Some major oil companies such as Shell and BP that once were touted as leading the way in clean energy investments are now pulling back from those projects to refocus on oil and gas production. Others, such as Exxon Mobil and Chevron, have concentrated on oil and gas but announced recent investments in carbon capture projects, as well as in lithium and graphite production for electric vehicle batteries.

National oil companies have also been investing in renewable energy. For example, Saudi Aramco has invested in clean energy while at the same time asserting that it’s unrealistic to phase out oil and gas entirely.

But the larger question is why oil companies would invest in clean energy at all, especially at a time when many federal clean energy incentives are being eliminated and climate science is being dismantled, at least in the United States.

Some answers depend on whom you ask. More traditional petroleum industry followers would urge the companies to keep focused on their core fossil fuel businesses to meet growing energy demand and corresponding near-term shareholder returns. Other shareholders and stakeholders concerned about sustainability and the climate – including an increasing number of companies with sustainability goals – would likely point out the business opportunities for clean energy to meet global needs.

Other answers depend on the particular company itself. Very small producers have different business plans than very large private and public companies. Geography and regional policies can also play a key role. And government-owned companies such as Saudi Aramco, Gazprom and the China National Petroleum Corp. control the majority of the world’s oil and gas resources with revenues that support their national economies.

Despite the relatively modest scale of investment in clean energy by oil and gas companies so far, there are several business reasons oil companies would increase their investments in clean energy over time.

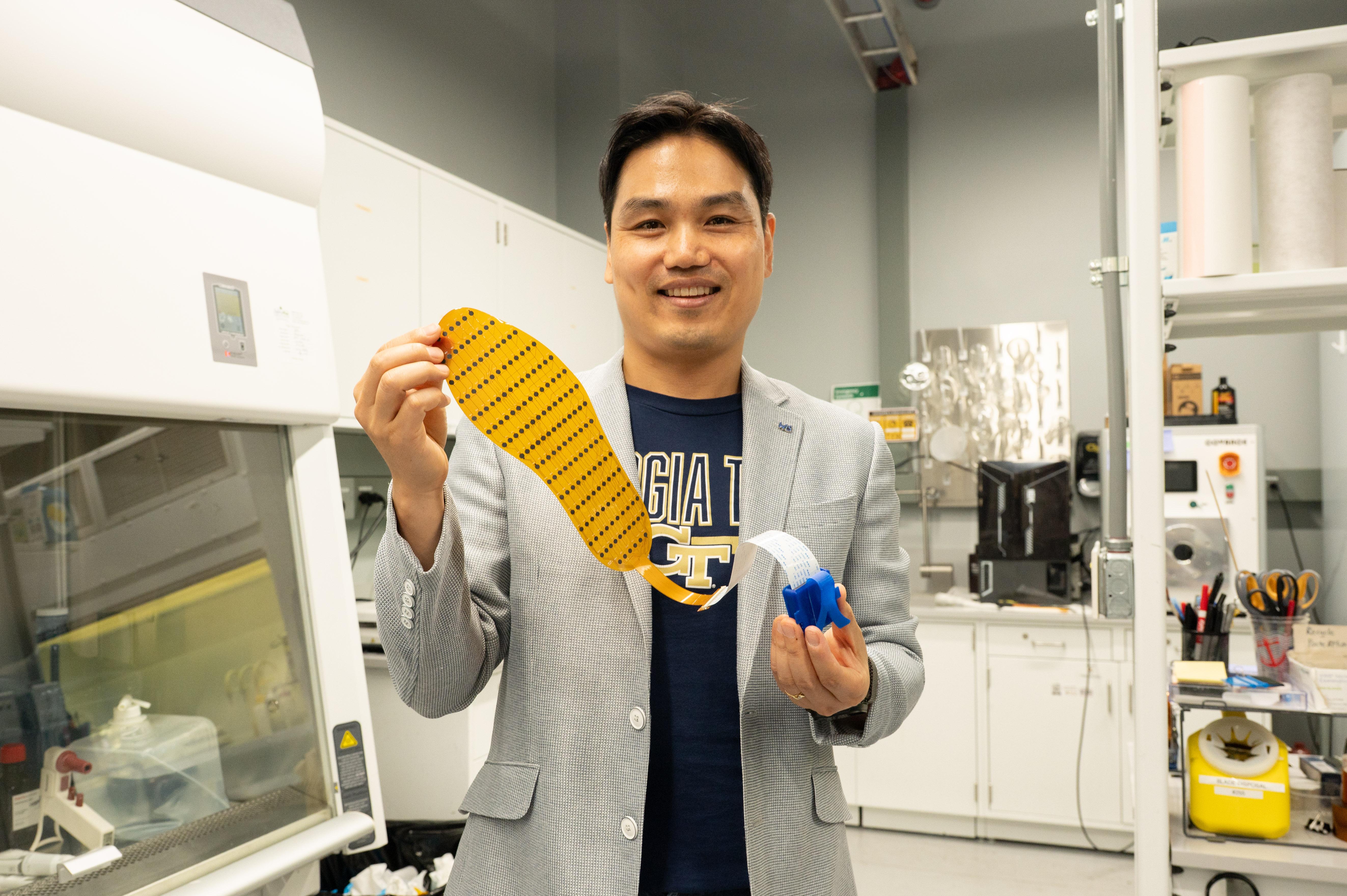

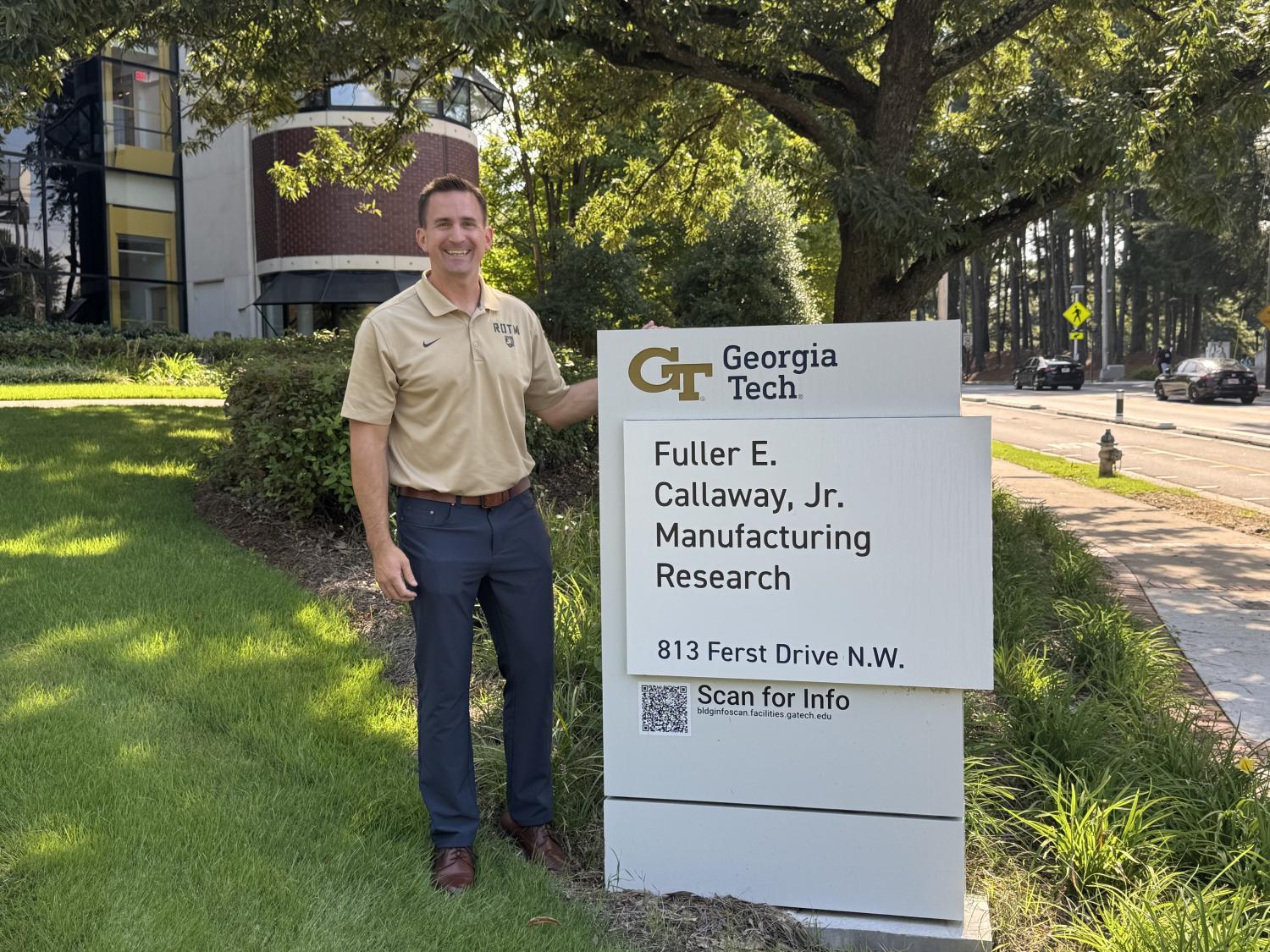

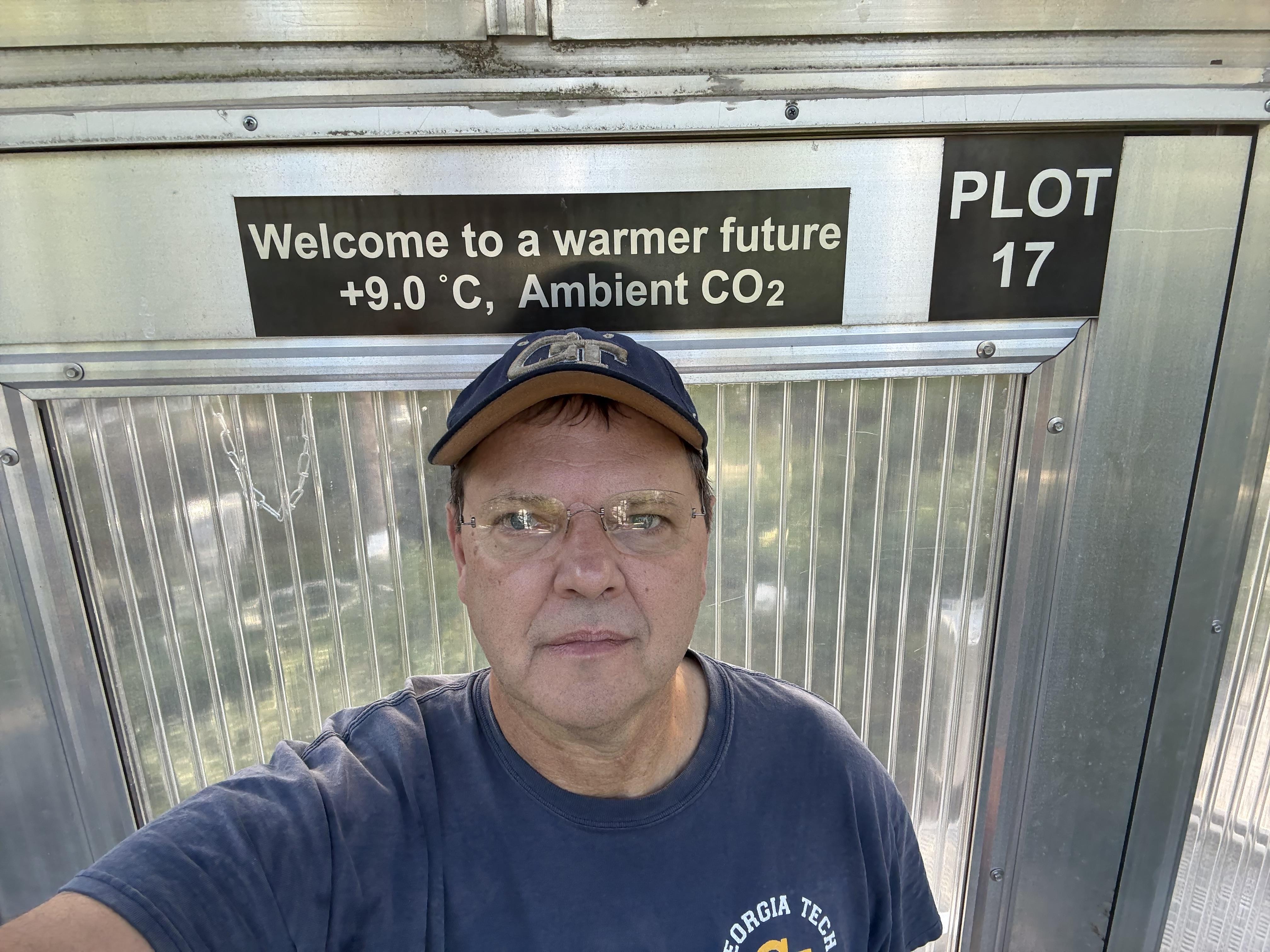

The oil and gas industry has provided energy that has helped create much of modern society and technology, though those advances have also come with significant environmental and social costs. My own experience in the oil industry gave me insight into how at least some of these companies try to reconcile this tension and to make strategic portfolio decisions regarding what “green” technologies to invest in. Now the managing director and a professor of the practice at the Ray C. Anderson Center for Sustainable Business at Georgia Tech, I seek ways to eliminate the boundaries and identify mutually reinforcing innovations among business interests and environmental concerns.

Diversification and Financial Drivers

Just like financial advisers tell you to diversify your 401(k) investments, companies do so to weather different kinds of volatility, from commodity prices to political instability. Oil and gas markets are notoriously cyclical, so investments in clean energy can hedge against these shifts for companies and investors alike.

Clean energy can also provide opportunities for new revenue. Many customers want to buy clean energy, and oil companies want to be positioned to cash in as this transition occurs. By developing employees’ expertise and investing in emerging technologies, they can be ready for commercial opportunities in biofuels, renewable natural gas, hydrogen and other pathways that may overlap with their existing, core business competencies.

Fossil fuel companies have also found what other companies have: Clean energy can reduce costs. Some oil companies not only invest in energy efficiency for their buildings but use solar or wind to power their wells. And adding renewable energy to their activities can also lower the cost of investing in these companies.

Public Pressure

All companies, including those in oil and gas, are under growing pressure to address climate change, from the public, from other companies with whom they do business and from government regulators – at least outside the U.S. For example, campaigns seeking to reduce investment in fossil fuels are increasing along with climate-related lawsuits. Government policies focused on both mitigating carbon emissions and enhancing energy independence are also making headway in some locations.

In response, many oil companies are reducing their own operational emissions and setting targets to offset or eliminate emissions from products that they sell – though many observers question the viability of these commitments. Other companies are investing in emerging technologies such as hydrogen and methods to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

Some companies, such as BP and Equinor, have previously even gone so far as rebranding themselves and acquiring clean energy businesses. But those efforts have also been criticized as “greenwashing,” taking actions for public relations value rather than real results.

How Far Can This Go?

It is even possible for a fossil fuel company to reinvent itself as a clean energy operation. Denmark’s Orsted – formerly known as Danish Oil and Natural Gas – transitioned from fossil fuels to become a global leader in offshore wind. The company, whose majority owner is the Danish government, made the shift, however, with the help of significant public and political support.

But most large oil companies aren’t likely to completely reinvent themselves anytime soon. Making that change requires leadership, investor pressure, customer demand and shifts in government policy, such as putting a price or tax on carbon emissions.

To show students in my sustainability classes how companies’ choices affect both the environment and the industry as a whole, I use the MIT Fishbanks simulation. Students run fictional fishing companies competing for profit. Even when they know the fish population is finite, they overfish, leading to the collapse of the fishery and its businesses. Short-term profits cause long-term disaster for the fishery and the businesses that depend on it.

The metaphor for oil and gas is clear: As fossil fuels continue to be extracted and burned, they release planet-warming emissions, harming the planet as a whole. They also pose substantial business risks to the oil and gas industry itself.

Yet students in a recent class showed me that a more collective way of thinking may be possible. Teams voluntarily reduced their fishing levels to preserve long-term business and environmental sustainability, and they even cooperated with their competitors. They did so without in-game regulatory threats, shareholder or customer complaints, or lawsuits.

Their shared understanding that the future of their own fishing companies was at stake makes me hopeful that this type of leadership may take hold in real companies and the energy system as a whole. But the question remains about how fast that change can happen, amid the accelerating global demand for more energy along with the increasing urgency and severity of climate change and its effects.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.