From Galaxy to Ground: How Space Research Shapes Everyday Life

Georgia Tech space researchers’ work benefits Earth technologies, too.

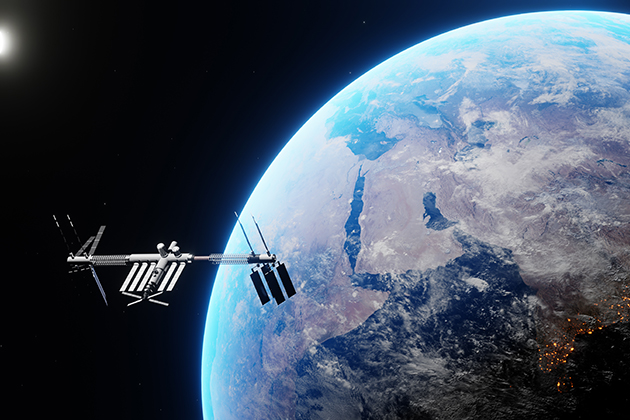

When we check the weather forecast, that information comes from satellites. When we FaceTime a friend, that call could come via satellites. From cellphone networks to national security systems, satellites are vital to our connected globe. Yet regulating how satellites function across borders is almost as complicated as the technology that launches them into space. Researchers in Georgia Tech’s Space Research Institute are shaping how satellites operate, both scientifically and politically.

Satellites aren’t the only technology Georgia Tech applies to terrestrial problems. Researchers are using gravity experiments to improve energy storage and are discovering lessons from science fiction. This Institute-wide work proves space isn’t the final frontier in paradigm-shifting research — it’s a bridge.

Reading Into Possibility

Lisa Yaszek

To imagine technology not just for our planet but the rest of the galaxy, scientists need inspiration. This is where Lisa Yaszek’s work comes in. As Regents’ Professor of Science Fiction Studies in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication (LMC), Yaszek studies how science fiction stories reflect and influence actual science and technology. To Yaszek, these are not mere stories.

“In the last 200 years, science fiction has become a common global language we can use to speak to each other across centuries, continents, and cultures,” she said.

This type of storytelling is also paramount for the scientific profession. Scientists need to tell compelling narratives and describe possible futures when writing grant applications. Science fiction or not, stories are fundamental. To that end, Yaszek has partnered with faculty members from the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) and the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School of Public Policy to examine how storytelling affects public understanding of nanoscience and technology. She has also hosted imagineering sessions for materials scientists, space researchers, and science fiction authors at local events and international conferences. Her expert commentary on science fiction as a window into scientific and technological history has appeared in numerous prominent publications.

“Science fiction is a genre that teaches students how to think through the potential impact of science and technology on people. I want my students to ask, ‘What are the steps you take to make that future happen?’” –Lisa Yaszek

She is currently collaborating with colleagues from LMC, the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, the School of Music, and the Office of Student Engagement on a grant-funded event series called “The Art of Failure.” This series brings together scientists, artists, and students to explore the role of failure in technoscientific progress, culminating in a student-centered art show.

Yaszek also shares her expertise with students in majors across the Institute, who often find that the futuristic characters they read about are grappling with issues similar to today’s. A biomedical engineering student focused her research on reproductive technology design after helping Yaszek compile a feminist science fiction anthology. The stories helped the student realize that reproductive health could be more affordable and male-friendly — and that she could contribute.

“This is a genre that teaches students how to think through the potential impact of science and technology on people,” Yaszek said. “I want my students to ask, ‘What are the steps you take to make that future happen?’”

Yaszek’s work is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Defying Gravity

Álvaro Romero-Calvo

Gravity isn’t an all-or-nothing state. Orbiting spacecraft experience microgravity, which is a near-weightless state. Astronauts bouncing off the lunar surface are subject to low gravity — 1/6th of the Earth's gravity. Because liquids and gases behave very differently in these environments, space engineers and astronauts need assurance that propulsion, life support, and thermal systems will behave as intended when gravity is turned off. In his lab, Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering (AE) Assistant Professor Álvaro Romero-Calvo studies how these and other substances behave in low-gravity conditions.

“I see microgravity as a magnifying glass that allows us to study fundamental physical phenomena of relevance to a wide range of technologies in space and on Earth,” he said.

One of these areas is renewable energy. Energy from weather-dependent sources like solar or wind power needs to be reliably and safely stored as these technologies become more prevalent. Hydrogen storage can help convert electric energy to chemical energy via water electrolysis, but keeping bubbles out of these cells is crucial, which is also a problem in microgravity environments.

Romero-Calvo’s research group uses parabolic flights that mimic microgravity conditions to test these bubbly flows. They are also constructing a drop tower — which will be available to the entire campus — to test how any object or system behaves when dropped while experiencing a microgravity environment.

“We are working very intensely to bring humans to the moon and Mars, but we are also developing technologies that can be used to produce hydrogen on Earth much more efficiently and much more reliably,” he said.

Just as gravity isn’t binary, neither is research intended for space. With Romero-Calvo’s work, humans in space and on land will benefit. His work is funded by NASA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and industry partners.

“We are working very intensely to bring humans to the moon and Mars, but we are also developing technologies that can be used to produce hydrogen on Earth much more efficiently and much more reliably.” –Álvaro Romero-Calvo

Propelling the Future

Mitchell Walker II

Satellites make our world run, but keeping them in orbit is trickier than it seems. Although satellites float in space, they’re still affected by what happens on Earth. A rainy season in Brazil can shift Earth’s gravity and disturb a satellite orbiting the planet. This is why researchers like Mitchell Walker II, the William R.T. Oakes Jr. School Chair in AE, study propulsion. Space propulsion, a method to accelerate spacecraft, ensures these satellites stay in the correct orbit.

At its most basic, Walker’s research focuses on the physics of plasma — ionized gas composed of electrons. Plasma physics helps propel satellites in space, and effectively harnessing a satellite’s electrical power is vital to keep satellite services operational. Walker’s research partners in the military, civilian, and commercial spaces need this knowledge to understand where they can put satellites and how close together, particularly as space gets more crowded.

“Every time something in space propulsion research changes, it pushes us to a new application and new regime for physics,” Walker said.

Infrastructure to keep satellites in orbit and to maintain a presence on the moon or Mars is becoming increasingly vital. Walker sees this moment as an inflection point in the space economy, comparing it to when railroads finally connected the West and East Coasts of the U.S. in the 19th century. The railroads helped send supplies and build out the West Coast, and propulsion will have a similar advantage for space. Whoever can get the most satellites in orbit — and keep them there — will have the advantage.

Walker’s work is funded by NASA, the Air Force, and industry partners.

Keeping Space Safe

Thomas González Roberts

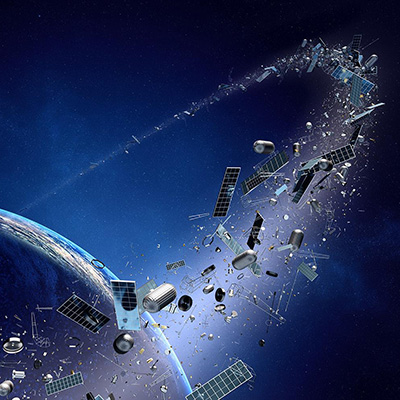

Space may seem infinite, but there are limits. How countries decide where to send satellites is a crucial international affairs issue. Not only does the physical location of a satellite matter, but so do the radio frequencies it emits to ensure clear communication. Like any domain, space needs policies for safety and fair use.

“The space domain is the newest of the physical domains, and it's ripe for geopolitical conflict,” said Thomas González Roberts, an assistant professor in the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs and AE. “Space systems already enable ground, air, and sea conflict, but there's never been a foreign state satellite attack after which that state claimed responsibility — yet.”

Roberts studies how to prevent space conflict and mitigate the damage if tensions rise. He pursues this from technical aspects, such as characterizing space systems’ vulnerabilities to disruption and degradation. He also looks at political aspects, like a country starting an arms race in space. Roberts wants to train engineers, who can already answer technical questions, to influence space policy. His students often analyze raw satellite data to detect satellite motion and predict their behavior.

“A better world is one in which we have a secure space domain that's free from international geopolitical conflict,” Roberts said.

“A better world is one in which we have a secure space domain that's free from international geopolitical conflict.” –Thomas González Roberts

Satellite Spatial Awareness

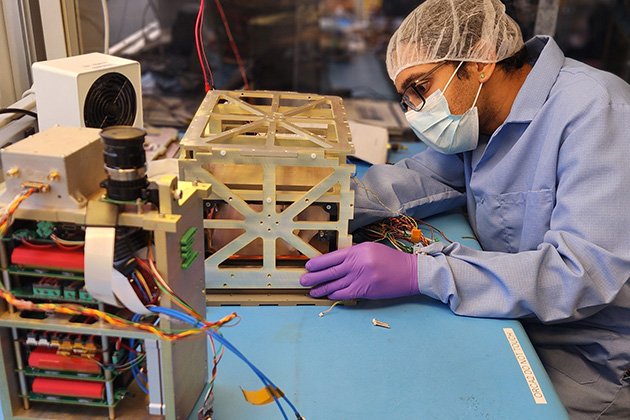

Surya Venkatram, the student lead for OrCa2, putting some final touches on the OrCa2 satellite.

Legislating satellite trajectories in policy is one thing, but ensuring they have clear paths in space is another. Brian Gunter, an associate professor in AE, leads the Orbital Calibration 2 Mission (OrCa2) satellite mission. OrCa2’s goal is to send two small satellites, called CubeSats, into space. These CubeSats have special reflective panels that can be used to develop improved methods for tracking space objects. One of the satellites (OrCa2a) also carries a camera that will track other space objects from orbit, including the second OrCa2 satellite (OrCa2b). This mission is designed to accurately track space objects so that future collisions between space objects (like debris and other satellites) can be avoided.

“This project is all about space domain awareness,” Gunter said, “providing space object tracking information in an effort to improve space traffic coordination and reduce the collision risk of current and future space object populations.”

Gunter’s research is funded by NASA, the Aerospace Corporation, and GTRI’s independent research and development programs.

Sharing Satellites’ Savvy

Mariel Borowitz

When we think of satellites, we often envision them taking photos of landscapes, but satellites can also give up-to-date information on resource allocation: What crops are stressed? What areas have groundwater? Where are populations in underserved areas? All of this information can be vital to policy decisions, but only if everyone has access to it.

Earth observation satellites are constantly collecting data, but who has access to that data? NASA’s data is public, but most private companies — and even some other countries — don’t widely share their information. Mariel Borowitz, associate professor in the Nunn School of International Affairs, studies satellite data transparency to understand how the open availability of information benefits from satellite programs.

“No one entity can collect all the data we need to understand complex issues like climate change,” Borowitz said. “When data is shared openly, we can improve global understanding.”

Borowitz has researched the benefits this shared data can have for society. Working with the Gates Foundation, she examined a case in which satellite data helped provide more accurate population maps. These maps enabled polio vaccination teams to find previously underserved populations in Nigeria, accelerating the effort to eradicate polio and resulting in millions of dollars in cost savings. With appropriate transparency, satellites can collect data that could change the world for the better.

Borowitz’s research is funded by the NSF and NASA.

Writer and Media Contact: Tess Malone | tess.malone@gatech.edu

Copy Editor: Stacy Braukman

Photos: Adobe Stock and Courtesy of Georgia Tech

Space Traffic and Trash: Policy Experts Work Toward a Sustainable Final Frontier

Space Traffic and Trash: Policy Experts Work Toward a Sustainable Final Frontier Georgia Tech Study Hopes to Prevent Cislunar Collisions as Moon Missions Increase

Georgia Tech Study Hopes to Prevent Cislunar Collisions as Moon Missions Increase Georgia Tech Opens New Aircraft Prototyping Laboratory

Georgia Tech Opens New Aircraft Prototyping Laboratory