achieving this,” he adds. “We can document, in real time, both short-term and long-term evolutionary responses of species to changes in their environment like climate change and habitat modification."

By drawing together evolution's longest-running experiments and field studies for the first time, Stroud and Ratcliff offer key insights into studying this fundamental process, suggesting that understanding life's past — and predicting its future — requires not just advanced technology or new methods, but also the simple power of time.

Funding: The US National Institutes of Health and the NSF Division of Environmental Biology

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08597-9

A long-term field study of Californian stick insects (Timema cristinae) reveals how competing selection pressures shape their evolution. While brown-colored stick insects experience lower predation rates from Californian scrub jays (Aphelocoma californica) than their green counterparts during hot, dry years when bright green leaves are scarce, they face higher mortality due to reduced heat tolerance. This trade-off demonstrates how climate and predation simultaneously drive evolutionary adaptation in natural populations, and this case study has been used to develop statistical models that predict future evolutionary outcomes. (Illustration: Mark Belan/ArtSciStudios)

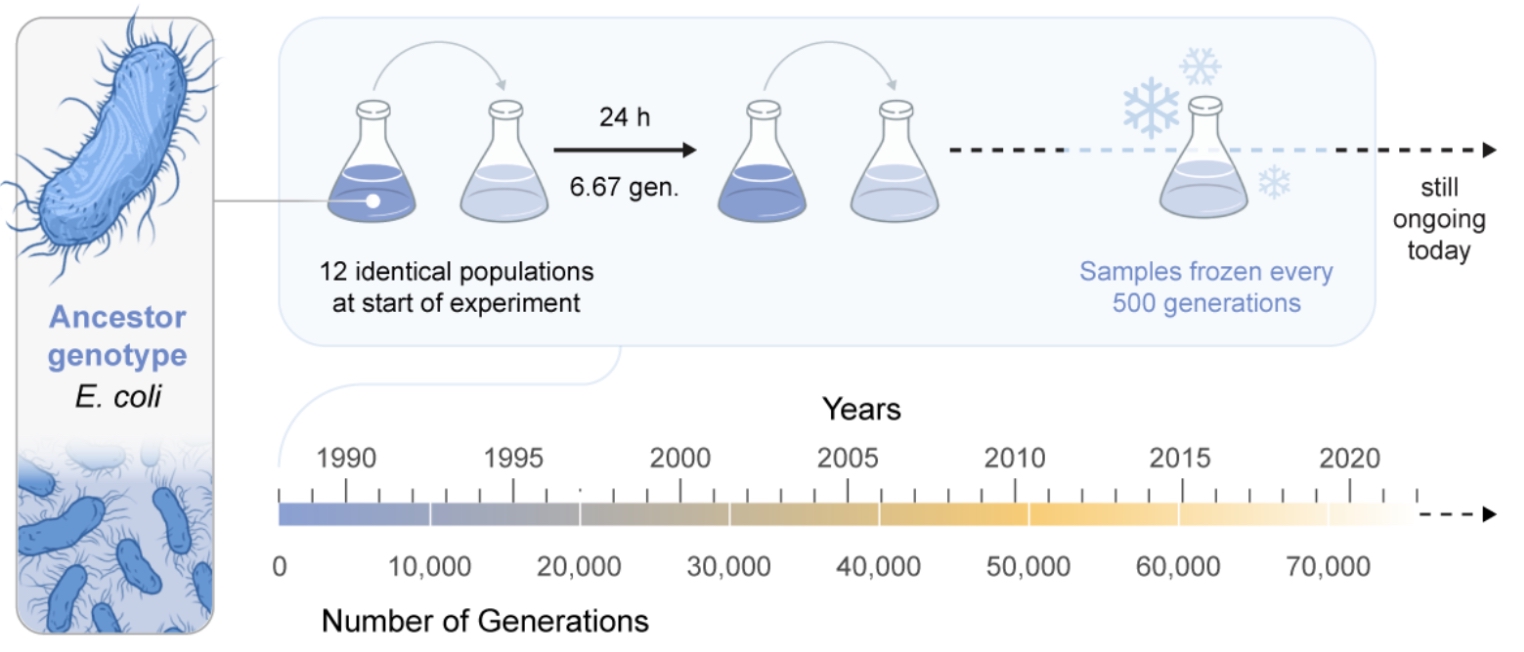

Founded in 1988, the Long-Term Evolution Experiment (LTEE) is the world’s longest-running ongoing evolution experiment now spanning 75,000 generations. Twelve genetically identical populations of the bacterium Escherichia coli have been allowed to evolve under constant conditions, and have uncovered general principles of evolutionary dynamics, such as how evolutionary novelties arise. (Illustration: Mark Belan/ArtSciStudios)

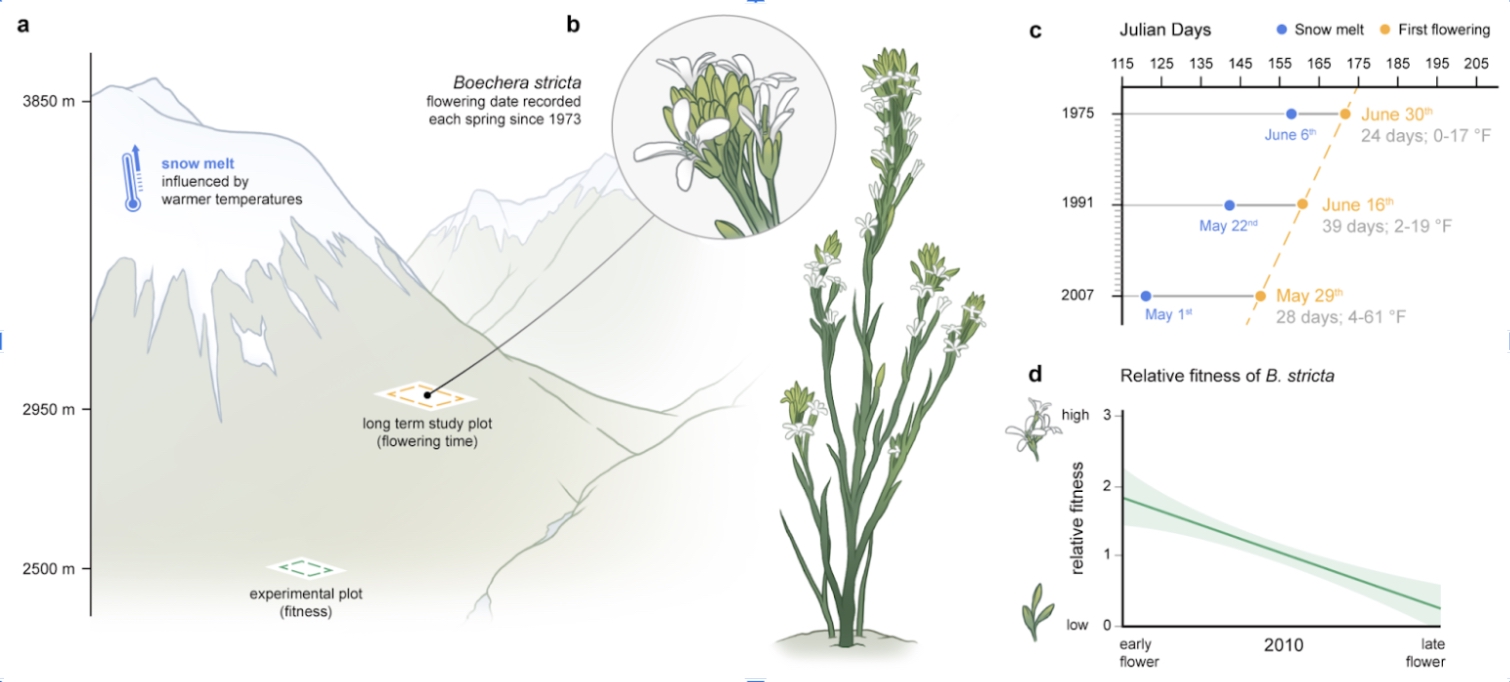

Long-term studies at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Colorado, USA, reveal that Drummond’s rockcress (Boechera stricta), a North American wildflower, now bloom almost 4 days earlier each decade since the 1970s, responding to earlier snowmelt in the region. Long-term field studies are the key to understanding how species in the wild are evolving in response to climate change. (Illustration: Mark Belan/ArtSciStudios)

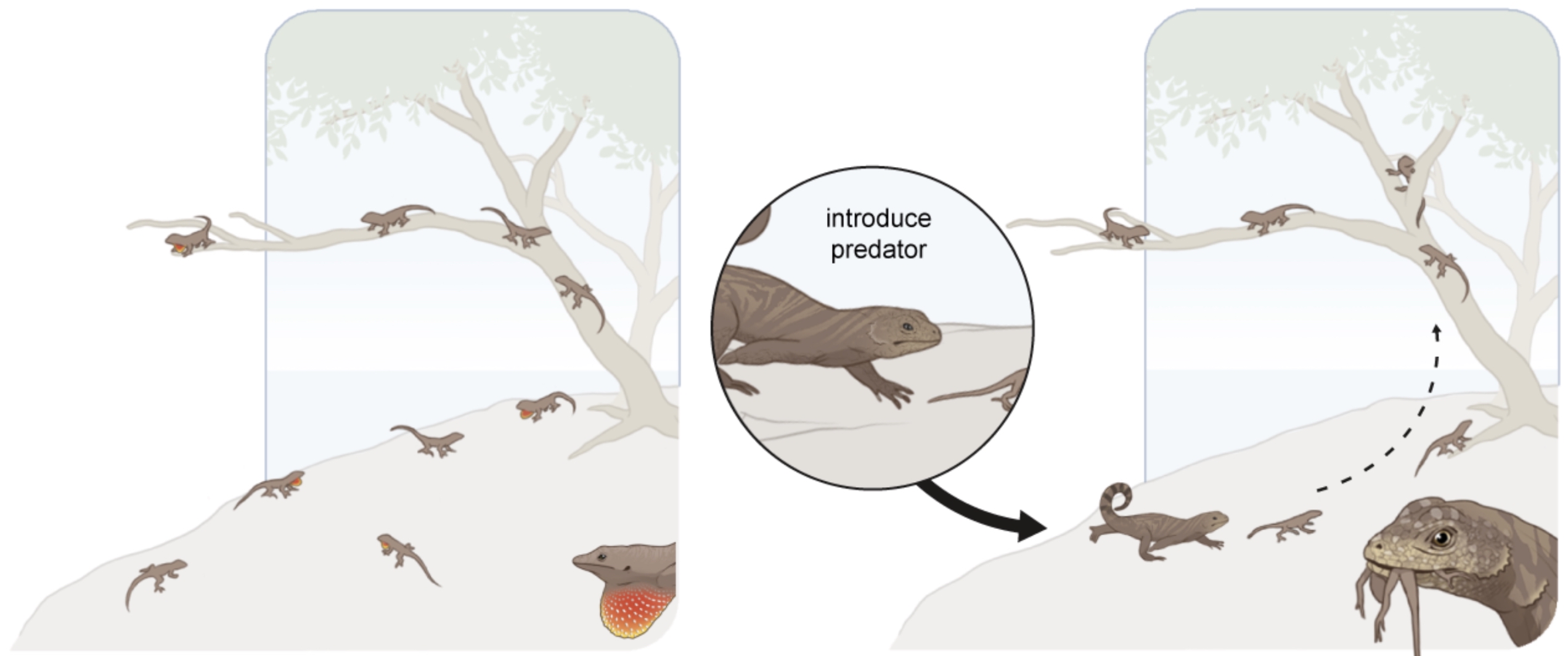

A series of experiment spanning 40 years on small islands in the Bahamas have revealed how prey species, like small brown anole lizards (Anolis sagrei), evolve in response to predators, like the larger curly-tailed lizard (Leiocepahlus carinatus). Importantly, due to the long-term nature of this research, scientists were able to track ecosystem changes in response to this predator-driven rapid evolution. (Illustration: Mark Belan/ArtSciStudios)

Written by Selena Langner

Contact: Jess Hunt-Ralston