Robot Guitarist Plays With Human Expressivity

Legendary blues guitarist B.B. King famously said, “I wanted to connect my guitar to human emotions.” In a way, that’s exactly what researchers in the lab of Gil Weinberg are trying to do in developing their Expressive Robotic Guitarist (ERG).

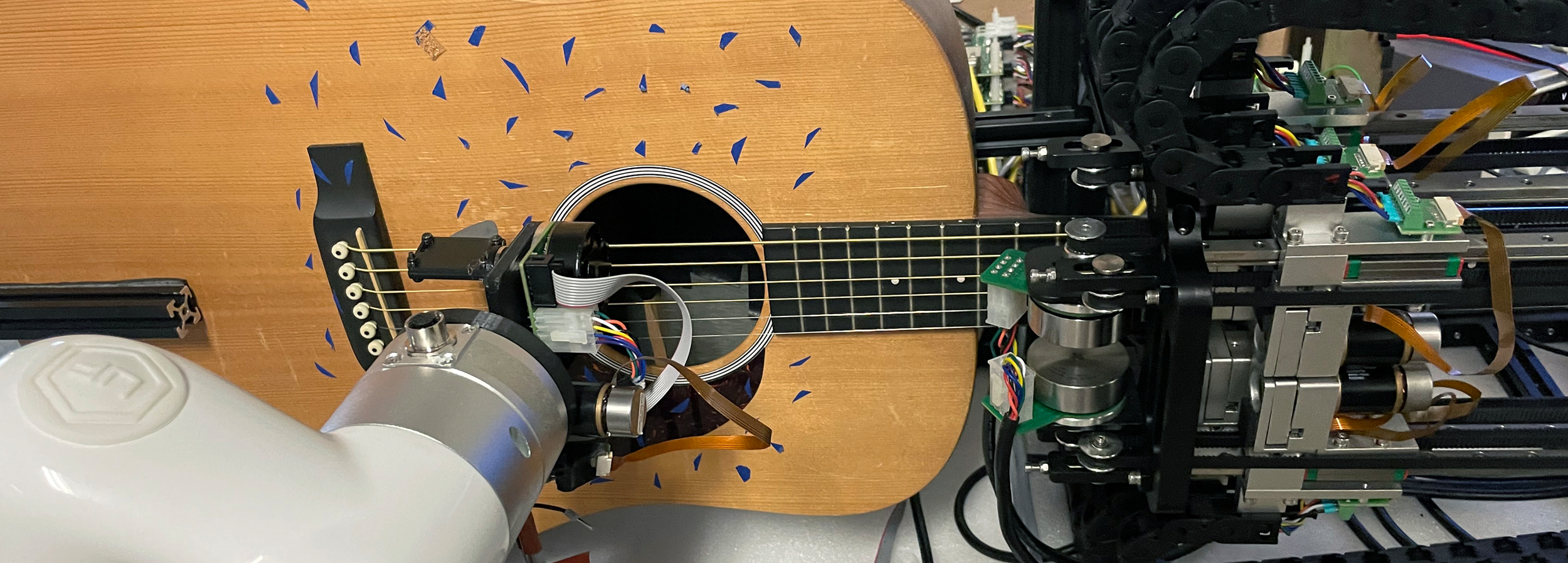

Headless, with mechanical “hands” plucking strings and gliding silently across the Martin acoustic guitar bridge, it may have an imbued sense of good taste in instruments, but it probably won’t be mistaken for a musician with a pulse. At least, not in the conventional sense.

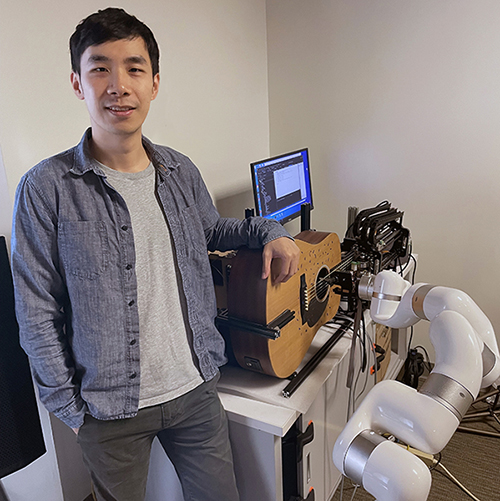

“Our aim was to build a musician first and foremost, and it just happens to be a robot,” said Ning Yang, project leader and first author the paper, “Design of an Expressive Robotic Guitarist,” which is being published in November’s edition of the journal IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters. “In designing our robot musicians, we think how human musicians would express themselves.”

That is part of the essential theme in the Weinberg lab, where researchers already have developed a musician called Shimon, the singing, songwriting, marimba-playing robot. They’ve also created a robotic prosthesis for a drummer, a wearable robotic third limb that transforms musicians into three-armed drummers, and other music-assisting robots.

“We always put the focus on musicianship first,” said Weinberg, founding director of the Georgia Tech Center for Music Technology, where he leads the Robotic Musicianship group. “They are musicians, capable of creating expressive, creative, and emotional performances. But they are also robots.”

The Weinberg group and other researchers have made significant progress in robotic musicianship in recent years, particularly in areas such as machine learning and improvisation, and in generative interactions. These advances have made robot-human interactions more engaging and interesting to watch.

But less progress has been made in developing acoustic expressivity in robotic musicians. For a robot to perform expressively, the research team reasoned, it needs to play with a versatile set of techniques and styles on its instrument. That made the guitar a perfect addition to the mechanized ensemble growing in Weinberg’s lab.

“The acoustic guitar is a complicated instrument to play. It requires more dexterity and finger control to produce basic musical responses than a marimba, for example,” said Weinberg. “The guitar is one of the most expressive musical instruments, responding to subtleties in timbre, dynamics, and timing, through a wide range of styles and techniques.”

“We always put the focus on musicianship first. They are musicians, capable of creating expressive, creative, and emotional performances. But they are also robots.” —Gil Weinberg

The Mechatronics Approach

Weinberg — whose research team always includes musicians who also happen to be computer scientists, electrical engineers, mechanical engineers, or physicists, among other things — explained that his approach to robot musicianship has two main elements: what the robot plays and how it plays.

What it plays depends on what it hears. Then, through machine learning, the robot’s complex, algorithmic brain can process that information and determine how to respond or interact musically, teaching itself how to improvise with human accompanists. Some of the earlier creations from Weinberg’s lab, like Shimon, are built with this in mind. But the Expressive Robotic Guitarist isn’t ready for that kind of interaction yet.

This project was focused on the how. “That’s the mechatronics approach, which focuses on how the sound is produced, rather than on what notes should be played,” Weinberg said. “This time, we focused on the acoustic generation part of the equation and went from there.”

Mechatronics is the integration of mechanized systems with electronic and computer systems, and Weinberg’s lab is well-suited to this kind of work. The ERG project is the product of Yang’s Ph.D. dissertation, “Mechatronics driven design approach for musical expressivity in robotic musicianship.” Part of his work included enhancements to earlier inventions. For instance, Shimon got a new striking system, giving it a wider dynamic range, faster speed, and more techniques that gave it humanlike expressivity on the marimba.

For the ERG, Yang and his collaborators — many of them also musicians — analyzed and modeled how humans play an acoustic guitar, creating a robot with a right-arm module for strumming and picking and a left-hand apparatus for pressing the strings. Yang, who is a keyboardist, recruited guitarists, including his college roommate and bandmate, to serve as models for the ERG.

Using audio recordings of the guitarists playing various pieces of music and video of their hand gestures, the researchers analyzed how humans strum, pick, shift frets, perform techniques like hammer-ons and slides, and otherwise affect the dynamic range of performance. The guitarists were encouraged to use their tools of musical expression: alternating tempos (the speed at which they played), dynamics (how loudly or softly they played), articulation (staccato notes versus drawn-out, bended notes, etc.).

“We didn’t want them to play like robots,” Yang said. “We wanted them to play like themselves.”

“That’s the mechatronics approach, which focuses on how the sound is produced, rather than on what notes should be played. This time, we focused on the acoustic generation part of the equation and went from there.” —Gil Weinberg

Playing With Feeling

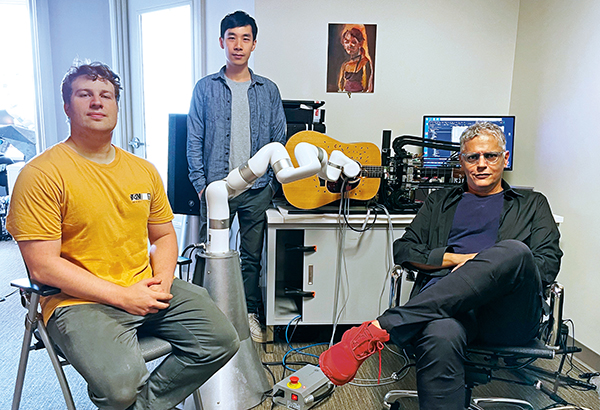

The paper’s authors, which also included Weinberg and Ph.D. student Amit Rogel, implemented their findings — the recording, the modeling, the mathematical representations of human expressivity — into their hardware and software design.

With the ERG assembled and ready to play music, they recruited 50 guitarists to take part in a survey (49 ultimately participated). These guitarists, of varying skill levels, listened to randomized blind audio samples, played by human guitarists, the robot, and a digital (MIDI) acoustic guitar. They were then asked to rate the expressivity of each sample.

In the strumming excerpts of this subjective exercise, the surveyed guitarists gave the human musicians a slightly higher rating. In the picking excerpts, the robot scored slightly higher. The MIDI samples finished a distant last in each exercise.

“We were encouraged to find that the ERG performed with human-level expressivity,” Yang said. “And we believe this technology could potentially be adapted to other string instruments.”

The robot can use picking techniques and play chords that transcend human abilities (it can play more than 1,000 different versions of the A-minor chord, for example), meaning the ERG can also play music unattainable by human guitarists.

But the aim, Weinberg said, is to augment the human experience, not replace it. “We are now starting to explore how the ERG could become an embodied performance companion for human musicians. Like all our robotic musicians, we want the ERG to be surprising and to be inspiring. We want it to help humans to play music differently and, hopefully, think about music in new ways.”

Photo captions (top to bottom):

- Ning Yang led development a robot guitarist as part of his final Ph.D. project in Gil Weinberg’s lab.

- Amit Rogel, Ning Yang, and Gil Weinberg collaborated on the ERG study.

CITATION: Yang, N., Rogel, A., Weinberg, G. “Design of an Expressive Robotic Guitarist.” IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters (2023).

Writer & Photos: Jerry Grillo

Video: Courtesy of the Robotic Musicianship Lab

Media Contact: Jerry Grillo | jerry.grillo@ibb.gatech.edu