Informatics Accelerates Design of Hybrid Membrane Materials for Chemical Separations

Nov 08, 2019 — Atlanta, GA

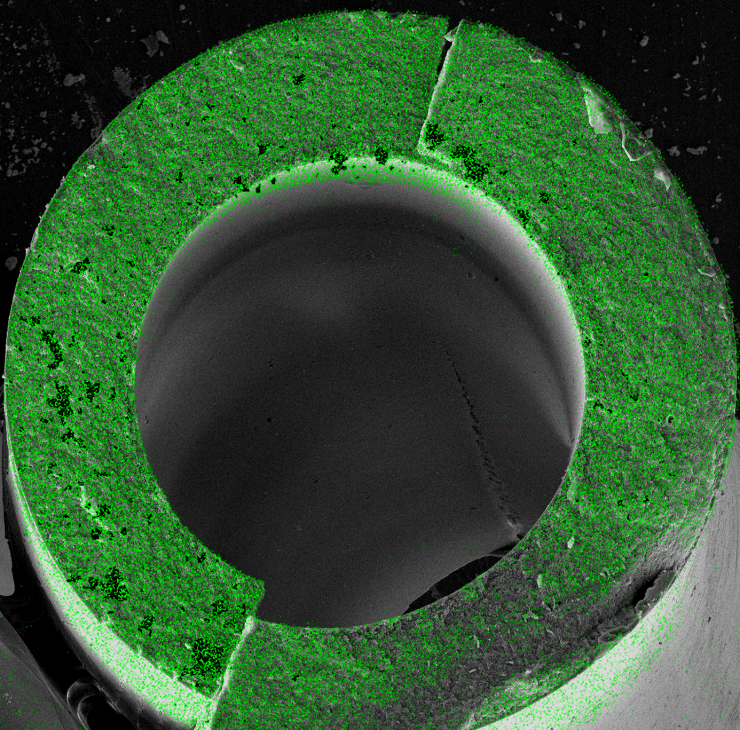

This image shows an elemental map collected with electron microscopy of a fractured cross-section of hybrid hollow fiber membrane with a radius of about 500 μm. Green dots signify locations of the metal oxide within the membrane. This image shows that metal oxide infuses throughout the entire membrane. Microscopy was done by Fengyi Zhang at Georgia Tech’s Materials Characterization Facility.

Vast amounts of energy are consumed each year for chemical separation processes – a precursor to the production of everything from gasoline to food.

A $1.7 million award from the National Science Foundation (NSF) will help a team at the Georgia Institute of Technology develop much cheaper ways to separate chemicals using membranes that could potentially replace energy-intensive distillation processes.

“Membranes have the potential to reduce energy consumption in chemical separation processes by as much as 90%,” said Mark Losego, an assistant professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering, and the principal investigator for the project. “But most of today’s mass-manufactured membrane materials degrade under the chemical conditions required for many important chemical separations.”

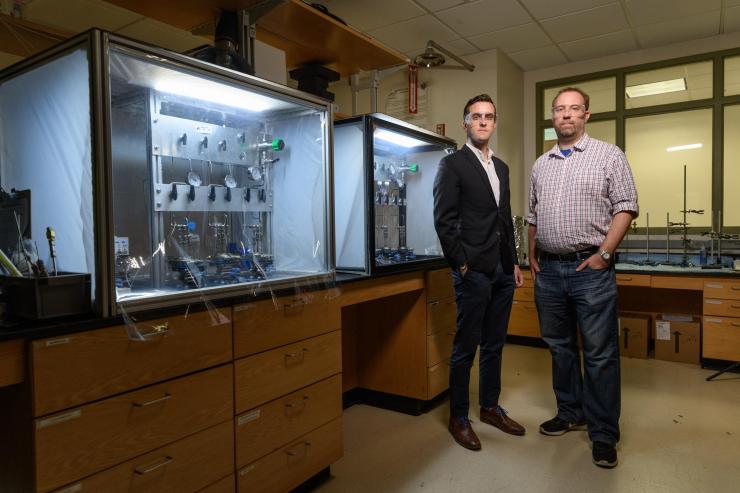

Recently, Losego’s research team in collaboration with Ryan Lively, an associate professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and co-PI on the project, described a new process for taking a polymer-based membrane and infusing it with a metal oxide network. The resulting membrane is far more effective at standing up to harsh chemicals without degrading.

“Plastic membranes are easy to mass manufacture, but they tend to dissolve when used with harsh chemicals, while inorganic membranes are more stable but are difficult to produce in large quantities,” Losego said. “This new process creates a membrane with the best characteristics of both types of materials, one that we call a hybrid membrane.”

The new process involves placing a prefabricated plastic membrane inside a reactor, which exposes the membrane to metal-containing vapors that infuse inside the material. This process is called vapor phase infiltration, and it creates a uniform network of metal oxide throughout the polymer membrane.

The new grant will enable researchers to use computer simulations and data analytics to speed up the process of finding new ways to infuse inorganic materials into polymer-based membranes, with the goal of developing a range of new membranes that could be used for a variety of separation tasks.

“Atomic simulations and data-driven methods such as machine learning can significantly accelerate the design and discovery of new application-specific materials,” said Rampi Ramprasad, a professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering and another co-PI on the project.

The machine learning process involves taking materials data that is already available and using powerful computers to automatically and progressively learn their strengths and weaknesses and how those materials might combine to form materials with new properties.

“These methods allow us to virtually screen thousands of new materials before they are made to provide guidance for the specific types of materials that should be made and tested,” Ramprasad said.

This new NSF program will combine data collected from experiments with computational simulations to accelerate the development of these hybrid membrane materials, enabling new separation processes that lower production costs and are more environmentally friendly.

This new project will be funded through the National Science Foundation’s Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future, Award 1921873. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Ryan Lively, an associate professor in Georgia Tech's School of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering and Mark Losego, an assistant professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering. (Credit: Rob Felt)

Research News