New Multidisciplinary Initiative Marks Golden Age for Space Research

The Georgia Institute of Technology has a long history in space research and exploration, from educating astronauts to developing and controlling spacecraft that can travel across the solar system.

Some Georgia Tech researchers solve cosmic mysteries such as how supermassive black holes were born — and others now are getting a better, sharper look at those black holes. There are investigators searching for the origins of life, and some leading multi-institutional projects exploring questions of how life evolved and about the presence of water in the lunar environment to enable the return of human explorers for a sustained period.

And that barely gets us into orbit — there’s a lot of Georgia Tech in space. Much of the work is supported by longtime Georgia Tech partners like NASA, the National Science Foundation, and the Department of Defense. But as space becomes more accessible, affordable, and necessary for commercial activity — and therefore more crowded — Tech is also developing expertise in space policy and business.

And now, plans are underway for the next big phase of Georgia Tech’s outer space mission with the launch of the Space Research Initiative (SRI) on campus. The SRI team will work to strengthen interdisciplinary relationships in space research at Georgia Tech, which will lead to creation of an Interdisciplinary Research Institute (IRI) by 2025.

“This is a golden age for space exploration in general, and in particular at Georgia Tech, especially when we think about what is happening in our lifetime, and what will happen in the lives of the students coming through this university,” says Glenn Lightsey, interim SRI director.

“One of the strengths of this planning effort was how the committee managed to include so many sectors of campus. We’re very enthusiastic about space research at Georgia Tech and how it will fit into our interdisciplinary research focus areas.” —Julia Kubanek

The initiative is being developed by a steering committee of faculty members across campus and chaired by Lightsey, who made a year-long study of Georgia Tech’s space research universe. They gathered input from students and about 100 faculty representing all of Georgia Tech’s colleges, the Office of Commercialization, the Library, Enterprise Innovation Institute (EI2), and Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI).

And they made the following recommendation to the executive vice president for Research’s office: Create an IRI focused on interdisciplinary space research, incorporating existing centers and integrating the work of existing labs and programs. The Space Research Initiative is the first step in this process. Between now and summer 2025, the team will work to strengthen the interdisciplinary space research community at Georgia Tech and set the foundation for the future IRI.

“One of the strengths of this planning effort was how the committee managed to include so many sectors of campus,” says Julia Kubanek, vice president for Interdisciplinary Research. “We’re very enthusiastic about space research at Georgia Tech and how it will fit into our interdisciplinary research focus areas.”

Space Is the Place

The timing for the initiative could not better.

“The university and the faculty here have put a high priority on doing research, and expanding our focus in space,” says Lightsey, former director of both the Space Systems Design Lab (SSDL) and the Center for Space Technology and Research (CSTAR).

“It’s happening across the board, spanning all the different ways we can engage in making progress in space,” he adds. “That includes technology and science, obviously, but also security, policy, business, even culture and art — so much of which is focused on space and space exploration. The science fiction of 50 years ago is the science and engineering of today.”

Right now, there are more than 8,300 satellites circling the planet. Every three days, on average, a rocket launches from Earth, about half of them from Cape Canaveral on Florida’s Atlantic coast, carrying spacecraft and other payloads, delivering the foundation of a new space age.

“The space industry — the science and technology component, all the commercial enterprises, including tourism — is projected to be more than a trillion dollars by 2030,” says Thom Orlando, Regents’ Professor in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry who leads the $7.5 million Center for Lunar Environment and Volatile Exploration Research (CLEVER).

“Space medicine and human exploration might even be one of the industries that emerge in Atlanta. I view the space research IRI as a pathway to these opportunities.” —Thom Orlando

A co-founder and former director of CSTAR, Orlando has long supported the concept of a space research IRI and expects it will help drive regional economic development, potentially creating new business opportunities and jobs for talented graduates who currently leave the state to join NASA or SpaceX or some other enterprise. He also sees an IRI as a potential facilitator for a developing area of research: space health and medicine.

“We have to consider the human component when we think about space exploration,” says Orlando, whose lab has been involved in NASA’s Artemis program, working on technology that will keep astronauts safe in their suits when they return to the moon. Artemis II (with a targeted launch of September 2025) will send a crew of four to orbit the moon, a first test for NASA’s human deep space exploration capabilities.

“Our next generation of explorers will be working under extreme conditions and living in an autonomously controlled environment for an extended length of time, on the moon,” he adds. “As we consider the growth of our space research enterprise, I think we’ll have opportunities to integrate experts at the Emory School of Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, and the University of Georgia in a statewide alliance focused on human space exploration. Space medicine and human exploration might even be one of the industries that emerges in Atlanta. I view the space research IRI as a pathway to these opportunities.”

Part of the Solution

As an aerospace engineer, Lightsey has never really considered the challenges of getting into space as technical limitations. They’ve been economic.

“Twenty years ago, space was only accessible to governments. It was too expensive for everyone else. But that’s all changed,” he says. “The lower cost of launch vehicles, the more rapid cadence of launches, the miniaturization of systems — all of these things have helped transform the space industry. The more stakeholders you have, the more affordable it gets.”

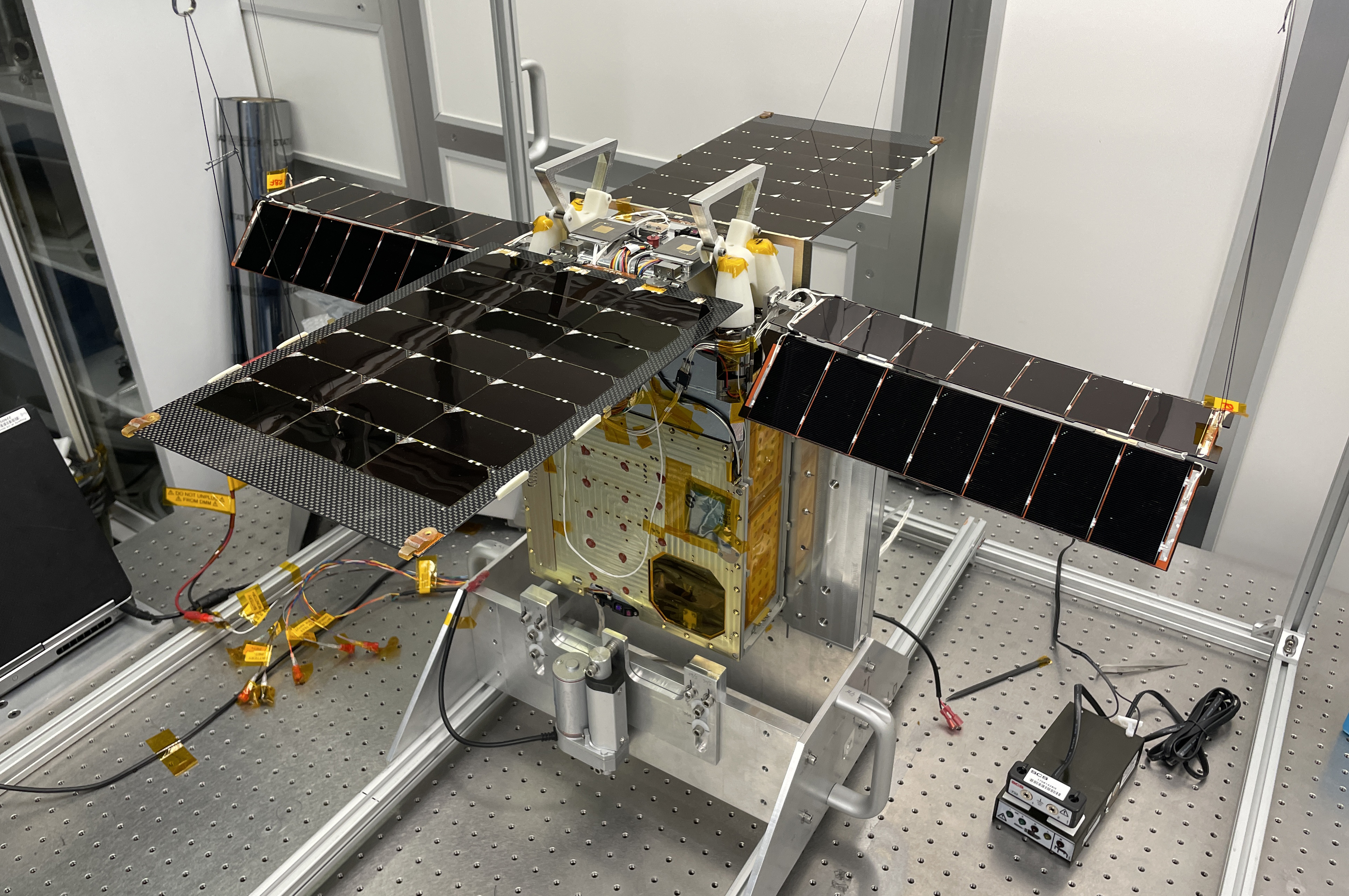

Five or 10 years ago, Georgia Tech didn’t have satellites in space. Now there are almost a dozen.

“The fact that a university can do this is amazing,” Lightsey says. “The cost has come down that much, which means universities can participate, which provides incredible experiences for our students at the beginning of their careers.”

“The work we do in space is important for the world we want to live in 100 years from now. Space is a big part of our increasing understanding of climate change, and to improving the environment, providing fresh water to people all over the world, improving crop yields, and basically managing the Earth for the betterment of everyone. Space is going to be an essential part of any solution.” —Glenn Lightsey

His students are designing satellites, then operating them as they conduct missions in space.

Aerospace engineering undergraduate Dalton Luedke has designed a new rocket engine for NASA, a potential big step in deep space exploration. Other students, like Ph.D. candidate Emmy Hughes, are more grounded in their focus. A planetary geologist in the lab of James Wray, she published a recent study of salts and the history of water on Mars.

“The breadth of opportunities for students working in space research is staggering,” Lightsey says. “It’s inspiring, and I see it as one of the primary missions of a research institute, bringing this community of student and faculty researchers together.”

Beyond that, he says, are more pragmatic aims of the IRI, a global purpose, the 20,000-mile view that only an outer space vantage point could provide in the years to come.

“The work we do in space is important for the world we want to live in 100 years from now,” Lightsey says. “Space is a big part of our increasing understanding of climate change, and to improving the environment, providing fresh water to people all over the world, improving crop yields, and basically managing the Earth for the betterment of everyone. Space is going to be an essential part of any solution.”

Related Links

News and Feature Stories

- What Can Space Teach Us About Sustainability?

- NASA Selects GT Researcher to Study New Breathing Tech

- Proof of a Persistent Black Hole Shadow

- Georgia Tech Researcher Leading $6 Million NASA Astrobiology Study

- NASA Lunar Research and Exploration Center Lands at Georgia Tech

- Students Control Interplanetary Spacecraft

- A Piece of the Moon at Georgia Tech

- From Army Medic to NASA ‘Space Plumber’

- Space Wargaming: GT Researchers Leading New Series

- From Seafloor to Space: Shining Light on Climate and Astrobiology

- Students Develop Better Packing System for Rockets

Research Groups

- Center for Space Technology and Research (CSTAR)

- Space Systems Design Laboratory (SSDL)

- Georgia Tech Astrobiology Program

- Center for the Origin of Life

- Space Exploration Analysis Laboratory (SEAL)

- Planetary and Space Physics

- Center for Relativistic Astrophysics (CRA)

- REVEALS

- Joint Advanced Propulsion Institute (JANUS)

- PLANETAS

- Creative Destruction Lab

- Dynamics and Control Systems Laboratory

- Predictive Analytics and Intelligent Systems (PAIS)

- Space Systems Optimization Group

- Low Gravity Science and Technology Lab