For the Good of Humankind: A Journey in Accessible Design Across Three Continents

How a young girl’s interest in computers led to a research career developing technology for global learners with disabilities — from Turkey to Rwanda by way of Georgia Tech.

Zerrin Ondin-Fraser sits in an assistive technology demonstration space operated by Tools for Life, Georgia’s Assistive Technology Act Program, which is housed within the Center for Inclusive Innovation and Design.

In the Rwandan capital of Kigali, the Masaka Resource Centre for the Blind trains adults in everything from literacy and knitting to farming and massage. The only institution of its kind in the nation, the center operates like a boarding school, housing adult students for six months at a time and providing them with education and rehabilitation services. But the center has a problem.

While instructors can teach their pupils to read and write using a Braille slate and stylus — a simple mechanical tool that creates raised dots on paper — the school only has about 20 such devices, which means students don’t get to take one home when they complete the program. Many graduates subsequently forget what they’ve learned, nullifying all their hard work.

Zerrin Ondin-Fraser, research scientist and interim executive director at Georgia Tech’s Center for Inclusive Design and Innovation, has been working to address accessibility challenges like these for most of her career.

“The easy thing to do would be to send them tons of slates and styluses, but that’s not a real solution,” said Zerrin. “A solution has to be contextually relevant and locally sustainable. That means developing technology that accounts for the culture and the geography and that doesn’t rely on anyone to keep bringing them anything. They need to have the resources to produce the technology by themselves.”

“We don’t get to buy things over here and take them over there. This isn’t a charity; it’s a development project.”

Solutions Within Reach

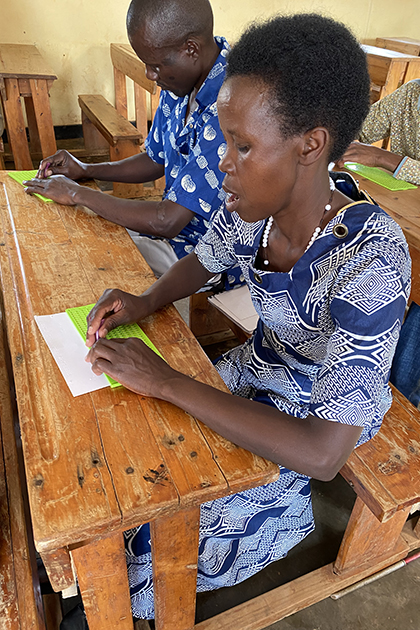

Students at the Masaka Resource Centre for the Blind write in Braille using a slate and stylus.

Zerrin leads the Global Assistive Technology Innovation project, also known as the Confluence, a research initiative dedicated to closing the assistive technology (AT) access gap and addressing accessibility disparities. Under her direction, student and faculty researchers collaborate with local organizations to create sustainable AT solutions for people with disabilities.

Broadly defined, AT refers to any device that, compensating for a loss of function, helps someone accomplish a task that would otherwise be impossible — from reading and writing to moving around and eating. In addition to the slate and stylus, examples of AT include digital Braille notetakers that allow people with blindness or deafblindness to read, write, and use computers; beacon mapping systems that interact with smartphones to help blind users navigate spaces; and specially designed food utensils that enable people with tremors to feed themselves.

To accelerate the Confluence’s impact, Zerrin created a corresponding Vertically Integrated Project (VIP), now in its third semester, that allows students to advance the hub’s research for course credit. For more than a year, the group has worked with with local nongovernmental organizations, universities, hospitals, and schools to identify some of Kigali’s most pressing accessibility needs. She leads the VIP alongside Ellen Bassett, dean of the College of Design, and Anthony Giarrusso, associate director of the Center for Spatial Planning Analytics and Visualization. Together, they’ve taken the class to Rwanda twice since the project launched in Spring 2024.

The Masaka Resource Centre for the Blind is one of the Confluence’s first partners. Under Zerrin’s leadership, students from the VIP have teamed up with the school to design a slate and stylus that can be made using locally accessible materials and manufacturing methods.

In February 2025, students from Zerrin’s Global Assistive Technology Innovation VIP traveled to the CECHE Foundation in Kayumba, Rwanda, to demonstrate the wheelchair chassis they designed for the school. Here, a CECHE Foundation student and his mother celebrate the new design with Hannah Koppel (second from left), Andrea Fairchild (second from right), and Ben Soboloff (right).

“We don’t get to buy things over here and take them over there,” Zerrin explained. “This isn’t a charity; it’s a development project.”

In the village of Kayumba just outside Kigali, another team from Zerrin’s VIP works with a disability-inclusive school operated by the CECHE Foundation that cares for young children with cerebral palsy. Children with this disability often struggle with sitting up. To help hold their students safely in place, the school’s staff designed and used a postural support chair made from cardboard boxes. However, the chairs were not mobile, creating problems for both the children and their caretakers.

The wheelchairs commonly used in the U.S. are not a viable option, said Hannah Koppel, a biomedical engineering student taking Zerrin’s VIP course for the third straight semester.

“Traditional Western wheelchairs are not locally produced, and the added costs of importation and market fragmentation make them far too expensive for most of the people who need them,” she said. “They run about $130 per wheelchair, not counting import fees, for people who make, on average, the equivalent of about 70 cents a day.”

Traditional wheelchairs also aren’t designed for Rwanda’s unpaved roads, rough terrain, and alternating climate of arid and rainy seasons, which means they’re not likely to last long.

“Even if someone were to obtain one,” said Hannah, “it would be almost impossible to fix if something broke due to a lack of materials, tools, or familiarity with the correct repair process.”

The parents of these children needed something that could be easily transported on a motorbike and would be durable enough to withstand the high heat, heavy rain, and road debris that come with extended outdoor use. In response, Zerrin’s team spent months working with the school’s staff to design a chassis that not only met the families' unique needs but also could be easily produced and installed on-site using readily available materials.

They demonstrated their design during the VIP’s second trip to Rwanda in February, working alongside CECHE Foundation staff to construct four made-to-measure chassis that turned the cardboard chairs into wheelchairs. The collaborative partnership will continue, but the school already has what it needs to design and produce new iterations without outside assistance.

This is just the beginning for the Confluence, a project Zerrin hopes will last 20 years or more. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 3% of people with disabilities have access to AT, and much of the AT they have is likely inadequate.

For Zerrin, that means there’s a lot of work to be done, but the Confluence is already making an enormous difference — not just abroad but also on Georgia Tech’s campus.

“It’s about being valuable to the community, to the country, and to humankind; it’s about making sure your existence means something to the rest of the world. That’s how my parents lived, and they built these ideas into my childhood.”

Captivated by Computers

Zerrin celebrates at commencement after earning a Ph.D. in instructional design and technology from Virginia Tech in 2015.

A native of Istanbul, Zerrin says she enjoyed a vibrant, cheerful childhood filled with constant play and adventure. She explored a range of evolving interests in her early years, but none of them took root until the first personal computers arrived at her middle school in the early 1990s.

For Zerrin, the personal computer opened an entirely new world that immediately captivated her. She quickly taught herself MS-DOS and dabbled in basic coding languages, eventually persuading her parents to buy their own IBM. As the number and variety of computers grew at her middle and high schools, so did the time she spent in their labs.

Out of all the things computers could do, Zerrin felt the greatest attachment to their capacity to enhance learning; by the time she finished high school, she knew exactly what she wanted to study. Enrolling at Istanbul’s Marmara University, she earned a degree in computer science education and instructional technologies, an interdisciplinary field that blends coding and design with cognitive science and pedagogy.

From the beginning of her studies, she felt irresistibly drawn to use technology to advance accessibility even though her program did not specialize in this field.

“I decided I would use everything I know for people with disabilities — that I was going to build something for this demographic,” she said. “It’s about being valuable to the community, to the country, and to humankind; it’s about making sure your existence means something to the rest of the world. That’s how my parents lived, and they built these ideas into my childhood.”

After graduating in 2002, she moved on to a master’s program at nearby Boğaziçi University and supported herself with jobs as a faculty instructor and instructional designer. When she wasn’t working or studying, she spent much of her time volunteering at her university’s disability support center, where she created audio recordings of books for blind students. She earned her master’s in 2007 and continued to teach for a few years until — driven to take her studies and career further — she found a Ph.D. program at Virginia Tech that seemed like a perfect match.

By 2015, she had earned a Ph.D. in instructional design and technology and a graduate certificate in human-computer interaction while working as both a teaching and a research assistant.

A main reason for going to Virginia Tech was to work in the school’s AT research lab. Zerrin frequented the center almost every day — striking up conversations, explaining her research interests, discussing accessibility, using and testing their AT — until they hired her. She worked there for several years, blending federally funded research with daily interactions with students and assistive technologies. When she wasn’t researching, she was transcribing notes into Braille, creating digital versions of course materials, or installing Braille labels in the food hall so blind students could find the utensils they needed without hurting themselves. She thrived on this combination.

“One out of every six people has a disability. That means it’s very normal to have a disability. And yet, people with disabilities have always been marginalized, their needs have always been neglected, and they must continually fight for their rights any way they can.”

Perfect Fit

Zerrin demonstrates a weighted stuffed animal made by Cuddle Works, which can latch behind a person’s neck to mimic a hug. Designed to promote relaxation, reduce anxiety, and provide a feeling of security, the plush toy can help calm and relieve stress for children with autism, sensory processing disabilities, and more.

After completing her dissertation on designing online learning platforms for blind students, Zerrin was finally ready to find the job she’d been preparing for since high school. With her background and experience, she had numerous opportunities to choose from — from academia to instructional design to user experience.

“Academia had always been attractive to me, but I didn’t want my research to just go into papers that might not affect anyone’s life,” she said. “From the beginning, too, I think I always knew my career would be related to technology, but my work had to connect to something bigger — something greater than technology itself, something attached to everyday human life.”

Before long, she came across a job listing at Georgia Tech that checked all her boxes and more, bridging applied research and development with community outreach and education. She started work at the Center for Inclusive Design and Innovation (CIDI) as a research scientist in late 2015.

Housed within the College of Design, CIDI merges research and service under one roof. On one side of the center, teams of research scientists develop evidence-based technologies and solutions for people with disabilities, such as new designs and devices. On the other side, accessibility experts provide students throughout the University System of Georgia with accessibility services, including captioning, Braille transcriptions, and digital book conversions. CIDI also houses Tools for Life, the state’s Assistive Technology Act Program, which helps connect Georgia’s disabled community with devices that can help them lead independent lives.

Zerrin (center) meets with the University System of Georgia Regents’ Advisory Committees on Accessibility and Disability Services at CIDI.

“CIDI is almost a unicorn,” said Zerrin. “Here, I get to research, innovate, and design solutions that could impact someone’s life, and I get to work with a strong service division at the same time — meaning I get to do what I’ve always wanted to do.”

In September 2024, Dean Bassett appointed Zerrin to lead CIDI as interim executive director. Since taking the helm, Zerrin has worked to steer the center to a position of greater involvement within Georgia Tech while taking measures to strengthen its culture and organization. In particular, she is trying to better integrate the center’s work with researchers in the College of Design and across the Institute to drive collaboration and increase their joint impact.

“Zerrin’s real strength is empathy,” said Dean Bassett. “She listens closely. In her time as interim director, she has provided calm leadership and inspiration to all the faculty and staff at CIDI. She has also facilitated long-overdue discussions about the center’s mission and direction and ways in which staff and faculty can flourish in their careers. Her leadership has made the center stronger and better poised to continue its excellent work.”

The Real Dream

As interim executive director, Zerrin has sought to increase CIDI’s involvement and integration across Georgia Tech.

From her humble beginnings learning the command line on her school’s rudimentary PCs, Zerrin has been following a path that has taken her across the globe in pursuit of a fundamental question: how technology can — and how it should — change our experience of the world.

“The way I see it, technology is simply something that makes things possible,” she said. “And it has the power to improve your life if you know how to design it.”

Problems arise when designers fail to account for groups that make up as much as 16% of the global population.

“One out of every six people has a disability,” Zerrin said. “That means it’s very normal to have a disability. And yet, people with disabilities have always been marginalized, their needs have always been neglected, and they must continually fight for their rights any way they can.”

From architecture and urban planning to home appliances and software development, inaccessible design creates formidable challenges that can affect every aspect of life for the disabled community. Zerrin’s mission is to change the design paradigm that treats disabilities as negligible exceptions to the norm — and, with any luck, make her own job obsolete one day.

“If we have an inclusive, accessible world — one that finally acknowledges that disabilities are normal and designs everything accordingly — I don’t have to have my job anymore,” she said. “That’s the real dream. This would mean, when you go to your workplace, you don’t have to ask for accommodations because they’re already built in. If you are blind, you don’t have to hunt for accessible books because all the books are already accessible. It means inclusivity is a fundamental part of the design from the beginning rather than something added on afterward.”

It’s a brave, bold vision. And while progress can be slow, Zerrin can take heart that her life’s work is moving the world closer to that dream.

“I don’t know if it gets much better — your research, your teaching, and everything you do creating some sort of positive change in someone’s life. And that’s why I am so in love with what I do.”

Writer and Media Contact: Benjamin Hodges, Senior Writer/Editor, Executive Communications | bhodges35@gatech.edu

Photos: Christopher McKenney, Video Producer, Research Creative Services and courtesy of Zerrin Ondin-Fraser

Video: Christopher McKenney, Video Producer, Research Creative Services

Series Design: Daniel Mableton, Senior Graphic Designer, Research Creative Services

Learn More

The Center for Inclusive Design and Innovation (CIDI) is part of Georgia Tech’s College of Design. With its rich history of providing accessible solutions to an underserved community, CIDI has positioned itself as a leader in accessibility and inclusion. CIDI is committed to promoting technological innovation; developing user-centered research, products, and services for individuals with disabilities; and addressing needs in higher education, government, non-profits, and corporations by providing accessibility services for our clients.