Yongsheng Chen Awarded $300K Grant for Sustainable Agriculture AI Research

May 23, 2024 —

Yongsheng Chen, Bonnie W. and Charles W. Moorman IV Professor in Georgia Tech's School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, has been awarded a $300,000 National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to spearhead efforts to enhance sustainable agriculture practices using innovative AI solutions.

The collaborative project, named EAGER: AI4OPT-AG: Advancing Quad Collaboration via Digital Agriculture and Optimization, is a joint effort initiated by Georgia Tech in partnership with esteemed institutions in Japan, Australia, and India. The project aims to drive advancements in digital agriculture and optimization, ultimately supporting food security for future generations.

Chen, who also leads the Urban Sustainability and Resilience Thrust for the NSF Artificial Intelligence Research Institute for Advances in Optimization (AI4OPT), is excited about this new opportunity. "I am thrilled to lead this initiative, which marks a significant step forward in harnessing artificial intelligence (AI) to address pressing issues in sustainable agriculture," he said.

Highlighting the importance of AI in revolutionizing agriculture, Chen explained, "AI enables swift, accurate, and non-destructive assessments of plant productivity, optimizes nutritional content, and enhances fertilizer usage efficiency. These advancements are crucial for mitigating agriculture-related greenhouse gas emissions and solving climate change challenges."

To read the full agreement, click here.

Breon Martin

AI Research Communications Manager

Georgia Tech

Family Loss Brings About Medical Breakthrough

May 14, 2024 —

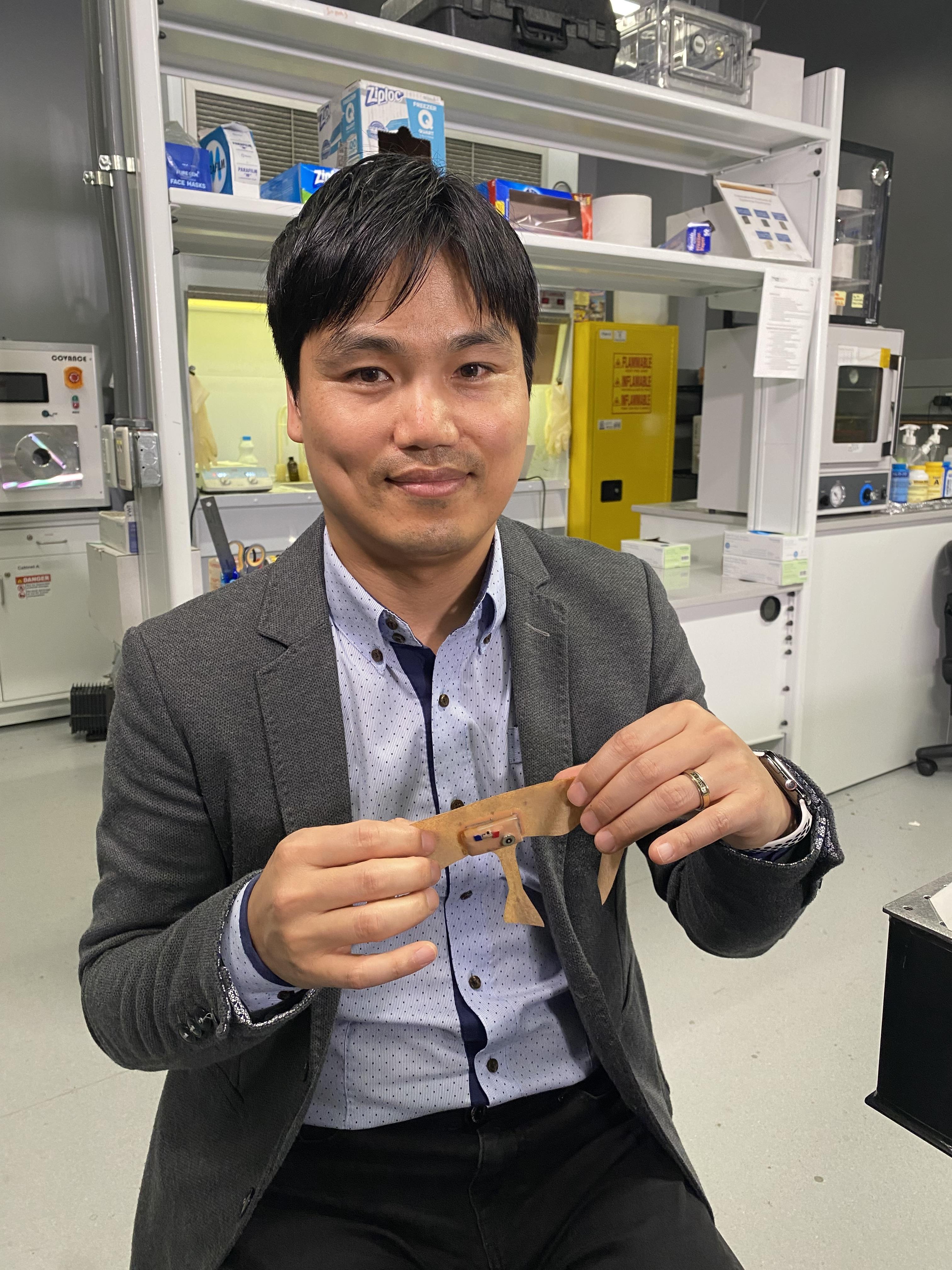

Hong Yeo shows off the latest version of his wearable sleep monitoring device.

The call from his mom is still vivid 20 years later. Moments this big and this devastating can define lives, and for Hong Yeo, today a Georgia Tech mechanical engineer, this call certainly did. Yeo was a 21-year-old in college studying car design when his mom called to tell him his father had died in his sleep. A heart attack claimed the life of the 49-year-old high school English teacher who had no history of heart trouble and no signs of his growing health threat. For the family, it was a crushing blow that altered each of their paths.

“It was an uncertain time for all of us,” said Yeo. “This loss changed my focus.”

For Yeo, thoughts and dreams of designing cars for Hyundai in Korea turned instead toward medicine. The shock of his father going from no signs of illness to gone forever developed into a quest for medical answers that might keep other families from experiencing the pain and loss his family did — or at least making it less likely to happen.

Yeo’s own research and schooling in college pointed out a big problem when it comes to issues with sleep and how our bodies’ systems perform — data. He became determined to invent a way to give medical doctors better information that would allow them to spot a problem like his father’s before it became life-threatening.

His answer: a type of wearable sleep data system. Now very close to being commercially available, Yeo’s device comes after years of working on the materials and electronics for an easy-to-wear, comfortable mask that can gather data about sleep over multiple days or even weeks, allowing doctors to catch sporadic heart problems or other issues. Different from some of the bulky devices with straps and cords currently available for at-home heart monitoring, it offers the bonuses of ease of use and comfort, ensuring little to no alteration to users’ bedtime routine or wear. This means researchers can collect data from sleep patterns that are as close to normal sleep as possible.

“Most of the time now, gathering sleep data means the patient must come to a lab or hospital for sleep monitoring. Of course, it’s less comfortable than home, and the devices patients must wear make it even less so. Also, the process is expensive, so it’s rare to get multiple nights of data,” says Audrey Duarte, University of Texas human memory researcher.

Duarte has been working with Yeo on this system for more than 10 years. She says there are so many mental and physical health outcomes tied to sleep that good, long-term data has the potential to have tremendous impact.

“The results we’ve seen are incredibly encouraging, related to many things —from heart issues to areas I study more closely like memory and Alzheimer’s,” said Duarte.

Yeo’s device may not have caught the arrhythmia that caused his father’s heart attack, but nights or weeks of data would have made effective medical intervention much more likely.

Inspired by his own family’s loss, Yeo’s life’s work has become a tool of hope for others.

Blair.Meeks@gatech.edu

This Modified Stainless Steel Could Kill Bacteria Without Antibiotics or Chemicals

May 20, 2024 —

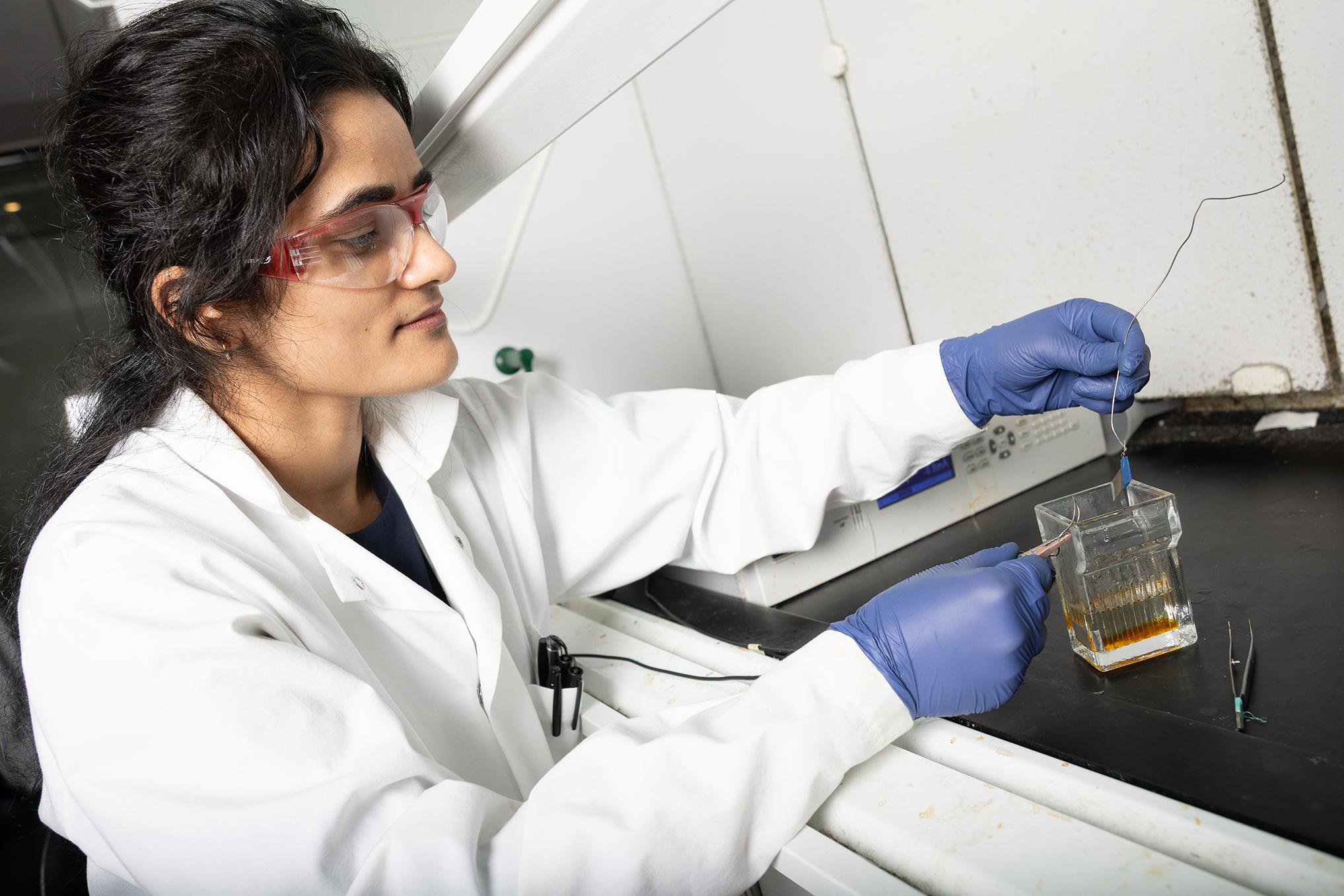

Postdoctoral scholar Anuja Tripathi examines a small sample of stainless steel after an electrochemical etching process she designed to create nano-scale needle-like structures on its surface. A second process deposits copper ions on the surface to create a dual antibacterial material. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

An electrochemical process developed at Georgia Tech could offer new protection against bacterial infections without contributing to growing antibiotic resistance.

The approach capitalizes on the natural antibacterial properties of copper and creates incredibly small needle-like structures on the surface of stainless steel to kill harmful bacteria like E. coli and Staphylococcus. It’s convenient and inexpensive, and it could reduce the need for chemicals and antibiotics in hospitals, kitchens, and other settings where surface contamination can lead to serious illness.

It also could save lives: A global study of drug-resistant infections found they directly killed 1.27 million people in 2019 and contributed to nearly 5 million other deaths — making these infections one of the leading causes of death for every age group.

Researchers described the copper-stainless steel and its effectiveness May 20 in the journal Small.

Joshua Stewart

College of Engineering

From Roots to Resilience: Investigating the Vital Role of Microbes in Coastal Plant Health

May 15, 2024 — Atlanta, GA

Georgia Tech researchers surveying field sites in the salt marshes of Sapelo Island, Georgia.

Georgia’s saltwater marshes — living where the land meets the ocean — stretch along the state’s entire 100-mile coastline. These rich ecosystems are largely dominated by just one plant: grass.

Known as cordgrass, the plant is an ecosystem engineer, providing habitats for wildlife, naturally cleaning water as it moves from inland to the sea, and holding the shoreline together so it doesn’t collapse. Cordgrass even protects human communities from tidal surges.

Understanding how these plants stay healthy is of crucial ecological importance. For example, one known plant stressor prevalent in marsh soils is the dissolved sulfur compound, sulfide, which is produced and consumed by bacteria. But while the Georgia coastline boasts a rich tradition of ecological research, understanding the nuanced ways bacteria interact with plants in these ecosystems has been elusive. Thanks to recent advances in genomic technology, Georgia Tech biologists have begun to reveal never-before-seen ecological processes.

The team’s work was published in Nature Communications.

Joel Kostka, the Tom and Marie Patton Distinguished Professor and associate chair for Research in the School of Biological Sciences, and Jose Luis Rolando, a postdoctoral fellow, set out to investigate the relationship between the cordgrass Spartina alterniflora and the microbial communities that inhabit their roots, identifying the bacteria and their roles.

“Just like humans have gut microbes that keep us healthy, plants depend on microbes in their tissues for health, immunity, metabolism, and nutrient uptake,” Kostka said. “While we’ve known about the reactions that drive nutrient and carbon cycling in the marsh for a long time, there’s not as much data on the role of microbes in ecosystem functioning.”

Out in the Marsh

A major way that plants get their nutrients is through nitrogen fixation, a process in which bacteria convert nitrogen into a form that plants can use. In marshes, this role has mostly been attributed to heterotrophs, or bacteria that grow and get their energy from organic carbon. Bacteria that consume the plant toxin sulfide are chemoautotrophs, using energy from sulfide oxidation to fuel the uptake of carbon dioxide to make their own organic carbon for growth.

“Through previous work, we knew that Spartina alterniflora has sulfur bacteria in its roots and that there are two types: sulfur-oxidizing bacteria, which use sulfide as an energy source, and sulfate reducers, which respire sulfate and produce sulfide, a known toxin for plants,” Rolando said. “We wanted to know more about the role these different sulfur bacteria play in the nitrogen cycle.”

Kostka and Rolando headed to Sapelo Island, Georgia, where they have regularly conducted fieldwork in the salt marshes. Wading into the marsh, shovels and buckets in hand, the researchers and their students collected cordgrass along with the muddy sediment samples that cling to their roots. Back at the field lab, the team gathered around a basin filled with creek water and carefully washed the grass, gently separating the plant roots.

Next, they used a special technique involving heavier versions of chemical elements that occur in nature as tracers to track the microbial processes. They also analyzed the DNA and RNA of the microbes living in different compartments of the plants.

Using a sequencing technology known as shotgun metagenomics, they were able to retrieve the DNA from the whole microbial community and reconstruct genomes from newly discovered organisms. Similarly, untargeted RNA sequencing of the microbial community allowed them to assess which microbial species and specific functions were active in close association with plant roots.

Using this combination of techniques, they found that chemoautotrophic sulfur-oxidizing bacteria were also involved in nitrogen fixation. Not only did these bacteria help plants by detoxifying the root zone, but they also played a crucial role in providing nitrogen to the plants. This dual role of the bacteria in sulfur cycling and nitrogen fixation highlights their importance in coastal ecosystems and their contribution to plant health and growth.

"Plants growing in areas with high levels of sulfide accumulation tend to be smaller and less healthy," said Rolando. "However, we found that the microbial communities within Spartina roots help to detoxify the sulfide, enhancing plant health and resilience."

Local to Global Significance

Cordgrasses aren’t just the main player in Georgia marshes; they also dominate marsh landscapes across the entire Southeast, including the Carolinas and the Gulf Coast. Moreover, the researchers found that the same bacteria are associated with cordgrass, mangrove, and seagrass roots in coastal ecosystems across the planet.

"Much of the shoreline in tropical and temperate climates is covered by coastal wetlands,” Rolando said. “These areas likely harbor similar microbial symbioses, which means that these interactions impact ecosystem functioning on a global scale."

Looking ahead, the researchers plan to further explore the details of how marsh plants and microbes exchange nitrogen and carbon, using state-of-the-art microscopy techniques coupled with ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry to confirm their findings at the single-cell level.

"Science follows technology, and we were excited to use the latest genomic methods to see which types of bacteria were there and active,” Kostka said. “There's still much to learn about the intricate relationships between plants and microbes in coastal ecosystems, and we are beginning to uncover the extent of the microbial complexity that keeps marshes healthy.”

Citation: Rolando, J.L., Kolton, M., Song, T. et al. Sulfur oxidation and reduction are coupled to nitrogen fixation in the roots of the salt marsh foundation plant Spartina alterniflora. Nat Commun 15, 3607 (2024).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47646-1

Funding: This work was supported in part by an institutional grant (NA18OAR4170084) to the Georgia Sea Grant College Program from the National Sea Grant Office, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, US Department of Commerce, and by a grant from the National Science Foundation (DEB 1754756).

Joel Kostka, the Tom and Marie Patton Distinguished Professor and associate chair for Research in the School of Biological Sciences.

Georgia Tech postdoctoral fellow Jose Rolando (right) and graduate student Gabrielle Krueger prepare samples for chemical analysis in the field at Sapelo Island, Georgia.

Researchers washing cordgrass roots for microbial analysis.

Georgia Tech graduate student Tianze Song collects porewater samples for chemical analysis in the marsh on Sapelo Island, Georgia.

Catherine Barzler, Senior Research Writer/Editor

From Brewery to Biofilter: Making Yeast-Based Water Purification Possible

May 15, 2024 — Atlanta, GA

When looking for an environmentally friendly and cost-effective way to clean up contaminated water and soil, Georgia Tech researchers Patricia Stathatou and Christos Athanasiou turned to yeast. A cheap byproduct from fermentation processes — e.g., something your local brewery discards in mass quantities after making a batch of beer — yeast is widely known as an effective biosorbent. Biosorption is a mass transfer process by which an ion or molecule binds to inactive biological materials through physicochemical interactions.

When they initially studied this process, Stathatou and Athanasiou found that yeast can effectively and rapidly remove trace lead — at challenging initial concentrations below one part per million — from drinking water. Conventional water treatment methods either fail to eliminate lead at these low levels or result in high financial and environmental costs to do so. In a paper published today in RSC Sustainability, the researchers show how this process can be scaled.

“If you put yeast directly into water to clean it, you will need an additional treatment step to remove the yeast from the water afterward,” said Stathatou, a research scientist at the Renewable Bioproducts Institute and an incoming assistant professor at the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. “To implement this process at scale without requiring additional separation steps, the yeast cells need a housing.”

“Additionally, because yeast is abundant— in some cases, brewers even pay companies to haul it away as a waste byproduct — this process gives the yeast a second life,” said Athanasiou, an assistant professor in the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering. “It’s a plentiful low, or even negative, value resource, making this purification process inexpensive and scalable.”

To develop a housing for the yeast, Stathatou and Athanasiou partnered with MIT chemical engineers Devashish Gokhale and Patrick S. Doyle. Gokhale and Stathatou are the lead authors of this new study that demonstrates the yeast water purification process’s scalability.

“We decided to make these hollow capsules— analogous to a multivitamin pill — but instead of filling them up with vitamins, we fill them up with yeast cells,” Gokhale said. “These capsules are porous, so the water can go into the capsules and the yeast are able to bind all of that lead, but the yeast themselves can’t escape into the water.”

The yeast-laden capsules are sufficiently large, about half a millimeter in diameter, for easy separation from water by gravity. This means they can be used to make packed-bed bioreactors or biofilters, with contaminated water flowing through these hydrogel-encased yeast cells and coming out clean.

Stathatou and Athanasiou envision using these hydrogel yeast capsules in small biofilters consumers can put on their kitchen faucets, or biofilters large enough to fit municipal or industrial wastewater treatment systems. But to enable such scalability, the yeast-laden capsules’ ability to withstand the force generated by water flowing inside such systems needed to be studied as well.

To determine this, Athanasiou tested the capsules’ mechanical robustness, which is how strong and sturdy they are in the presence of waterflow forces. He found they can withstand forces like those generated by water running from a faucet, or even flows like those in water treatment plants that serve a few hundred homes. “In previous attempts to scale up biosorption with similar approaches, lack of mechanical robustness has been a common cause of failure,” Athanasiou said. “We wanted to make sure our work addressed this issue from the very beginning to ensure scalability.”

“After assessing the mechanical robustness of the yeast-laden capsules, we made a prototype biofilter using a 10-ml syringe,” Stathatou explained. “The initial lead concentration of water entering the biofilter was 100 parts per billion; we demonstrated that the biofilter could treat the contaminated water, meeting EPA drinking water guidelines, while operating continuously for 12 days.”

The researchers hope to identify ways to isolate and collect specific contaminants left behind in the filtering yeast, so those too can be used for other purposes.

“Apart from lead, which is widely used in systems for energy generation and storage, this process could be used to remove and recover other metals and rare earth elements as well,” Athanasiou said. “This process could even be useful in space mining or other space applications.”

They also would like to find a way to keep reusing the yeast. “But even if we can’t reuse yeast indefinitely, it is biodegradable,” Stathatou noted. “It doesn’t need to be put into an industrial composter or sent to a landfill. It can be left on the ground, and the yeast will naturally decompose over time, contributing to nutrient cycling.”

This circular approach aims to reduce waste and environmental impact, while also creating economic opportunities in local communities. Despite numerous lead contamination incidents across the U.S., the team’s successful biosorption method notably could benefit low-income areas historically burdened by pollution and limited access to clean water, offering a cost-effective remediation solution. “We think there’s an interesting environmental justice aspect to this, especially when you start with something as low-cost and sustainable as yeast, which is essentially available anywhere,” Gokhale says.

Moving forward, Stathatou and Athanasiou are exploring other uses for their hydrogel-yeast purification method. The researchers are optimistic that, with modifications, this process can be used to remove additional inorganic and organic contaminants of emerging concern, such as PFAS — or “forever” chemicals — from the water or the ground.

Citation: Devashish Gokhale, Patritsia M. Stathatou, Christos E. Athanasiou, and Patrick S. Doyle, “Yeast-laden Hydrogel Capsules for Scalable Trace Lead Removal from Water,” RSC Sustainability.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/D4SU00052H

Funding: Patricia Stathatou was supported by funding from the Renewable Bioproducts Institute at Georgia Tech. Devashish Gokhale was supported by the Rasikbhai L. Meswani Fellowship for Water Solutions and the MIT Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food Systems Lab (J-WAFS).

Shelley Wunder-Smith

Family Loss Brings About Medical Breakthrough

May 14, 2024 —

When he was in college, Hong Yeo's father died in his sleep from a heart attack, and Yeo changed his academic and research efforts as a result. Now, he and his research collaborators have developed a device that monitors vital signs during sleep, and it's the type of thing that may have helped doctors intervene in his father's illness if it had been available. This Sleep Scan device is a type of mask you can easily take on and off, and it has now been tested with human subjects and is close to being available commercially.

The call from his mom is still vivid 20 years later. Moments this big and this devastating can define lives, and for Hong Yeo, today a Georgia Tech mechanical engineer, this call certainly did. Yeo was a 21-year-old in college studying car design when his mom called to tell him his father had died in his sleep. A heart attack claimed the life of the 49-year-old high school English teacher who had no history of heart trouble and no signs of his growing health threat. For the family, it was a crushing blow that altered each of their paths.

“It was an uncertain time for all of us,” said Yeo. “This loss changed my focus.”

For Yeo, thoughts and dreams of designing cars for Hyundai in Korea turned instead toward medicine. The shock of his father going from no signs of illness to gone forever developed into a quest for medical answers that might keep other families from experiencing the pain and loss his family did — or at least making it less likely to happen.

Yeo’s own research and schooling in college pointed out a big problem when it comes to issues with sleep and how our bodies’ systems perform — data. He became determined to invent a way to give medical doctors better information that would allow them to spot a problem like his father’s before it became life-threatening.

His answer: a type of wearable sleep data system. Now very close to being commercially available, Yeo’s device comes after years of working on the materials and electronics for an easy-to-wear, comfortable mask that can gather data about sleep over multiple days or even weeks, allowing doctors to catch sporadic heart problems or other issues. Different from some of the bulky devices with straps and cords currently available for at-home heart monitoring, it offers the bonuses of ease of use and comfort, ensuring little to no alteration to users’ bedtime routine or wear. This means researchers can collect data from sleep patterns that are as close to normal sleep as possible.

“Most of the time now, gathering sleep data means the patient must come to a lab or hospital for sleep monitoring. Of course, it’s less comfortable than home, and the devices patients must wear make it even less so. Also, the process is expensive, so it’s rare to get multiple nights of data,” says Audrey Duarte, University of Texas human memory researcher.

Duarte has been working with Yeo on this system for more than 10 years. She says there are so many mental and physical health outcomes tied to sleep that good, long-term data has the potential to have tremendous impact.

“The results we’ve seen are incredibly encouraging, related to many things —from heart issues to areas I study more closely like memory and Alzheimer’s,” said Duarte.

Yeo’s device may not have caught the arrhythmia that caused his father’s heart attack, but nights or weeks of data would have made effective medical intervention much more likely.

Inspired by his own family’s loss, Yeo’s life’s work has become a tool of hope for others.

Hong Yeo’s father, Yonghyun Yeo, with his mother in Korea.

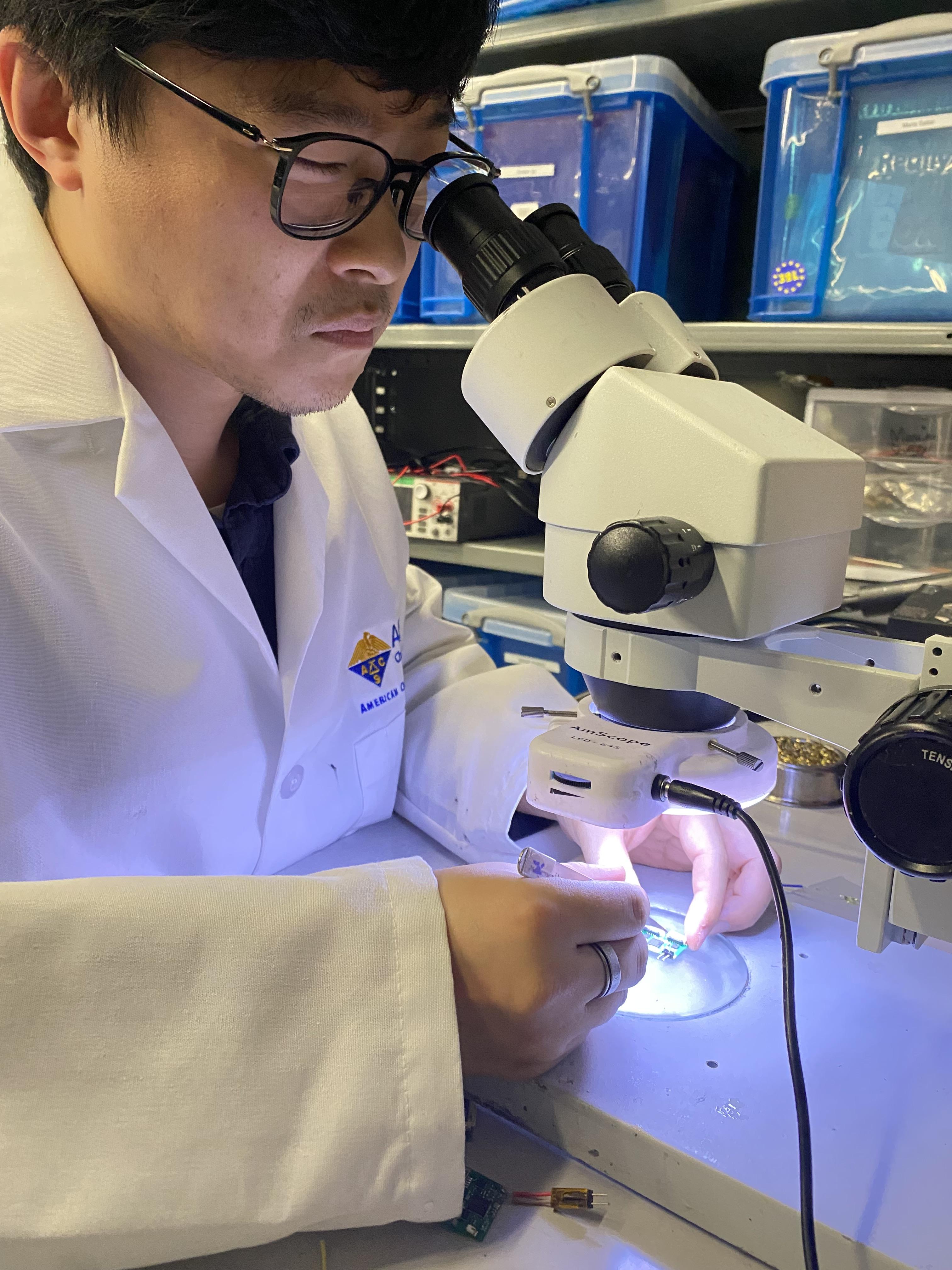

Taewoog Kang, a post-doctoral student in mechanical engineering, works to repair a tiny circuit in Hong Yeo’s lab on Georgia Tech’s campus.

Flicker Stimulation Shines in Clinical Trial for Epilepsy

May 09, 2024 —

A scientist and her tools: Annabelle Singer has quantified her flicker technology with unprecedented precision in a new clinical trial. — Photo by Jerry Grillo

Biomedical engineer Annabelle Singer has spent the past decade developing a noninvasive therapy for Alzheimer’s disease that uses flickering lights and rhythmic tones to modulate brain waves. Now she has discovered that the technique, known as flicker, also could benefit patients with a host of other neurological disorders, from epilepsy to multiple sclerosis.

Previously, Singer and her collaborators demonstrated that the lights and sounds, delivered to patients through goggles and headphones, have beneficial effects. Flicker has been successful in animal studies and in early human feasibility trials, where it was tested for safety, tolerance, and patient adherence.

Now, thanks to a clinical trial for people with epilepsy, the researchers quantified flicker’s effects with unprecedented precision. They also made an unexpected, but encouraging, discovery: The treatment reduced interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs) in the brain.

These large, intermittent electrophysiological events are observed between seizures in people with epilepsy. They appear as sharp spikes on an EEG readout.

“What’s interesting about these IEDs is that they don’t just occur in epilepsy,” said Singer, McCamish Foundation Early Career Professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. “They occur in autism, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and other neurological disorders, too.” And IEDs disrupt normal brain function, causing memory impairment.

Singer and her team published their findings recently in Nature Communications.

The Rhythm in Our Heads

Inside the brain are elaborate symphonies of electrical activity: brain waves, or oscillations, that compose our memories, thoughts, and emotions. Singer wants to modulate those oscillations for therapeutic purposes.

At specific frequencies of light and sound, the flicker treatment can induce gamma oscillations in mice. This helps the brain recruit microglia, cells responsible for removing beta amyloid, which is believed to play a central role in Alzheimer’s pathology. Part of the work is in recording what’s happening in the brain during treatment to verify how it’s working.

The patients in the trial were under the care of physician Jon Willie at the Emory University Hospital Epilepsy Monitoring Unit. (Willie, co-corresponding author of the study with Singer, is now at Washington University in St. Louis.) They were awaiting surgery to remove an area of the brain where seizures occur. Before that could happen, they had to undergo intracranial seizure monitoring — recording electrodes are placed in the brain to pinpoint the seizure onset zone and determine exactly which tissue should be removed. Then, patients and their care team wait for a seizure to happen. It can take days.

“In human studies, we’ve used noninvasive methods like functional MRI or scalp EEG, but they have real downsides in terms of resolution,” Singer said. “Working with these patients was a game changer. These are people with treatment-resistant epilepsy, which means that drugs aren’t working for them.”

Pathway to Healing

Singer’s team recruited 19 patients. Lead author of the study, Lou Blanpain, a former Ph.D. student in Singer’s lab and now a medical student at Emory, went from patient to patient with the flicker stimulation and recording equipment.

“Because these patients already had recording probes implanted for clinical reasons, we were able to record directly from the brain,” Singer said. “We’ve never been able to get recordings of this quality during flicker treatment before.”

As the researchers expected, flicker modulated the visual and auditory brain regions that respond strongly to stimuli. But it also reached deeper, into the medial temporal lobe and prefrontal cortex, brain regions crucial for memory. And across the brain, in regions Singer hadn’t fully explored before, she found IEDs were decreasing.

“That has important implications for whether flicker is therapeutically relevant for people with Alzheimer’s, but also in general if we want to target anything beyond the primary sensory regions,” she said. “All of this points to the potential use of flicker in a lot of different contexts. Going forward, we’re definitely going to look at other conditions and other potential implications.”

Citation: Lou T. Blanpain, Eric R. Cole, Emily Chen, James K. Park, Michael Y. Walelign, Robert E. Gross, Brian T. Cabaniss, Jon T. Willie, Annabelle C. Singer. “Multisensory Flicker Modulates Widespread Brain Networks and Reduces Interictal Epileptiform Discharges,” Nature Communications.

Funding: National Institutes of Health (R01 NS109226, RF1NS109226, RF1AG078736, R01 MH120194, P41 EB018783, MH12019), DARPA, McCamish Foundation, Packard Foundation.

Competing interests: Annabelle Singer owns shares in Cognito Therapeutics, which aims to develop gamma stimulation-related products. These conflicts are managed by Georgia Tech’s Office of Research Integrity Assurance.

Jerry Grillo

Tropical Revelations: Unearthing the Impacts of Hydrological Sensitivity on Global Rainfall

May 09, 2024 —

Jie He, assistant professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, wants to predict how rainfall will change in the presence of continuing climate change. — Photo by Jerry Grillo

Georgia Tech researcher Jie He set out to predict how rainfall will change as Earth’s atmosphere continues to heat up. In the process, he made some unexpected discoveries that might explain how greenhouse gas emissions will impact tropical oceans, affecting climate on a global scale.

“This is not a story with just one punch line,” said He, assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, whose most recent work appeared in the journal Nature Climate Change. “I didn’t really expect to find anything this interesting—there were a few surprises.”

He is principal investigator of the Climate Modeling and Dynamics Group, which combines expertise in physics, mathematics, and computer science to study climate change. The team’s latest study, a collaboration with Mississippi State University and Princeton University, examines hydrological sensitivity in the planet’s three tropical basins: the central portions of both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans and most of the Indian Ocean, an equatorial belt girding the Earth between the Tropic of Cancer (north) and Tropic of Capricorn (south).

Hydrological sensitivity (HS) refers to the precipitation change per degree of surface warming. Hydrological sensitivity is a key metric researchers use in evaluating or predicting how rainfall will respond to future climate change. Positive HS indicates a wetter climate, while negative HS indicates a drier climate.

“The projection of hydrological sensitivity and future precipitation has been widely investigated, but most studies look at global averages — nobody had yet looked closely at each individual basin,” He said. “And the real impact on global climate change will come from the regional scale.”

In other words, what happens in tropical waters has far-reaching effects.

Long Reach of the Tropics

He wanted to specifically examine the tropical basins because they already have a well-known influence on remote locations: El Niños and La Niñas. These weather patterns that shift every couple of years are examples of tropical oceanic precipitation changes that have a global impact.

“These precipitation changes create heating and cooling in the atmosphere that set off atmospheric waves affecting remote climates across the globe,” He said. During El Niño winters, for example, the southeastern U.S. typically gets more precipitation than usual.

But El Niños and La Niñas are naturally occurring, whereas the tropical precipitation changes He identified are projected as outcomes of human-induced global warming — a simulation, part of a climate model.

Climate models are an essential tool for He and other researchers, who use them to simulate possible future scenarios. These are computer programs that rely on complex math equations to project the atmospheric interactions of energy and matter likely to occur across the planet.

What surprised He was the substantial difference in HS between tropical basins. Essentially, in He’s model the Pacific tropical basin has an HS more than twice as large as the Indian basin, with the Atlantic basin projected as a negative value.

“It was surprising because these differences can’t be explained by the mainstream theories on tropical precipitation changes,” He said. “In other words, none of the theories we knew would have predicted it.”

Modeling the Sensitive Future

The effects of such diverging hydrological sensitivity would be widespread, according to He. For example, his experiments suggest that the continental U.S. will get wetter, and the Amazon will become drier.

“If these model projections are true, these effects will materialize as the climate continues to warm,” said He, who can’t predict exactly how long it will be before these effects can be detected in actual observations of our three-dimensional world.

That’s because they only have reliable observations of oceanic tropical precipitation since 1979. Precipitation changes over decades are strongly affected by internal climate variability — that is, climate change that isn’t caused by humans. When human-induced precipitation changes are significantly greater than internal climate variability, we should be able to detect the wide-ranging effects of diverging hydrological sensitivity.

But the challenges of continuing climate change do not allow the luxury of waiting until every aspect of climate projection becomes a reality, He noted, adding, “We are relying on climate projections to some extent to guide our adaptation and mitigation plans. Therefore, it is important to study and understand the climate projections.”

Based on the scenario projected by climate models used in He’s research, the effects of El Niños and La Niñas on remote climates will become stronger.

“What we can imply is that this strengthening would be partly due to the diverging HS among tropical basins,” He concluded.

While the future effects of HS on El Niños and La Niñas weren’t discussed in this study, He believes it would make a very interesting research subject going forward.

Advancing Careers of Interdisciplinary Research Faculty at Georgia Tech

May 08, 2024 —

Growing the careers of research faculty at Georgia Tech is an integral part of Research Next, the strategic plan for the Institute’s research enterprise.

Georgia Tech’s research faculty, who conduct vital research in labs, centers, and departments across campus, play a critical role in the research enterprise. To support these essential employees, Georgia Tech launched an initiative to recognize and develop its research faculty.

The Research Next team, now in the implementation phase of the plan, was tasked with finding ways to recognize, support, and retain research faculty. This included developing reference materials and workshops specifically designed to guide research faculty seeking promotions. These resources provide essential information on the advancement process, ensuring researchers are well-prepared to take the next step in their careers.

With this support and guidance, six researchers from the Interdisciplinary Research Institutes and other units reporting to the Vice President of Interdisciplinary Research applied for promotions. All six promotions were approved.

The following interdisciplinary researchers received promotions:

- Devin Brown, principal research engineer, Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology

- Michael Chang, principal research scientist, Brook Byers Institute for Sustainable Systems

- Paramita Chatterjee, research scientist II, Marcus Center for Therapeutic Cell Characterization and Manufacturing

- Evan Goldberg, principal research engineer, Laboratory for Synthetic Immunity and Global Center for Medical Innovation

- Vrinda Nandan, research scientist II, Design Intelligence Lab and the National AI Institute for Adult Learning and Online Education

- Sikka Harshvardhan, research scientist II, National AI Institute for Adult Learning and Online Education

In addition, the University System of Georgia’s Board of Regents has granted Leanne West, principal research scientist and the chief engineer of pediatric technologies at Georgia Tech, the prestigious distinction of Regents’ Researcher. As Chief Engineer, West coordinates research activities related to pediatrics across campus and serves as the technical liaison for the partnership with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

West’s research focuses on mobile and wireless health systems and sensor development, user interfaces, system integration, and diagnostic devices. She has seen her invention of a wireless personal captioning system installed at commercial venues through her start-up, Intelligent Access, LLC. She has another wearable system for identifying specific dog behaviors that has also reached the commercial market.

Laurie Haigh

Research Communications