2026 Southeast Regional Clinical and Translational Science Conference

Conference Website

Join us at Callaway Resort and Gardens as we bring together researchers from across the region to present the best new health-related preclinical, clinical, implementation, and population-based research and build collaborative relationships. Hosted by the Georgia CTSA, with participation from:

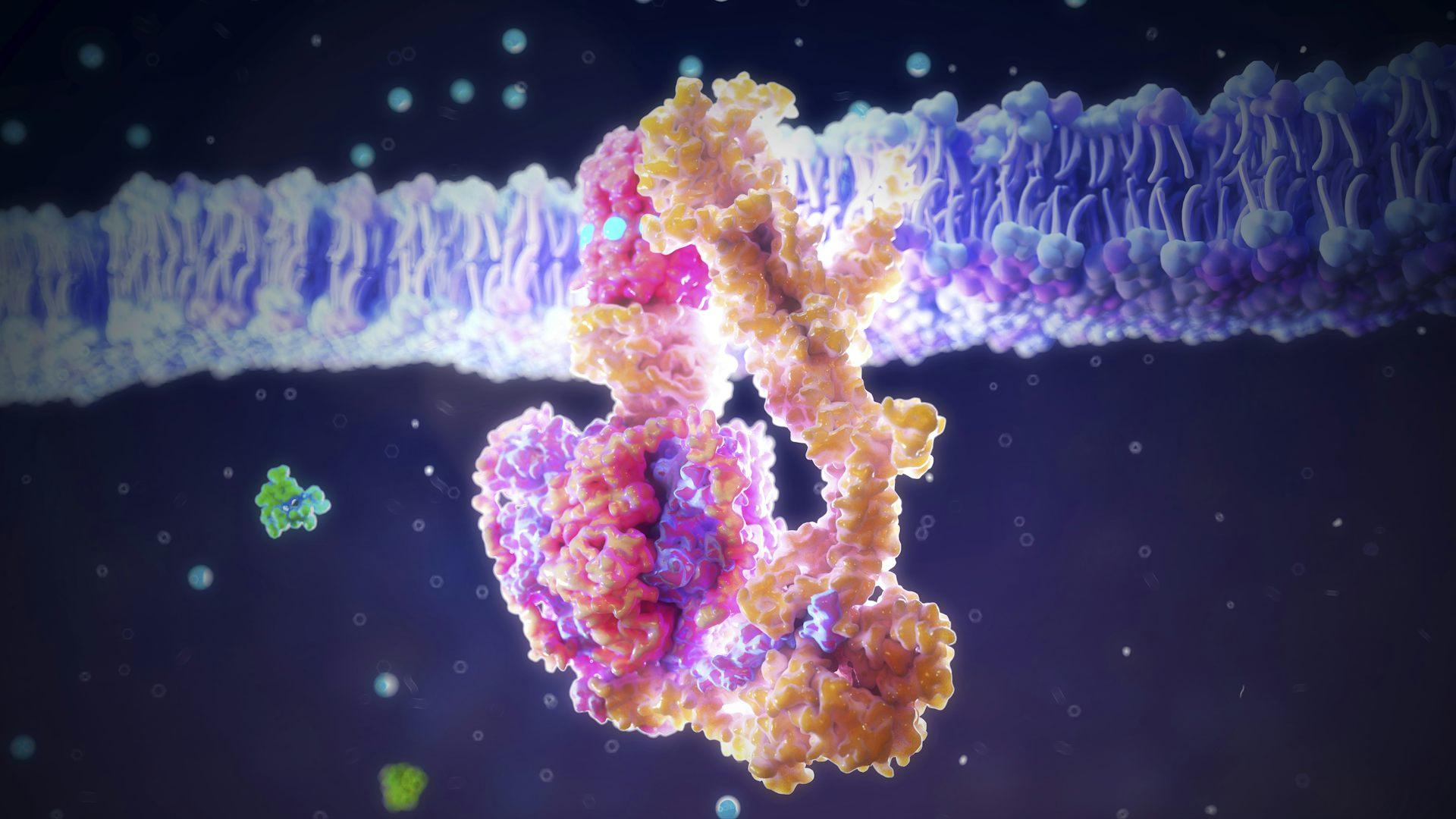

Breathtaking Breakthrough: Lung-on-a-Chip Defends Itself

Sep 24, 2025 —

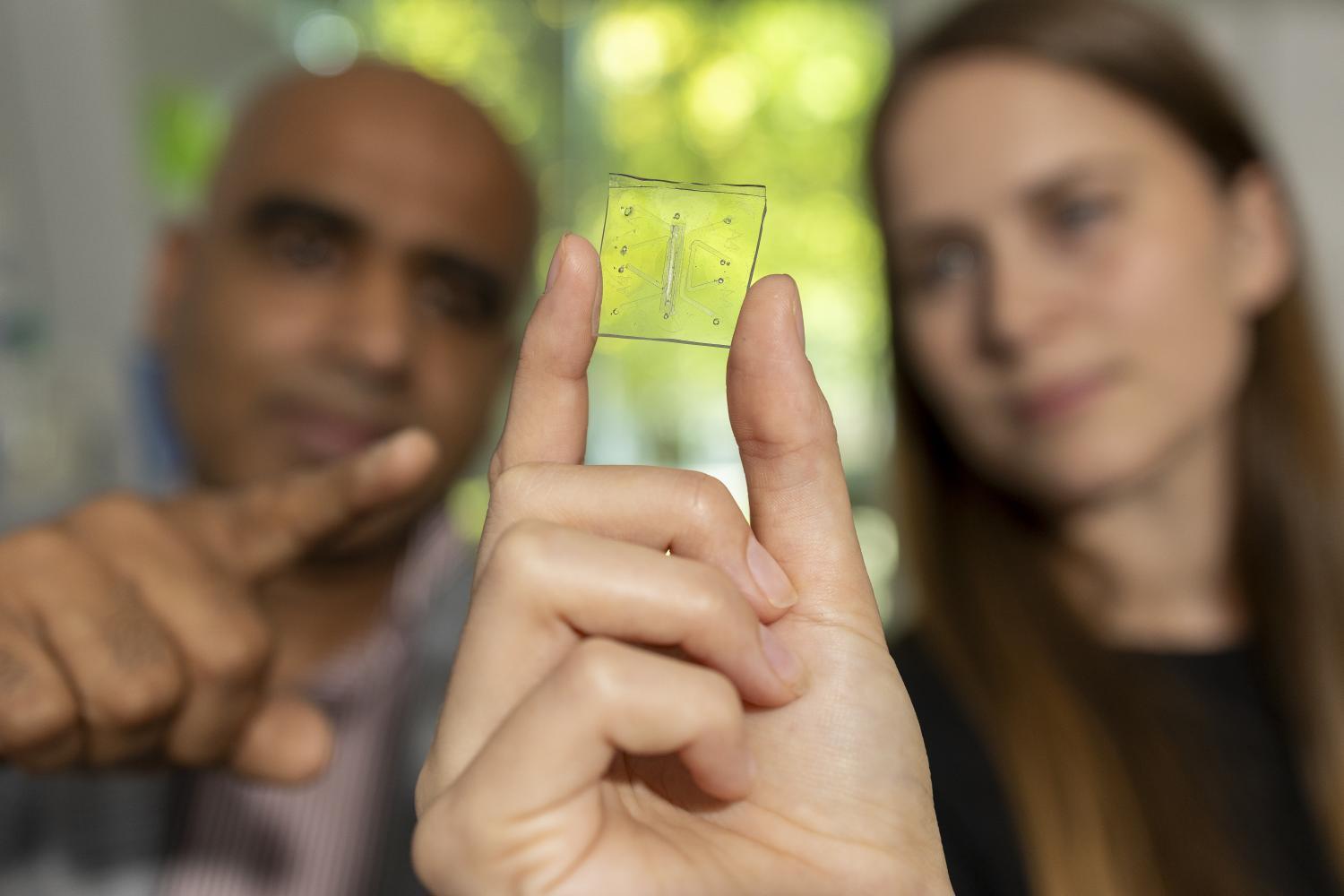

Ankur Singh and Rachel Ringquist point to the microscopic lung-on-a-chip that has a built-in immune system.

On a clear polymer chip, soft and pliable like a gummy bear, a microscopic lung comes alive — expanding, circulating, and, for the first time, protecting itself like a living organ.

For Ankur Singh, director of Georgia Tech’s Center for Immunoengineering, watching immune cells rush through the chip took his breath away. Singh co-directed the study with longtime collaborator Krishnendu “Krish” Roy, former Regents Professor and director of the NSF Center for Cell Manufacturing Technologies at Tech and now the Bruce and Bridgitt Evans dean of engineering and University Distinguished Professor at Vanderbilt University. Rachel Ringquist, Roy’s graduate student, and now a postdoctoral fellow with Singh, led the work as part of her doctoral dissertation.

“That was the ‘wow’ moment,” Singh said. “It was the first time we felt we had something close to a real human lung.”

Lung-on-a-chip platforms provide researchers a window into organ behavior. They are about the size of a postage stamp, etched with tiny channels and lined with living human cells. Roy and Singh’s innovation was adding a working immune system — the missing piece that turns a chip into a true model of how the lung fights disease.

Now, researchers can watch how lungs respond to threats, how inflammation spreads, and how healing begins.

The Human Stakes

For millions of people struggling with lung disease, everyday life can feel nearly impossible, whether it’s climbing stairs, carrying groceries, or even laughing too hard. Doctors and scientists have attempted for decades to unlock what really happens inside fragile lungs.

"This unique lung-on-a-chip model opens new, preclinical pathways of discovery that will allow researchers to better understand the interplay of immune responses to severe viral infections and evaluate critical antiviral treatments,” said Roy.

For Singh, the Carl Ring Family Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering with a joint appointment in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, this research is deeply personal. He lost an uncle when an infection overwhelmed his cancer-weakened immune system.

“That experience stays with you,” Singh reflected. “It made me want to build systems that could predict and prevent outcomes like that, so fewer families go through what mine did. I think about my uncle all the time. If work like this means fewer families lose someone they love, then it’s worth everything.”

That motivation pushed his team to reimagine what a lung-on-a-chip could do, setting the stage for the breakthroughs that followed.

When the Lung Fought Back

The turning point came when Roy’s and Singh’s team peered through a microscope and saw something no one had ever witnessed on a chip: blood and immune cells coursing through tiny vessel-like structures, behaving just as they do in a living lung.

For years, researchers had struggled to add immunity to organ-on-a-chip systems. Immune cells often died quickly or failed to circulate and interact with tissue the way they do in people. the team solved that problem, creating a chip where immune cells could survive and coordinate a defense.

“It was an amazing breakthrough moment,” Singh said.

The true test came when the team introduced a severe influenza virus infection. The lung mounted an immune response that closely mirrored what doctors see in patients. Immune cells rushed to the site of infection, inflammation spread through tissue, and defenses activated in response.

“That was when we realized this wasn’t just a model,” Singh said. “It was capturing the real biology of disease.”

Singh and Roy’s research is published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

A More Human Approach

For decades, lung research has relied on animal models. But mice don’t get asthma like children. Their bodies don’t mount the same defenses.

“Five mice in a cage may respond the same way, but five humans won’t,” Singh explained. “Our chip can reflect that difference. That’s what makes it more accurate, and why it could dramatically reduce the need for animal models.”

Krish Roy emphasized its potential.

“The Food and Drug Administration’s strategic vision on reducing animal testing and developing predictive non-animal models aligns perfectly with our work. This device goes further than ever before in modeling human severe influenza and providing unprecedented insights into the complex lung immune response,” he said.

Fighting More Than the Flu

What began with influenza now expands to a wider range of diseases. Roy and Singh believes the platform can be used to study asthma, cystic fibrosis, lung cancer, and tuberculosis. The researchers are also working to integrate immune organs, showing how the lung coordinates with the body’s defenses.

The long-term vision is personalized medicine: chips built from a patient’s own cells to predict which therapy will work best. Scaling, clinical validation, and regulatory approval will take years, but Singh is undeterred.

“Imagine knowing which treatment will help you before you ever take it,” Singh said. “That’s where we’re headed.”

Where we’re headed, the future doesn’t wait for illness. Instead, it anticipates it, intercepts it, and rewrites the outcome.

Georgia Tech postdoctoral researcher Rachel Ringquist was the first author leading the study.

This research was supported by Wellcome Leap, with additional funding from the National Institutes of Health, Carl Ring Family Endowment, and the Marcus Foundation.

Ringquist, R., Bhatia, E., Chatterjee, P. et al. An immune-competent lung-on-a-chip for modelling the human severe influenza infection response. Nature Biomedical Engineering, September 2025 Vol.9 No.9

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01491-9

Michelle Azriel Sr. Writer-Editor

Immunoengineering Trainee Seminar

Refreshments for In-person attendees.

**Click HERE to register for Zoom link

Featured Speakers

"Graph-based 2D and 3D Spatial Gene Neighborhood Networks of Single Cells in Gels and Tissues” - Zhou Fang, Ph.D. Student, Coskun Lab

Georgia CTSA - K-Club

REGISTER HERE for Zoom link

A facilitated panel discussion, led by Beth Stenger, MD, to discuss ways to foster partnerships outside of academia.

Panelists:

A Step Forward: New Smart Shoe Insert Could Improve Mobility for People With Walking Problems

Sep 18, 2025 —

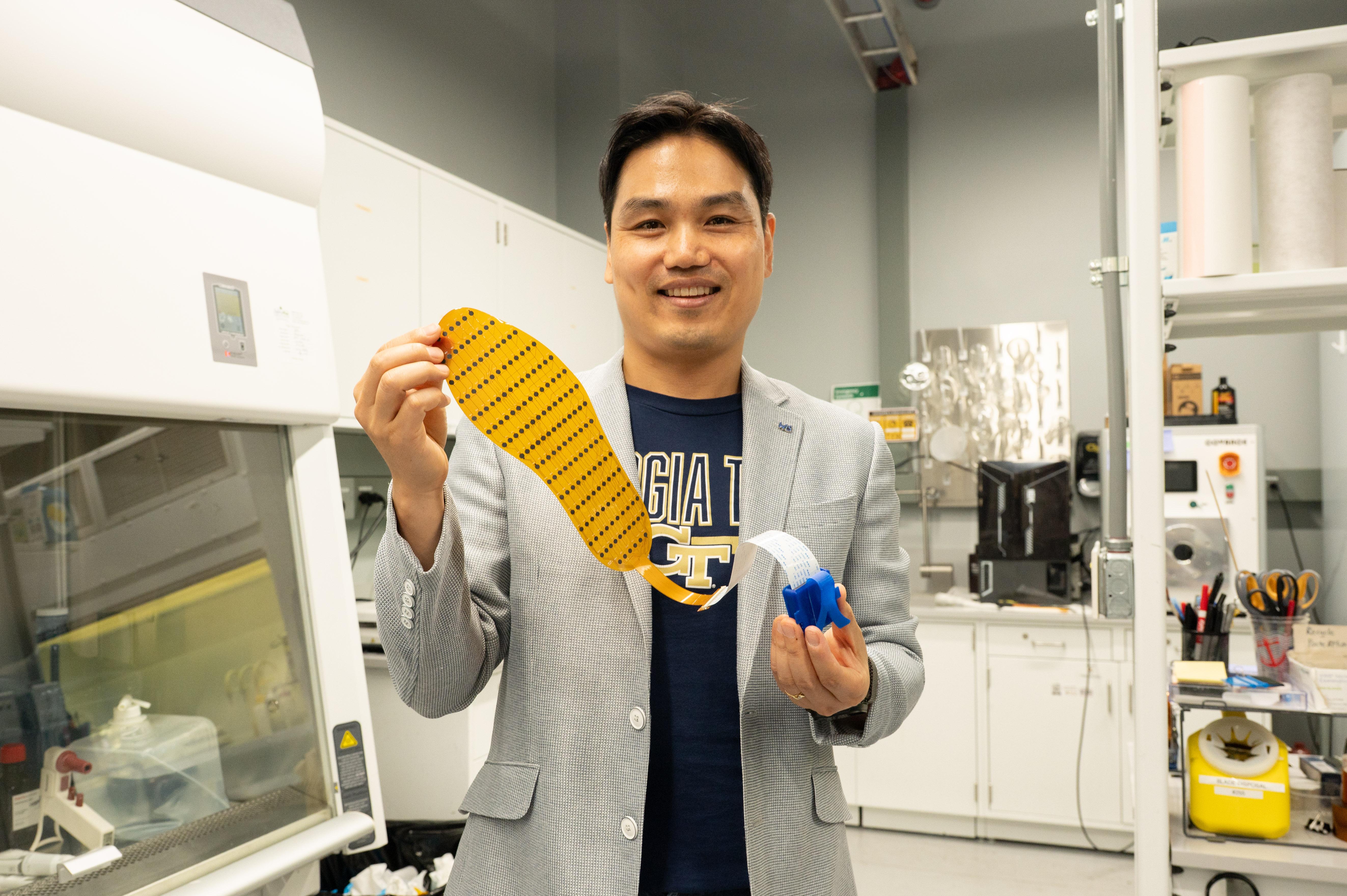

Hong Yeo holds the wearable electronic device made of more than 170 thin, flexible sensors that measure foot pressure — a key metric for determining whether someone is off-balance. [Photos by Joya Chapman]

Maintaining balance while walking may seem automatic — until suddenly it isn’t. Gait impairment, or difficulty with walking, is a major liability for stroke and Parkinson’s patients. Not only do gait issues slow a person down, but they are also one of the top causes of falls. And solutions are often limited to time-intensive and costly physical therapy.

A new wearable electronic device that can be inserted inside any shoe may be able to address this challenge. The device, developed by Georgia Tech researchers, is made of more than 170 thin, flexible sensors that measure foot pressure — a key metric for determining whether someone is off-balance. The sensor collects pressure data, which the researchers could eventually use to predict which changes lead to falls.

The researchers presented their work in the paper, “Flexible Smart Insole and Plantar Pressure Monitoring Using Screen-Printed Nanomaterials and Piezoresistive Sensors.” It was the cover paper in the August edition of ACSApplied Materials & Interfaces.

Pressure Points

Smart footwear isn’t new — but making it both functional and affordable has been nearly impossible. W. Hong Yeo’s lab has made its reputation on creating malleable medical devices. The researchers rely on the common commercial practice of screen-printing electronics to screen-print sensors. They realized they could apply this printing technique to address walking difficulties.

“Screen-printing is advantageous for developing medical devices because it's low-cost and scalable,” said Yeo, the Peterson Professor and Harris Saunders Jr. Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering. “So, when it comes to thinking about commercialization and mass production, screen-printing is a really good platform because it's already been used in the electronics industry.”

Making the device accessible to the everyday user was paramount for Yeo’s team. A key innovation was making sure the wearable is thin enough to be comfortable for the wearer and easy to integrate with other assistive technologies. The device uses Bluetooth, enabling a smartphone to collect data and offer the future possibility of integrating with existing health monitoring applications.

Possibilities for real-world adaptation are promising, thanks to these innovations. Lightweight and small, the wearable could be paired with robotics devices to help stroke and Parkinson’s patients and the elderly walk. The high number of sensors could make it easier for researchers to apply a machine learning algorithm that could predict falls. The device could even enable professional athletes to analyze their performance.

Regardless of how the device is used, Yeo intends to keep its cost under $100. So far, with funding from the National Science Foundation, the researchers have tested the device on healthy subjects. They hope to expand the study to people with gait impairments and, eventually, make the device commercially available.

“I'm trying to bridge the gap between the lack of available devices in hospitals or medical practices and the lab-scale devices,” Yeo said. “We want these devices to be ready now — not in 10 years.”

With its low-cost, wireless design and potential for real-time feedback, this smart insole could transform how we monitor and manage walking difficulties — not just in clinical settings, but in everyday life.

Tess Malone, Senior Research Writer/Editor

tess.malone@gatech.edu

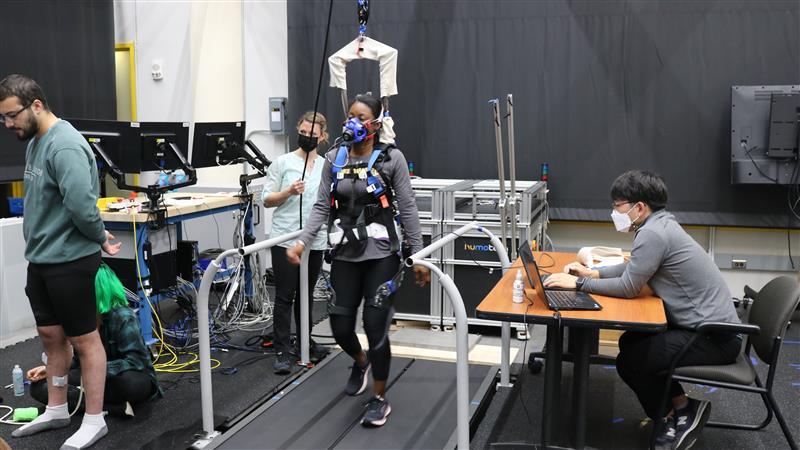

The Robotic Breakthrough That Could Help Stroke Survivors Reclaim Their Stride

Sep 18, 2025 — Atlanta

Georgia Tech's AI-fueled exoskeleton adapts to every step, helping patients relearn to walk with less effort and more confidence.

Crossing a room shouldn’t feel like a marathon. But for many stroke survivors, even the smallest number of steps carries enormous weight. Each movement becomes a reminder of lost coordination, muscle weakness, and physical vulnerability.

A team of Georgia Tech researchers wanted to ease that struggle, and robotic exoskeletons offered a promising path. Their findings point to a simple but powerful shift: exoskeletons that adapt to people, rather than forcing people to adapt to the machine. Using artificial intelligence (AI) to learn the rhythm of patients’ strides in real time, the team showed how these devices can reduce strain and increase efficiency. They also demonstrated how the technology can help restore confidence for stroke survivors.

The Robot Finds the Rhythm

A robotic exoskeleton is a wearable device that helps people move with mechanical support. Traditional exoskeletons require endless manual adjustments — turning knobs, calibrating settings, and tweaking controls.

“It can be frustrating, even nearly impossible, to get it right for each person,” said Aaron Young, associate professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering. “With AI, the exoskeleton figures out the mapping itself. It learns the timing of someone’s gait through a neural network, without an engineer needing to hand-tune everything.”

The software monitors each step, instantly updates, and fine-tunes the support it provides. Over time, the exoskeleton aligns its movements with the unique gait of the person wearing it. In this study, the research team used a hip exoskeleton, which provides torque at the hip joint — in other words, adding power to help stroke survivors walk or move their legs more easily.

Taking Smarter Steps

Walking after a stroke can be tough and unpredictable. A patient’s stride can change from one day to the next, and even from one step to the next. Most exoskeletons aren’t built for that kind of variation. They are designed around the steady, even gait of healthy young adults, which can leave stroke survivors feeling more unsteady than supported.

Young’s breakthrough, detailed in IEEE Transactions on Robotics, is a neural network — a type of AI that learns patterns much like the human brain does. Sensors at the hip pick up how someone is moving, and the network translates those signals into just the right boost of power to support each step. It quickly figures out a person’s unique walking pattern. But lead clinician Kinsey Herrin said the AI’s learning doesn’t stop there. It keeps adjusting as the patient walks, so the exoskeleton can stay in sync even during stride shifts.

“The speed really surprised us,” Young said. “In just one to two minutes of walking, the system had already learned a person’s gait pattern with high accuracy. That’s a big deal, to adapt that quickly and then keep adapting as they move.”

Tests showed the system was far more accurate than the standard exoskeleton. It reduced errors in tracking stroke patients’ walking patterns by 70%.

Young emphasized that this research is about more than metrics. “When you see someone able to walk farther without becoming exhausted, that’s when you realize this isn’t just about robotics — it’s about giving people back a measure of independence,” he said.

Adapting Anywhere

Every exoskeleton comes with its own set of sensors, so the data they collect can look completely different from one device to the next. A neural network trained on one machine often stumbles when it’s moved to another. To get around that, Young’s team designed software that works like a universal adapter plug — no matter what device it’s connected to, it converts the signals into a form the AI can use. After just 10 strides of calibration, the system cut error rates by more than 75%.

“The goal is that someone could strap on a device, and, within a minute, it feels like it was built just for them,” Young said.

A Step Toward the Future

While the study centered on stroke survivors, the implications are far broader. The same adaptive approach could support older adults coping with age-related muscle weakness, people with conditions like Parkinson’s or osteoarthritis, or even children with neurological disabilities.

Young and his team are now running clinical trials to measure how well the AI-powered exoskeleton supports people in a wide range of everyday activities.

“There’s no such thing as an ‘average’ user,” Young said. “The real challenge is designing technology that can adapt to the full spectrum of human mobility.”

If Georgia Tech’s exoskeleton can rise to that challenge, the promise goes well beyond the lab. It could mean a world where technology doesn’t just help people walk — it learns to walk with them.

Inseung Kang, who holds a B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. from Georgia Tech, is the paper’s lead author and now an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. He explained that the real promise is in what comes next.

“We’ve developed a system that can adjust to a person’s walking style in just minutes. But the potential is even greater. Imagine an exoskeleton that keeps learning with you over your lifetime, adjusting as your body and mobility change. Think of it as a robot companion that understands how you walk and gives you the right assistance every step of the way.”

Aaron Young is affiliated with Georgia Tech’s Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Machines.

This research was primarily funded by a grant (DP2HD111709-01) from the National Institutes of Health New Innovator Award Program.

Michelle Azriel

Senior Writer – Editor

Institute Communications

mazriel3@gatech.edu

Molecular ‘Fossils’ Offer Microscopic Clues to the Origins of Life – But They Take Care to Interpret

Sep 16, 2025 —

ATP synthase is an enzyme that has been using phosphate to generate life’s energy for millions of years. Nanoclustering/Science Photo Library via Getty Images

The questions of how humankind came to be, and whether we are alone in the universe, have captured imaginations for millennia. But to answer these questions, scientists must first understand life itself and how it could have arisen.

In our work as evolutionary biochemists and protein historians, these core questions form the foundation of our research programs. To study life’s history billions of years ago, we often use clues called molecular “fossils” – ancient structures shared by all living organisms.

Recently, we discovered that an important molecular fossil found in an ancient protein family may not be what it seems. The dilemma centers, in part, on a simple question: What does it mean if a simple molecular structure – the fossil – is found in every single organism on Earth? Do molecular fossils point to the seeds that gave rise to modern biological complexity, or are they simply the stubborn pieces that have resisted erosion over time? The answers have far-reaching implications for how scientists understand the origins of biology.

Follow the Phosphorus to Follow Life

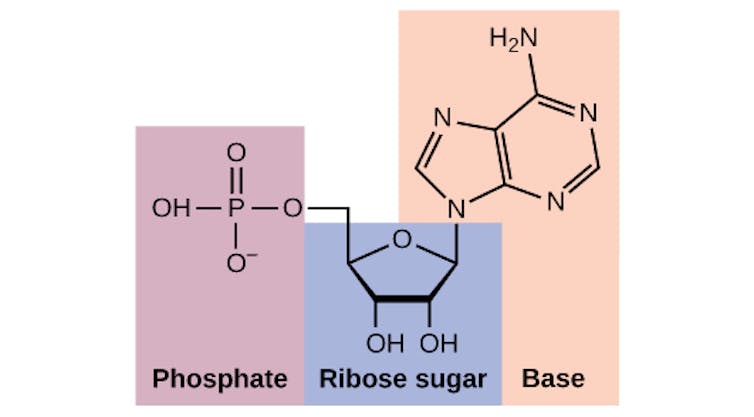

Life is made of many different building blocks, one of the most important of which is the chemical element phosphorus. Phosphorus makes up part of your genetic material, powers complex metabolic reactions and acts as a molecular switch to control enzymes.

Phosphorus compounds – specifically a charged form called phosphate – have a number of unique chemical properties that other biological compounds cannot match. In the words of the pioneering organic chemist F.H. Westheimer, they are chemically able to “do almost everything.”

Their unique combination of stability, versatility and adaptability is why many researchers argue that following phosphorus is key to finding life. The presence of phosphorus both close to home – in the ocean or on one of Saturn’s moons – and in the farthest reaches of our galaxy is strong evidence for the potential for life beyond Earth.

Phosphate is part of many essential biological molecules, including the building blocks of DNA. Charles Molnar and Jane Gair, CC BY-SA

If phosphorus is so critical to life, how did early biology predating cells first use it?

Today, biological organisms are able to make use of phosphates through proteins – molecular machines that regulate all aspects of life. By binding to proteins, phosphates regulate metabolism and cellular communication, and they serve as a source of cellular energy.

Further, the process of phosphorylation, or adding a phosphate group to a protein, is ubiquitous in biology and allows proteins to perform functions their individual building blocks cannot. Without proteins, the existence of organisms such as bacteria and humans may not be possible.

Given how essential phosphorus is to life, scientists hypothesize that phosphate binding was among the first biological functions to emerge on Earth. In fact, current evidence suggests that the first phosphate-binding proteins are truly ancient – even older than the last universal common ancestor, the hypothetical mother cell to all life on Earth that existed around 4 billion years ago.

A Mysterious Phosphate-Binding Fossil

One family of phosphate-binding proteins, called P-loop NTPases, regulates everything from the communication between cells to the storage of energy and are found across the tree of life. Because P-loop NTPases are among the most ancient protein families, analyzing their properties can provide key insights into both the emergence of proteins and how primitive life used phosphates.

Although P-loop NTPases are diverse in structure, they share a common motif called a P-loop. This component binds to phosphate by wrapping a nest of amino acids – the building blocks that make up proteins – around the molecule. Every known organism has multiple families of P-loop NTPase, which makes the P-loop an excellent example of a molecular fossil that can provide clues about the evolution of life. Our crude analysis of the human genome estimates that humans have about 5,000 copies of P-loops.

When part of a larger protein structure, the P-loop folds like origami into a shape that is ideal for hugging a phosphate molecule. These nests are extremely similar to each other, even when the surrounding proteins are only distantly related in function. A landmark study in 2012 argued that even if the P-loop nest is extracted from a protein, it can still bind to phosphate. In other words, the ability of a P-loop to form a nest is determined by its interactions with phosphate, not its protein scaffold.

This study provided the first evidence that some forms of the P-loop sequence could have functioned billions of years ago, even before the emergence of large, complex proteins. If true, this implies that P-loop nests may have seeded the emergence and evolution of many of the phosphate-binding proteins seen today.

Interrogating the History of the P-loop

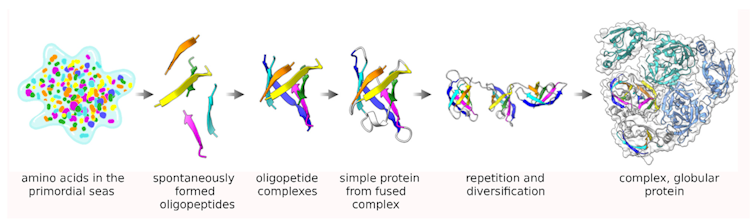

The pioneer of bioinformatics, Margaret Oakley Dayhoff, hypothesized in 1966 that the large collection of big proteins seen today arose from small peptides that were duplicated and fused over long periods of time. Although P-loops may have evolved in a different way, Dayhoff’s realization was the first to clarify how complex forms could have arisen from much simpler ones.

Inspired by Dayhoff’s hypothesis, we sought to interrogate the role that simple P-loops may have played in the evolution of the complex proteins key to life. Our findings challenge what’s currently known about these molecular fossils.

The Dayhoff hypothesis proposed that large, complex proteins arose from the duplication and merging of smaller, simpler peptides over time. Merski et al./Biomolecules, CC BY-SA

Using computer models, we compared a range of P-loops from the P-loop NTPase family to a control group made of the same amino acids but in a different order. While these control loops are also found in proteins, they do not form nests.

Although the P-loops and the control loops are very different in their nest-forming ability, we found that they both are able to form transient nests when embedded in proteins. This meant that, contrary to popular belief, the amino acid sequence of P-loops aren’t special in their ability to form nests – as would be expected if they alone were the seeds for many modern proteins.

A Fossil Eroded Over Time

Our work strongly suggests that while the P-loop is a molecular fossil, the true nature of its form billions of years ago may have been eroded by the sands of time.

For example, when we repeated our simulations in a different solvent – specifically methanol – we found that P-loops situated in their parent proteins were able to regain some of their ability to form nests. This doesn’t mean that being in methanol drove the first proteins with P-loops to form the nests critical for life. But it does emphasize the importance of considering the surrounding environment when studying peptides and proteins.

Just as archaeologists know to be careful in how they interpret physical fossils, historians of protein evolution could take similar care in their interpretation of molecular fossils. Our results complicate the current understanding of early protein evolution and, consequently, some aspects of the origins of life.

In resetting the field’s broader understanding of how these crucial proteins emerged, scientists are poised to start rewriting our own evolutionary history on this planet.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Authors:

Caroline Lynn Kamerlin, professor of chemistry and biochemistry, Georgia Institute of Technology

Liam Longo, specially appointed associate professor, Earth-Life Science Institute, Institute of Science Tokyo

Media Contact:

Shelley Wunder-Smith

shelley.wunder-smith@research.gatech.edu

IBB Core Facilities Educational Seminar

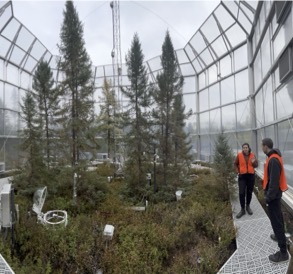

Meet the Microbes: What a Warming Wetland Reveals About Earth’s Carbon Future

Sep 16, 2025 —

An arial photo of the SPRUCE experiment.

Between a third and half of all soil carbon on Earth is stored in peatlands, says Tom and Marie Patton Distinguished Professor Joel Kostka. These wetlands — formed from layers and layers of decaying plant matter — span from the Arctic to the tropics, supporting biodiversity and regulating global climate.

“Peatlands are essential carbon stores, but as temperatures warm, this carbon is in danger of being released as carbon dioxide and methane,” says Kostka, who is also the associate chair for Research in the School of Biological Sciences and the director of Georgia Tech for Georgia’s Tomorrow. Understanding the ratio of carbon dioxide to methane is critical, he adds, because while both are greenhouse gasses, methane is significantly more potent.

Kostka is the corresponding author of a new study unearthing how and why peatlands are producing carbon dioxide and methane.

The research, “Northern peatland microbial communities exhibit resistance to warming and acquire electron acceptors from soil organic matter,” was published this summer in Nature Communications, and was led by co-first authors Borja Aldeguer-Riquelme, a postdoctoral research associate in the Environmental Microbial Genomics Laboratory, and Katherine Duchesneau, a Ph.D. student in the School of Biological Sciences.

The study builds on a decade of research at the Oak Ridge National Lab’s Spruce and Peatland Responses Under Changing Environments (SPRUCE) experiment, a long-term research project in Minnesota that allows researchers to warm whole sections of wetland from tree top to bog bottom.

“Over the past 10 years, we’ve shown that warming in this large-scale climate experiment increases greenhouse gas production,” Kostka says. “But while warming makes the bog produce more methane, we still observe a lot more CO2 production than methane. In this paper, we take a critical step towards discovering why — and describing the mechanisms that determine which gases are released and in what amounts.”

Methane mystery

The subdued methane production in peatlands has been a long-standing mystery. In water-saturated wetlands, oxygen is scarce, but microbes still need to respire — a type of ‘breathing’ that allows them to produce energy for metabolic function. Without oxygen, microbes use nitrate, sulfate, or metals to respire — still releasing carbon dioxide in the process. However, if these ingredients aren’t present, microbes ‘breathe’ in a way that releases methane.

Since nitrate, sulfate, and metals are relatively rare in peatlands, methane production should be the most likely pathway, but surprisingly, observations show the opposite. “In both fieldwork and lab experiments, peatlands produce much more carbon dioxide than methane,” Kostka explains. “It’s puzzling because the soil conditions should help methane production dominate.”

To solve this mystery, the team leveraged a suite of cutting-edge genetic tools called “omics” — metagenomics (studying DNA), metatranscriptomics (studying RNA), and metabolomics (a technique used to study the “leftovers” of metabolism), providing a detailed look under the hood of the microbial “engine” that cycles organic matter in wetlands. It also gave a new window into the diversity of soil microbes in wetlands: 80 percent of the organisms identified in the study were new at the genus level.

‘Omics’ innovations

Over the course of several years, the team collected samples from a peatland enclosed in an experimental chamber that was slowly warmed, then analyzed the samples using omics to see how they changed. Initially, they hypothesized that warming the soil would cause microbial communities to change quickly. “Microbes can evolve and grow rapidly,” Kostka says. “But that didn’t happen.”

The DNA-based methods showed that while the microbial communities stayed largely stable, the bog did release more greenhouse gasses as it warmed. To assess the metabolic potential of the microbes, Duchesneau and Aldeguer-Riquelme constructed microbial genomes, investigating how they were decomposing the organic matter in peatlands and cycling carbon.

“We found that microbial activity increases with warming, but the growth response of microbial communities lags behind these changes in physiological or metabolic activity,” Kostka says. He cautions that this doesn’t necessarily mean that wetland communities won’t change as climates warm — just that these shifts might come behind metabolic ones.

A diversity of discoveries

And the methane? The team believes that microbes may be breaking down organic matter to access the key ingredients for producing carbon dioxide — nitrate, sulfate, and metals — though more research is currently underway to investigate this.

“Doing this type of integrated omics research in soil systems is still incredibly difficult,” Kostka says. The challenge is multifaceted: the research leverages years of experiments, long-term datasets, advanced laboratory techniques, and fieldwork innovations.

At SPRUCE, experimental chambers are about 1,000 square feet. While it’s an impressive experimental setup, researchers still must be careful: “We need to take soil samples for many years, so if we take too many, there’d be no soil left!” Kostka explains. “Part of our research involves developing better, non-destructive sampling techniques.”

The other challenge lies in what makes these peatlands so unique: it’s very hard to detect small changes because of the sheer diversity of organisms present. “Every time we conduct this type of research, we learn more about these incredible systems,” he says. “There’s always something new.”

Postdoctoral Researchers Caitlin Petro and Borja Aldeguer-Riquelme inside a SPRUCE chamber in 2023.

Ph.D. student Katherine Duchesneau sampling porewater inside an experimental SPRUCE chamber.

Postdoctoral Researcher Caitlin Petro, PhD student Katherine Duchesneau, and undergraduate student Sekou Noble-Kuchera in a SPRUCE chamber.

Written by Selena Langner

Saad Bhamla Named 2025 Schmidt Polymath

Sep 16, 2025 —

Saad Bhamla, associate professor in Georgia Tech's School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

Saad Bhamla of Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (ChBE) is a member of a global cohort of eight scientists and engineers who were named Schmidt Polymaths. They will each receive up to $2.5 million over five years to pursue research in new disciplines or using new methodologies, Schmidt Sciences announced today.

As Schmidt Polymaths, the researchers pursue new approaches compared to previous work. The new cohort of polymaths will answer questions like how to expand access to healthcare with low-cost technologies, what happens to our chromosomes when we age and how to create more accurate computer simulations of climate.

Bhamla, associate professor in ChBE@GT, will develop low-cost technologies to tackle planetary-scale challenges, including AI-enabled point-of-care diagnostics in low-resource environments. He will also engineer autonomous morphing machines that adapt, evolve and learn like living systems.

The eight selected scientists represent the fifth cohort of the highly selective Schmidt Polymaths program. Awardees must have been tenured—or achieved similar status—within the previous three years. Previous cohorts have used the award to design new sensor devices, perform experiments at atomic resolutions, analyze trees of life with faster and more efficient algorithms, discover new mathematical formulas assisted by AI, and more.

Drawn from universities worldwide and selected through a competitive application process, Schmidt Polymaths are required to demonstrate past ability and future potential to pursue early-stage, novel research that would otherwise be challenging to fund—even without the current dramatic declines in U.S. funding for science.

“Our world is one deeply interconnected system---but to study it more deeply, we’ve divided it into increasingly narrow categories,” said Wendy Schmidt, who co-founded Schmidt Sciences with her husband Eric. “Schmidt Polymaths see the bigger picture, pursue answers beyond boundaries and expand the edges of what’s possible. Their work can help steer us all toward a healthier future, for people and the planet.”

About Schmidt Sciences

Schmidt Sciences is a nonprofit organization founded in 2024 by Eric and Wendy Schmidt that works to accelerate scientific knowledge and breakthroughs with the most promising, advanced tools to support a thriving planet. The organization prioritizes research in areas poised for impact including AI and advanced computing, astrophysics, biosciences, climate, and space—as well as supporting researchers in a variety of disciplines through its science systems program.

RELATED: Forbes featured Bhamla in the article: Saad Bhamla Is A Polymath

Brad Dixon, braddixon@gatech.edu