The darkness that swept over the Venezuelan capital in the predawn hours of Jan. 3, 2026, signaled a profound shift in the nature of modern conflict: the convergence of physical and cyber warfare. While U.S. special operations forces carried out the dramatic seizure of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, a far quieter but equally devastating offensive was taking place in the unseen digital networks that help operate Caracas.

The blackout was not the result of bombed transmission towers or severed power lines but rather a precise and invisible manipulation of the industrial control systems that manage the flow of electricity. This synchronization of traditional military action with advanced cyber warfare represents a new chapter in international conflict, one where lines of computer code that manipulate critical infrastructure are among the most potent weapons.

To understand how a nation can turn an adversary’s lights out without firing a shot, you have to look inside the controllers that regulate modern infrastructure. They are the digital brains responsible for opening valves, spinning turbines and routing power.

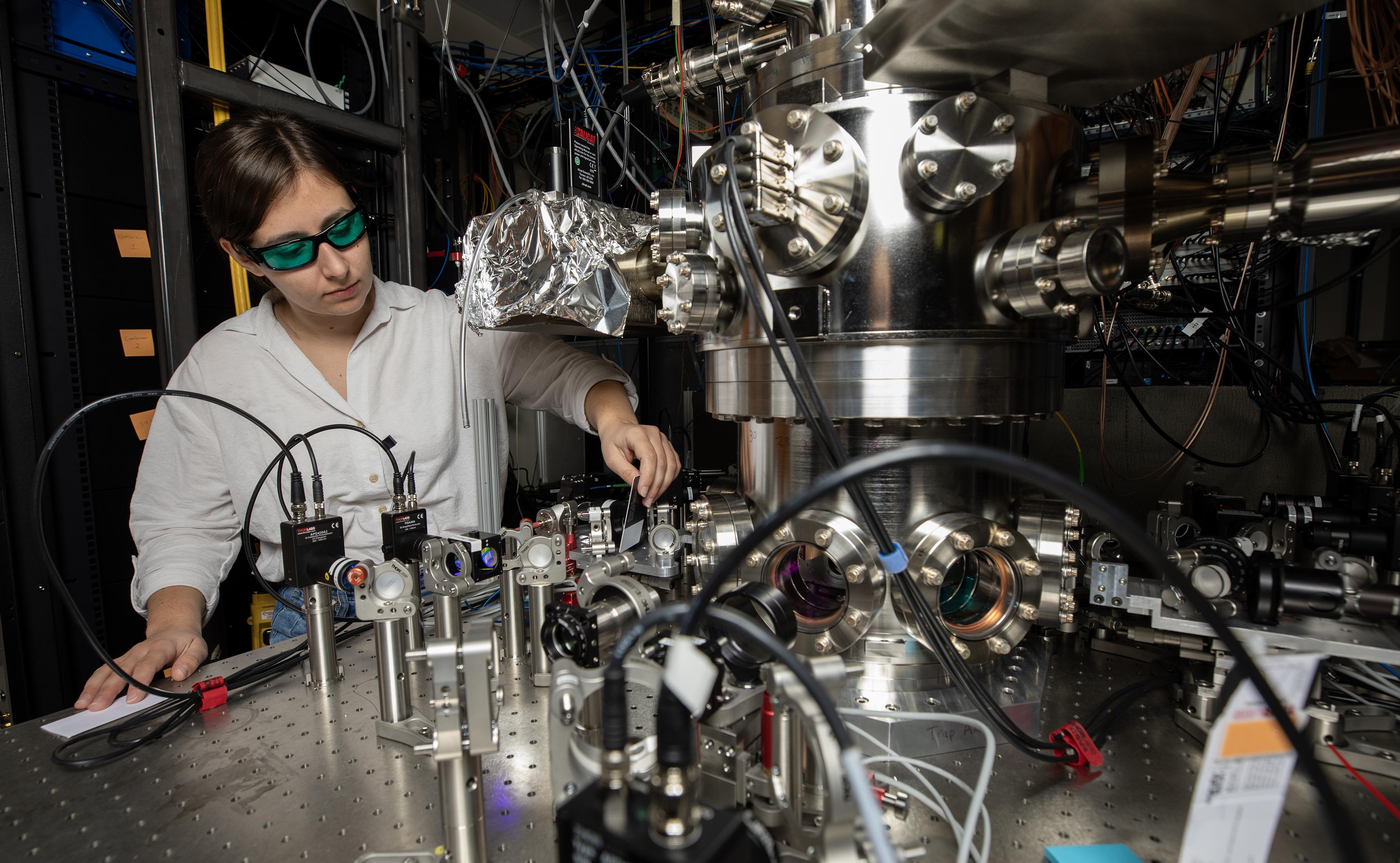

For decades, controller devices were considered simple and isolated. Grid modernization, however, has transformed them into sophisticated internet-connected computers. As a cybersecurity researcher, I track how advanced cyber forces exploit this modernization by using digital techniques to control the machinery’s physical behavior.

Hijacked Machines

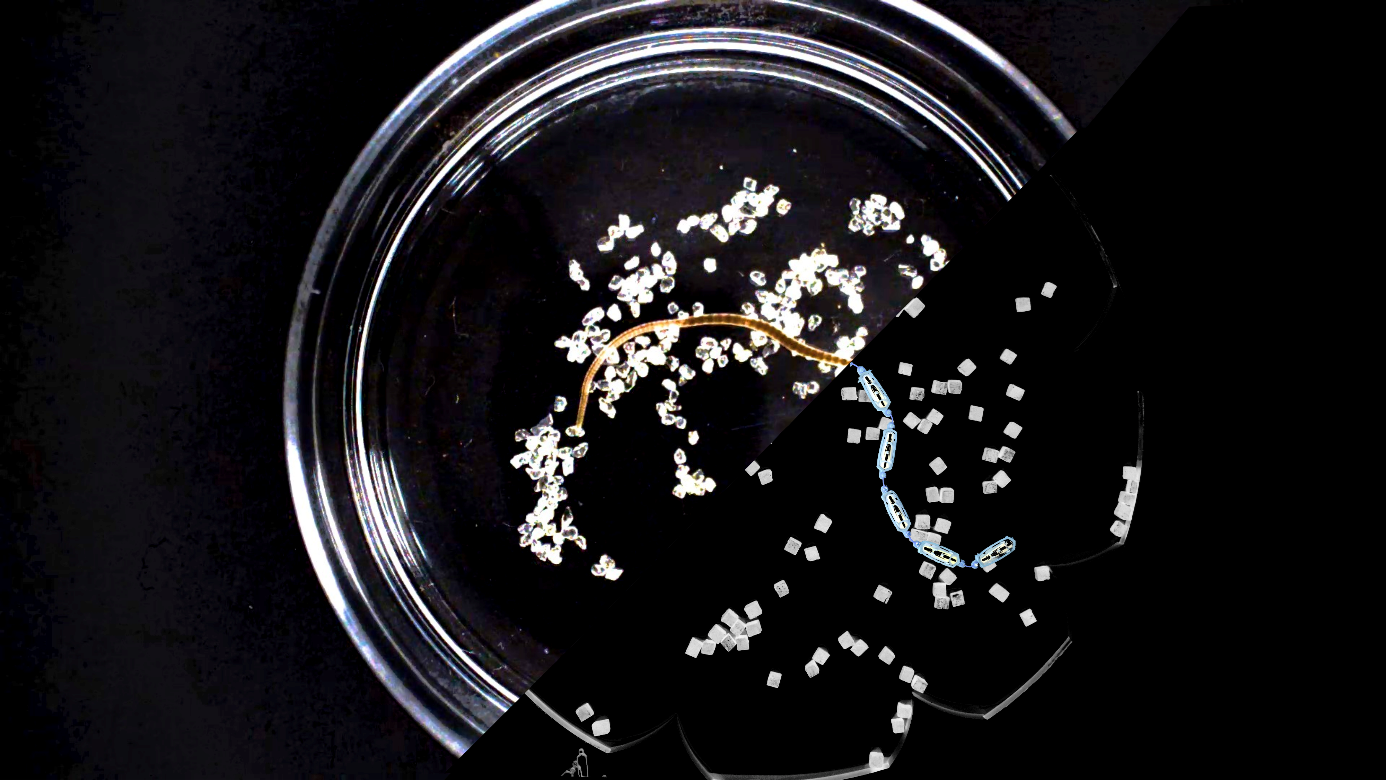

My colleagues and I have demonstrated how malware can compromise a controller to create a split reality. The malware intercepts legitimate commands sent by grid operators and replaces them with malicious instructions designed to destabilize the system.

For example, malware could send commands to rapidly open and close circuit breakers, a technique known as flapping. This action can physically damage massive transformers or generators by causing them to overheat or go out of sync with the grid. These actions can cause fires or explosions that take months to repair.

Simultaneously, the malware calculates what the sensor readings should look like if the grid were operating normally and feeds these fabricated values back to the control room. The operators likely see green lights and stable voltage readings on their screens even as transformers are overloading and breakers are tripping in the physical world. This decoupling of the digital image from physical reality leaves defenders blind, unable to diagnose or respond to the failure until it is too late.

Historical examples of this kind of attack include the Stuxnet malware that targeted Iranian nuclear enrichment plants. The malware destroyed centrifuges in 2009 by causing them to spin at dangerous speeds while feeding false “normal” data to operators.

Another example is the Industroyer attack by Russia against Ukraine’s energy sector in 2016. Industroyer malware targeted Ukraine’s power grid, using the grid’s own industrial communication protocols to directly open circuit breakers and cut power to Kyiv.

More recently, the Volt Typhoon attack by China against the United States’ critical infrastructure, exposed in 2023, was a campaign focused on pre-positioning. Unlike traditional sabotage, these hackers infiltrated networks to remain dormant and undetected, gaining the ability to disrupt the United States’ communications and power systems during a future crisis.

To defend against these types of attacks, the U.S. military’s Cyber Command has adopted a “defend forward” strategy, actively hunting for threats in foreign networks before they reach U.S. soil.

Domestically, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency promotes “secure by design” principles, urging manufacturers to eliminate default passwords and utilities to implement “zero trust” architectures that assume networks are already compromised.

Supply Chain Vulnerability

Nowadays, there is a vulnerability lurking within the supply chain of the controllers themselves. A dissection of firmware from major international vendors reveals a significant reliance on third-party software components to support modern features such as encryption and cloud connectivity.

This modernization comes at a cost. Many of these critical devices run on outdated software libraries, some of which are years past their end-of-life support, meaning they’re no longer supported by the manufacturer. This creates a shared fragility across the industry. A vulnerability in a single, ubiquitous library like OpenSSL – an open-source software toolkit used worldwide by nearly every web server and connected device to encrypt communications – can expose controllers from multiple manufacturers to the same method of attack.

Modern controllers have become web-enabled devices that often host their own administrative websites. These embedded web servers present an often overlooked point of entry for adversaries.

Attackers can infect the web application of a controller, allowing the malware to execute within the web browser of any engineer or operator who logs in to manage the plant. This execution enables malicious code to piggyback on legitimate user sessions, bypassing firewalls and issuing commands to the physical machinery without requiring the device’s password to be cracked.

The scale of this vulnerability is vast, and the potential for damage extends far beyond the power grid, including transportation, manufacturing and water treatment systems.

Using automated scanning tools, my colleagues and I have discovered that the number of industrial controllers exposed to the public internet is significantly higher than industry estimates suggest. Thousands of critical devices, from hospital equipment to substation relays, are visible to anyone with the right search criteria. This exposure provides a rich hunting ground for adversaries to conduct reconnaissance and identify vulnerable targets that serve as entry points into deeper, more protected networks.

The success of recent U.S. cyber operations forces a difficult conversation about the vulnerability of the United States. The uncomfortable truth is that the American power grid relies on the same technologies, protocols and supply chains as the systems compromised abroad.

Regulatory Misalignment

The domestic risk, however, is compounded by regulatory frameworks that struggle to address the realities of the grid. A comprehensive investigation into the U.S. electric power sector my colleagues and I conducted revealed significant misalignment between compliance with regulations and actual security. Our study found that while regulations establish a baseline, they often foster a checklist mentality. Utilities are burdened with excessive documentation requirements that divert resources away from effective security measures.

This regulatory lag is particularly concerning given the rapid evolution of the technologies that connect customers to the power grid. The widespread adoption of distributed energy resources, such as residential solar inverters, has created a large, decentralized vulnerability that current regulations barely touch.

Analysis supported by the Department of Energy has shown that these devices are often insecure. By compromising a relatively small percentage of these inverters, my colleagues and I found that an attacker could manipulate their power output to cause severe instabilities across the distribution network. Unlike centralized power plants protected by guards and security systems, these devices sit in private homes and businesses.

Accounting for the Physical

Defending American infrastructure requires moving beyond the compliance checklists that currently dominate the industry. Defense strategies now require a level of sophistication that matches the attacks. This implies a fundamental shift toward security measures that take into account how attackers could manipulate physical machinery.

The integration of internet-connected computers into power grids, factories and transportation networks is creating a world where the line between code and physical destruction is irrevocably blurred.

Ensuring the resilience of critical infrastructure requires accepting this new reality and building defenses that verify every component, rather than unquestioningly trusting the software and hardware – or the green lights on a control panel.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.