Since the publication of this feature, Trajkova has transitioned to the role of Assistant Professor of Computer Science at Kennesaw State University and is no longer with Georgia Tech.

On Pointe: How a Former Ballerina Brings Artificial Intelligence to Dance

Milka Trajkova discovered human-computer interaction by accident. Now she’s using it to create technology to improve fellow ballerinas’ skills.

Trajkova hopes to prevent injury with her research, but she also wants help ballet teachers teach classes more efficiently.

Milka Trajkova grew up wanting to be a professional ballet dancer — and she was, until an injury closed the curtain on her career. But this didn’t end her interest in ballet.

While Trajkova doesn’t dance anymore, she builds artificial intelligence (AI) apps to help dancers perfect their technique and improve their performance. Trajkova is a visiting lecturer and research scientist in Georgia Tech's Expressive Machinery Lab at the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts (IAC). She uses AI to turn artistic movement into data and increase respect and understanding for the technical skills required in dance. Her work could soon be seen on stage.

“Human-computer interaction is a fusion of design, psychology, and technology, and it opened my eyes. HCI is about understanding people first, then shaping technology around them — so technology doesn’t just work, it works for us.”

Act I: Ballet Beginnings

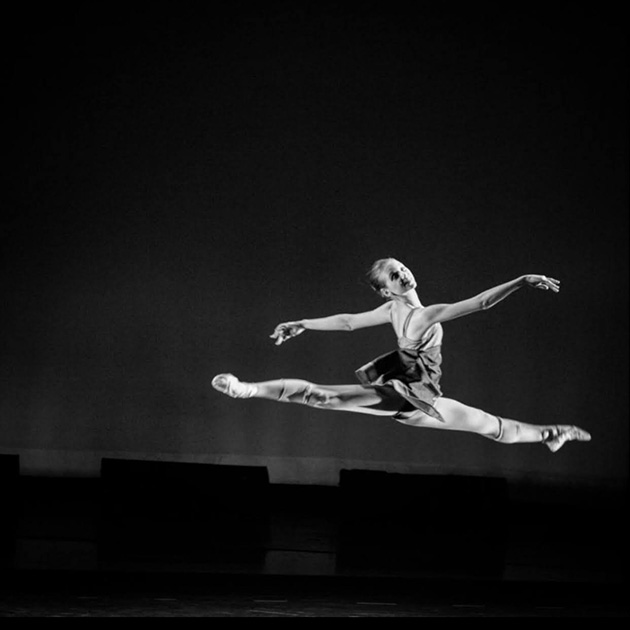

Trajkova, age 14, performing “Figures” at Maryland’s CityDance School and Conservatory.

Trajkova first laced up her ballet shoes at age 5, when her family still lived in Macedonia. Her instructors quickly realized she had an aptitude for dance, but her family immigrated to America the following year, and she lost interest. One year later, Trajkova wanted to get back on the dance floor. The costumes, the classical music, the storytelling — all of it thrilled her. And while she chasséd through the D.C. suburbs growing up, Trajkova regularly went back to Macedonia and kept in touch with the ballet company there.

When she was 17, Trajkova was given the opportunity to join her childhood company, the Macedonian Opera and Ballet, as part of the corps de ballet. She moved back to Macedonia to dance. Despite achieving her childhood dream, Trajkova knew she needed a backup plan. So, she enrolled in the only accredited English-language program at the capital’s Southeast European University (being more fluent in English than her native tongue). The program was in information systems management (ISM), offered in collaboration with the London School of Economics. In the mornings, she took classes, then rushed to the theater for warm-up class and afternoon rehearsals, and finished her studies in the evening.

ISM wasn’t a major she ever expected to choose.

“Both of my parents are engineers, and I always said growing up, ‘Whatever you do with computers, I never want to do that,’” Trajkova remembered. “But that was the only program available, so I just dove into it.”

In one class, she learned about human-computer interaction (HCI). Trajkova was immediately intrigued.

“HCI is a fusion of design, psychology, and technology, and it opened my eyes,” she says. “HCI is about understanding people first, then shaping technology around them — so technology doesn’t just work, it works for us.”

In her final year, she needed a thesis topic. One day, she pulled up Google Scholar and typed “ballet technology.”

“It was like opening a door to another world,” she said. “That's when things really took off, and I found what I wanted to study.”

There, Trajkova found a paper about a computer program that could assess whether dancers were performing ballet movements correctly. She reached out to the original researcher and asked if she could user-test the program, having access to research subjects at the ballet school where she practiced daily.

The rest was history.

Act II: From Dance to Data

Trajkova, age 17, in her first performance of Swan Lake for the Macedonian Opera and Ballet.

As Trajkova was discovering HCI and working on her research, she also developed a debilitating toe injury. Doctors warned her she would have to endure constant pain if she wanted to keep performing. At the age of 20, after only three years at the company, Trajkova retired from ballet. The decision was devastating.

“It was very hard to deal with for a long time,” she said. “But my research gave me a purpose again, and I wanted to give back to an art form that gave me everything.”

Her undergraduate thesis on the plié was her opening act. Trajkova then pursued both a master’s degree in HCI and a Ph.D. in informatics at Indiana University. She wanted to quantify ballet movements as data to train an AI model. From there, she believed the AI program could be used to enhance dancers’ technique and performance.

The practice of applying data to performance is common in other sports. Think of the book and film Moneyball, which describes how team managers applied statistics to build the best baseball teams.

“When you walk into a ballet class, the highest form of technology dancers use daily is a mirror,” Trajkova said. “I wanted to change that.”

But the task she set for herself wasn’t easy.

Trajkova, age 17, in a photo shoot at the CityDance Conservatory in Maryland.

Ballet is often perceived as more of an art form than an athletic pursuit worth quantifying. Yet behind every seemingly fluid movement is correct technique. Breaking down technique from a motor-learning perspective can pinpoint where dancers go wrong. Using this data, Trajkova created aiDance, a dashboard that helps dancers build visual awareness of their technique and gain actionable insights to improve performance.

The idea of using AI at the ballet barre initially made her fellow dancers skeptical, but Trajkova’s background helped. She wasn’t a researcher who merely had seen one production of the Nutcracker; she had been in those same satin pointe shoes.

“People like to create a kind of mystery around the ballet world, when, at the end of the day, dancers are athletes who need to be well-equipped to perform any role,” Trajkova said. “They need to know how they can refine their technique and maintain their body for the growing demands of the art form.”

Preventing injury is the emphasis of Trajkova’s research, but she also wants to aid ballet teachers as much as students. In a typical ballet class, dozens of dancers share the attention of just one teacher, making personalized and individualized feedback nearly impossible. Trajkova sees her work as a way to supplement — not replace — teachers, helping them gain a deeper understanding of each student’s progress and needs.

She conducted most of her Ph.D. research during the Covid-19 pandemic, when her ballet conservatory in Maryland recorded all classes on Zoom and Microsoft Teams. From those videos, she was able to extract meaningful features of ballet motion and train a machine learning model to identify a specific error in a plié.

“When you walk into a ballet class, the highest form of technology dancers use daily is a mirror. I wanted to change that.”

Act III: Choreographing a Future

Trajkova created aiDance, a dashboard that helps dancers build visual awareness of their technique and gain actionable insights to improve performance.

During her Ph.D. program, Trajkova met IAC Professor Brian Magerko at an academic conference. Magerko was also doing dance and AI work, and Trajkova knew he had to be on her dissertation committee. Similarly, Magerko thought Trajkova would be a great fit at Georgia Tech. In 2021, she interviewed for her current research scientist role and arrived on campus shortly after.

At Tech, Trajkova changed her dance research from ballet to improvisational movement. Magerko’s lab was designing an improvisational dance partner called LuminAI, which uses AI to transform human movement into new movement. This fosters a co-creative exchange between human and machine. The project, funded by the National Science Foundation, was the first to culminate in both a long-term improvisational dance class study and a public performance of AI-driven improvisation.

Trajkova’s own research has further widened in scope; now she wants to decode a broad spectrum of artistic movement. From rhythmic gymnastics to ballet, adding data to “artistry” has been nearly impossible until AI. Last year, Trajkova hosted a workshop with 12 experts from different disciplines from around the world — including human-computer interaction, data visualization, bioinformatics, music and robotics, ballet, biomechanics, sports science, and gymnastics — to discuss how they could start this analysis.

Dance as an art form isn’t center stage in this work. There are many other applications, including healthcare. Dance therapy can be used to help with Parkinson’s disease rehabilitation, for example.

“Most physical rehabilitation has been focused on function, like picking up a cup,” Trajkova said. “We’re asking how we can reframe rehabilitation to make it feel more artistic and enjoyable for people — because the more engaging it is, the more it can support neuroplasticity and lasting recovery.”

This work has made Trajkova’s post-performance life more enjoyable, too. She may have put away her pointe shoes, but she remains engaged with the ballet world.

“My life has come full circle because I started with ballet, and now I can contribute to dance in my own way,” she said. “It’s rewarding that I still get to be part of the dance community and interact with dancers.”

Writer and Media Contact: Tess Malone, Senior Research Writer/Editor, Research Communications | tess.malone@gatech.edu

Video: Christopher McKenney, Video Producer, Research Creative Services

Photos: Christopher McKenney and courtesy of Milka Trajkova

Copy Editor: Stacy Braukman, Senior Writer/Editor, Institute Communications

Series Design: Daniel Mableton, Senior Graphic Designer, Research Creative Services

About the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts

Georgia Tech’s Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts offers innovative, human-centered perspectives at the intersection of the humanities, social sciences, arts and STEM.

Its six schools — Economics; History and Sociology; Literature, Media, and Communication; Modern Languages; Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School of Public Policy; and the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs — along with 18 research centers, provide programs and experiences that redefine the role of the humanities and social sciences. Nearly 350 tenured, tenure-track, non-tenure-track and permanent research faculty work in the college.

Learn More

To explore careers in research, visit the Georgia Tech Careers website. To learn more about life as a research scientist at Georgia Tech, visit our guide to Research Resources or explore the Prospective Faculty hub on the Office of the Vice Provost for Faculty website.