Pascal Van Hentenryck to Lead Georgia Tech’s AI Hub

May 01, 2024 —

Georgia Tech’s AI Hub will be directed by Pascal Van Hentenryck, announced Chaouki Abdallah, executive vice president for Research. Van Hentenryck, A. Russell Chandler III Chair and professor in the H. Milton Stewart School of Industrial and Systems Engineering, also directs the NSF Artificial Intelligence Institute for Advances in Optimization (AI4OPT).

Georgia Tech has been actively engaged in artificial intelligence (AI) research and education for decades. Formed in 2023, the AI Hub is a thriving network, bringing together over 1000 faculty and students who work on fundamental and applied AI-related research across the entire Institute.

“Pascal Van Hentenryck will drive innovation and excellence at the helm of Georgia Tech’s AI Hub,” said Abdallah. “His leadership of one of our three AI institutes has already shown his dedication to fostering impactful partnerships and cultivating a dynamic ecosystem for AI progress at Georgia Tech and beyond.”

The AI Hub aims to advance AI through discovery, interdisciplinary research, responsible deployment, and education to build the next generation of the AI workforce, as well as a sustainable future. Thanks to Tech’s applied, solutions-focused approach, the AI Hub is well-positioned to provide decision makers and stakeholders with access to world-class resources for commercializing and deploying AI.

“A fundamental question people are asking about AI now is, ‘Can we trust it?’” said Van Hentenryck. “As such, the AI Hub’s focus will be on developing trustworthy AI for social impact — in science, engineering, and education.”

U.S. News & World Report has ranked Georgia Tech among the five best universities with artificial intelligence programs. Van Hentenryck intends for the AI Hub to leverage the Institute’s strategic advantage in AI engineering to create powerful collaborations. These could include partnerships with the Georgia Tech Research Institute, for maximizing societal impact, and Tech’s 10 interdisciplinary research centers as well as its three NSF-funded AI institutes, for augmenting academic and policy impact.

“The AI Hub will empower all AI-related activities, from foundational research to applied AI projects, joint AI labs, AI incubators, and AI workforce development; it will also help shape AI policies and improve understanding of the social implications of AI technologies,” Van Hentenryck explained. “A key aspect will be to scale many of AI4OPT’s initiatives to Georgia Tech’s AI ecosystem more generally — in particular, its industrial partner and workforce development programs, in order to magnify societal impact and democratize access to AI and the AI workforce.”

Van Hentenryck is also thinking about AI’s technological implications. “AI is a unifying technology — it brings together computing, engineering, and the social sciences. Keeping humans at the center of AI applications and ensuring that AI systems are trustworthy and ethical by design is critical,” he added.

In its first year, the AI Hub will focus on building an agile and nimble organization to accomplish the following goals:

facilitate, promote, and nurture use-inspired research and innovative industrial partnerships;

translate AI research into impact through AI engineering and entrepreneurship programs; and

develop sustainable AI workforce development programs.

Additionally, the AI Hub will support new events, including AI-Tech Fest, a fall kickoff for the center. This event will bring together Georgia Tech faculty, as well as external and potential partners, to discuss recent AI developments and the opportunities and challenges this rapidly proliferating technology presents, and to build a nexus of collaboration and innovation.

Shelley Wunder-Smith

Director of Research Communications

Secretary of Energy Announces a Tri-City Alliance With Georgia Tech for Scalable, Equitable, and Innovative Clean Energy Solutions

Apr 24, 2024 — Atlanta, GA

From the Left: SEI Executive Director Tim Lieuwen, U.S. Rep. Nikema Williams, Georgia Tech Student Azell Francis, Secretary Jennifer Granholm, Mayor Andrew Dickens

On a recent visit to the Georgia Tech campus, Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm announced that a tri-city alliance of Atlanta, Decatur, and Savannah in partnership with Georgia Tech will receive funding to drive clean energy solutions.

The funding is part of DOE’s Energy Future Grants program, and the Atlanta-Decatur-Savannah partners will receive $500,000 during the planning phase to develop initiatives, policies, and tools to promote green energy deployment in their communities. In total, the grants will provide $27 million in financial and technical assistance to support strategies that increase resiliency and improve access to affordable clean energy. The team will compete with other recipients for additional funding in subsequent phases of the program.

The Georgia Energyshed (G-SHED) team, led by Richard Simmons of the Strategic Energy Institute, will partner with the tri-city team in this project. The modeling and simulation-driven analysis from G-SHED will be used by the Tri-City Alliance project to develop deployment-ready blueprints of clean energy innovations focused on community benefits.

The G-SHED team, formed through another DOE grant, is developing a metropolitan energy planning organization informed by an integrated modeling effort that includes technical, social, and community inputs. Georgia Tech is collaborating with the Atlanta Regional Commission and the Southface Institute in this project.

Granholm said announcing the funding at Georgia Tech was fitting because its tools “are going to be magnificent for this project for communities to decide the best path for them based on data.” Atlanta Mayor Andrew Dickens, U.S. Rep. Nikema Williams, and several other dignitaries were present during the announcement. Secretary Granholm toured parts of the Georgia Tech campus including the Carbon Neutral Energy Solutions building during her visit.

“It’s exciting when the Secretary of Energy makes a special trip to campus to announce a new Award. I appreciate Secretary Granholm and the Department of Energy for enabling this innovative energy partnership with Atlanta, Decatur, and Savannah,” said Tim Lieuwen, executive director of the Strategic Energy Institute.

From the Left: Richard Simmons (SEI), Jordann Shields (SEI), Chandra Farley (City of Atlanta), John R Seydel (City of Atlanta), Catherine Mercier-Baggett (Southeast Sustainability Directors Network), Rachel Usher (Southeast Sustainability Directors Network), Tony Powers (City of Decatur), Andrea Arnold (City of Decatur), Tim Lieuwen (SEI)

Priya Devarajan || SEI Communications Program Manager

James Stroud Named Early Career Fellow by Ecological Society of America

Apr 30, 2024 —

James T. Stroud has been named an Early Career Fellow by the Ecological Society of America.

He joins the ranks of nine newly appointed ESA Fellows and ten 2024-2028 ESA Early Career Fellows, elected for "advancing the science of ecology and showing promise for continuing contributions" and recently confirmed by the organization's Governing Board.

Stroud, an Elizabeth Smithgall Watts Early Career Assistant Professor in the School of Biological Sciences, is an integrative evolutionary ecologist who investigates how ecological and evolutionary processes may underlie patterns of biological diversity at the macro-scale.

He primarily studies lizards and his research is highly multidisciplinary, combining field studies with macro-ecological and evolutionary comparative analyses. Stroud’s current interests are particularly focused on measuring natural selection in the wild, often taking advantage of non-native lizards as natural experiments in ecology and evolution.

Earlier this month, Stroud presented his recent work at the inaugural College of Sciences Frontiers in Science: Climate Action Conference and Symposium, joining more than 20 faculty experts and 100 stakeholders from across all six colleges at Georgia Tech to discuss climate change, challenges, and solutions.

Stroud joined the Georgia Tech faculty in August 2023. He earned a Ph.D. in Ecology and Evolution from Florida International University.

"I am thrilled to recognize the exceptional contributions of our newly selected Fellows and Early Career Fellows,” says ESA President Shahid Naeem. “Their groundbreaking research, unwavering commitment to mentoring and teaching and advocacy for sound science in management and policy decisions have not only advanced ecological science but also inspired positive change within our community and beyond. We celebrate their achievements and eagerly anticipate the profound impacts they will continue to make in their careers."

ESA will formally acknowledge and celebrate its new Fellows for their exceptional achievements during a ceremony at ESA’s 2024 Annual Meeting in Long Beach, California.

About ESA Fellowships

ESA established its Fellows program in 2012 with the goal of honoring its members and supporting their competitiveness and advancement to leadership positions in the Society, at their institutions, and in broader society. Past ESA Fellows and Early Career Fellows are listed on the ESA Fellows page.

About ESA

The Ecological Society of America, founded in 1915, is the world’s largest community of professional ecologists and a trusted source of ecological knowledge, committed to advancing the understanding of life on Earth. The 8,000 member Society publishes six journals and a membership bulletin and broadly shares ecological information through policy, media outreach, and education initiatives. The Society’s Annual Meeting attracts 4,000 attendees and features the most recent advances in ecological science. Visit the ESA website at https://www.esa.org.

Jess Hunt-Ralston

Director of Communications

College of Sciences at Georgia Tech

Mayda Nathan

Ecological Society of America

Georgia Tech’s Space Research Initiative Hosts Yuri’s Day Symposium

Apr 30, 2024 —

April 12 is a significant date in the history of exploration, as it marks the first space flight of a human, Yuri Gagarin, in 1961. This year on April 12, the Georgia Tech Space Research Initiative (Space RI) hosted an event highlighting the Institute’s interdisciplinary space research. The Yuri’s Day Symposium was Space RI’s first public event.

A multidisciplinary initiative, the Space RI brings together faculty, researchers, and students from across campus who share a passion for space exploration. Their combined research explores a broad array of space-related topics, all considered from a human perspective.

“Launching Georgia Tech’s Space Research Initiative reinforces our commitment to advancing our understanding of space and our universe,” said Executive Vice President for Research Chaouki Abdallah. “It is also a testament to Georgia Tech's unwavering dedication to pushing the limits of what is possible and to fostering innovations that benefit humankind.”

The symposium was organized by Glenn Lightsey, interim executive director of the Space RI, and the Space RI steering committee, which consists of representatives from the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) and the Colleges of Engineering, Computing, and Sciences, the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts, and the Scheller College of Business. The day began with remarks from Research leadership and an overview of the Space RI and its mission. “This is an exciting time for space exploration at Georgia Tech and across the world,” Lightsey said. “Space research is a critical part of solving our world’s most challenging problems and improving life for everyone on Earth.”

Space research and exploration yield many societal benefits that improve life on Earth and even foster economic growth. These advances include rapidly evolving technologies, improvements in medicine, and the development of enhanced materials — such as self-healing materials and those designed for extreme environments. Additionally, space research provides essential tools, data, and insights for climate scientists.

Sessions and panels throughout the day covered space science, space media, NASA’s Moon to Mars program, GTRI’s space research program, commercial space initiatives, and space in popular culture. A.C. Charania, NASA’s chief technologist and a Georgia Tech alumnus, delivered the keynote address. He shared insights into his work at NASA and Moon to Mars.

Following the symposium, the Space RI hosted a “star party” at the Georgia Tech Observatory. People of all ages gathered at the event, where they could use the observatory’s telescope to observe the moon, Jupiter, and the Orion Nebula, an immense cloud of dust and gas from which new stars are born.

“It was a clear night, and we were able to view the lunar terminator — the boundary where the sun is setting on the moon — which accentuates craters and mountains,” said Lightsey. “It was exciting to officially launch our initiative on a day when the world celebrated space exploration and the star party was a fantastic way to end our event.”

In July 2025, the Space RI will transition into one of Georgia Tech’s Interdisciplinary Research Institutes. Learn more about the initiative at space.gatech.edu.

Sign up to receive space news and event updates from the Space RI.

Laurie Haigh

Research Communications

David Bridges Receives Fulbright Specialist Award to Slovak Republic at Digital Coalition

Apr 26, 2024 —

David Bridges, vice president of Georgia Tech's Enterprise Innovation Institute.

The U.S. Department of State and the Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board are pleased to announce that David Bridges, vice president of the Georgia Institute of Technology's Enterprise Innovation Institute, has received a Fulbright Specialist Program award.

Bridges, who was named Fulbright Specialist in February of 2024, will complete a project at the Digital Coalition in the Slovak Republic that aims to exchange knowledge and establish partnerships benefiting participants, institutions, and communities both in the U.S. and overseas through a variety of educational and training activities within Public Administration.

Bridges is one of over 400 U.S. citizens who share expertise with host institutions abroad through the Fulbright Specialist Program each year. Recipients of Fulbright Specialist awards are selected on the basis of academic and professional achievement, demonstrated leadership in their field, and their potential to foster long-term cooperation between institutions in the U.S. and abroad.

The Fulbright Program is the flagship international educational exchange program sponsored by the U.S. government and is designed to build lasting connections between the people of the United States and the people of other countries. The Fulbright Program is funded through an annual appropriation made by the U.S. Congress to the U.S. Department of State. Participating governments and host institutions, corporations, and foundations around the world also provide direct and indirect support to the Program, which operates in over 160 countries worldwide.

Since its establishment in 1946, the Fulbright Program has given more than 400,000 students, scholars, teachers, artists, and scientists the opportunity to study, teach and conduct research, exchange ideas, and contribute to finding solutions to shared international concerns.

Fulbrighters address critical global issues in all disciplines, while building relationships, knowledge, and leadership in support of the long-term interests of the United States. Fulbright alumni have achieved distinction in many fields, including 60 who have been awarded the Nobel Prize, 88 who have received Pulitzer Prizes, and 39 who have served as a head of state or government.

For further information about the Fulbright Program or the U.S. Department of State, please visit eca.state.gov/fulbright or contact the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs Press Office by telephone 202.632.6452 or e-mail eca-press@state.gov.

Péralte C. Paul

peralte@gatech.edu

404.316.1210

New Science and Medical Research Hub Opens in Atlanta

Apr 25, 2024 —

Trammell Crow Company delivers first phase of Georgia Tech district devoted to advancing sciences that improve the human condition.

Georgia Institute of Technology and the Trammell Crow Company are transforming Atlanta’s booming skyline with the launch of the first phase of Science Square, a pioneering mixed-use development dedicated to biological sciences and medical research and the technology to advance those fields. A ribbon-cutting ceremony is planned for April 25.

“The opening of Science Square’s first phase represents one of the most exciting developments to come to Atlanta in recent years,” said Ángel Cabrera, president of Georgia Tech. “The greatest advances in innovation often emerge from dense technological ecosystems, and Science Square provides our city with its first biomedical research district, which will help innovators develop and scale their ideas into marketable solutions.”

Science Square’s first phase includes Science Square Labs, a 13-story purpose-built tower with state-of-the-art infrastructure to accommodate wet and dry labs and clean room space. To promote overall energy efficiency as well as sustainability, the complex houses a massive 38,000-square-foot solar panel. The solar panel system is in addition to an energy recovery system that extracts energy from the building’s exhaust air and returns it to the building’s HVAC system, reducing carbon dioxide emissions. Electrochromic windows, which tint during the day to block ultraviolet rays and steady the temperature while also controlling the environment — key in research labs — are also featured throughout the building.

Equipped with technologically advanced amenities and infrastructure, Science Square Labs serves as a nexus for groundbreaking research, enabling collaboration between academia, industry, and startup ventures. Portal Innovations, a company specializing in life sciences venture development, is among the first tenants to establish operations at Science Square, as Atlanta takes center stage as the country’s top city for research and development employment growth.

The opening of the complex’s first phase, just south of Georgia Tech’s campus and totaling 18 acres, also features retail space and The Grace Residences developed by High Street Residential, TCC's residential subsidiary. The 280-unit multifamily tower, already welcoming tenants, is named in honor of renowned Atlanta leader and Georgia State Representative Grace Towns Hamilton who spent many years championing this community.

Beyond its scientific endeavors, Science Square embodies Georgia Tech’s commitment to uplifting the local community. By collaborating with organizations like Westside Works, Science Square aims to empower residents through targeted workforce development initiatives and economic opportunities.

“This mixed-use development adds immense value to Atlanta’s west side and will lead the development of pioneering medical advances with the power to improve and save lives,” President Cabrera added.

Director, Media Relations

Georgia Institute of Technology

Senior Media Relations Representative

New Approach Could Make Reusing Captured Carbon Far Cheaper, Less Energy-Intensive

Apr 25, 2024 — Atlanta, GA

A new electrochemical reactor design developed with Marta Hatzell by postdoctoral scholar Hakhyeon Song (middle) and Ph.D. students Carlos Fernández and Po-Wei Huang (seated) converts carbon dioxide removed from the air into useful raw material. Their approach is cheaper and simpler while requiring less energy, making it a promising tool to improve the economics of direct air capture systems. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

Engineers at Georgia Tech have designed a process that converts carbon dioxide removed from the air into useful raw material that could be used for new plastics, chemicals, or fuels.

Their approach dramatically reduces the cost and energy required for these direct air capture (DAC) systems, helping improve the economics of a process the researchers said will be critical to addressing climate change.

The key is a new kind of catalyst and electrochemical reactor design that can be easily integrated into existing DAC systems to produce useful carbon monoxide (CO) gas. It’s one of the most efficient such design ever described in scientific literature, according to lead researcher Marta Hatzell and her team. They published details April 16 in Energy and Environmental Science, a top journal for energy-related research.

Joshua Stewart

College of Engineering

Why Can’t Robots Outrun Animals?

May 02, 2024 —

Can this small robot outrun a spider? Photo Credit: Animal Inspired Movement and Robotics Lab, CU Boulder.

Robots that can run, jump, and even talk have shifted from the stuff of science fiction to reality in the past few decades. Yet even in robots specialized for specific movements like running, animals are still able to outmaneuver the most advanced robotic developments.

Georgia Tech’s Simon Sponberg recently collaborated with researchers at the University of Washington, Simon Fraser University, University of Colorado Boulder, and Stanford Research Institute to answer one deceptively complex question: Why can’t robots outrun animals?

“This work is about trying to understand how, despite have some really amazing robots, there still seems to be a gulf between the capabilities of animal movement and what we can engineer,” says Sponberg, who is Dunn Family Associate Professor in the School of Physics and School of Biological Sciences.

Recently published in Science Robotics, their study systematically examines a suite of biological and robotic runners to figure out how to further advance our best robotic designs.

“In robotics design we are often very component focused — we are used to having to establish specifications for the parts that we need and then finding the best component solution,” said Sponberg, who also serves on the executive committee for Georgia Tech's Neuro Next Initiative. “This is of course not how evolution works. We wondered if we systematically analyzed the performance of animals in the same component way that we design robots, if we might see an obvious gap.”

The gap turns out not to be in the function of individual robotic components, but rather the ability of those components to work together in the seamless way biological components do, highlighting a field of opportunity for new research in robotic development.

“This means that the frontier is not necessarily figuring out how to design better motors or sensors or controllers,” says Sponberg, “but rather how to integrate them together — this is where biology really excels.”

Read more about man versus machine and the future of bioinspired robotics here.

Audra Davidson

Research Communications Program Manager

Neuro Next Initiative

Neurotech Moonshot: Georgia Tech Researcher Shares Impact of BRAIN Initiative in Congressional Briefing

Apr 24, 2024 —

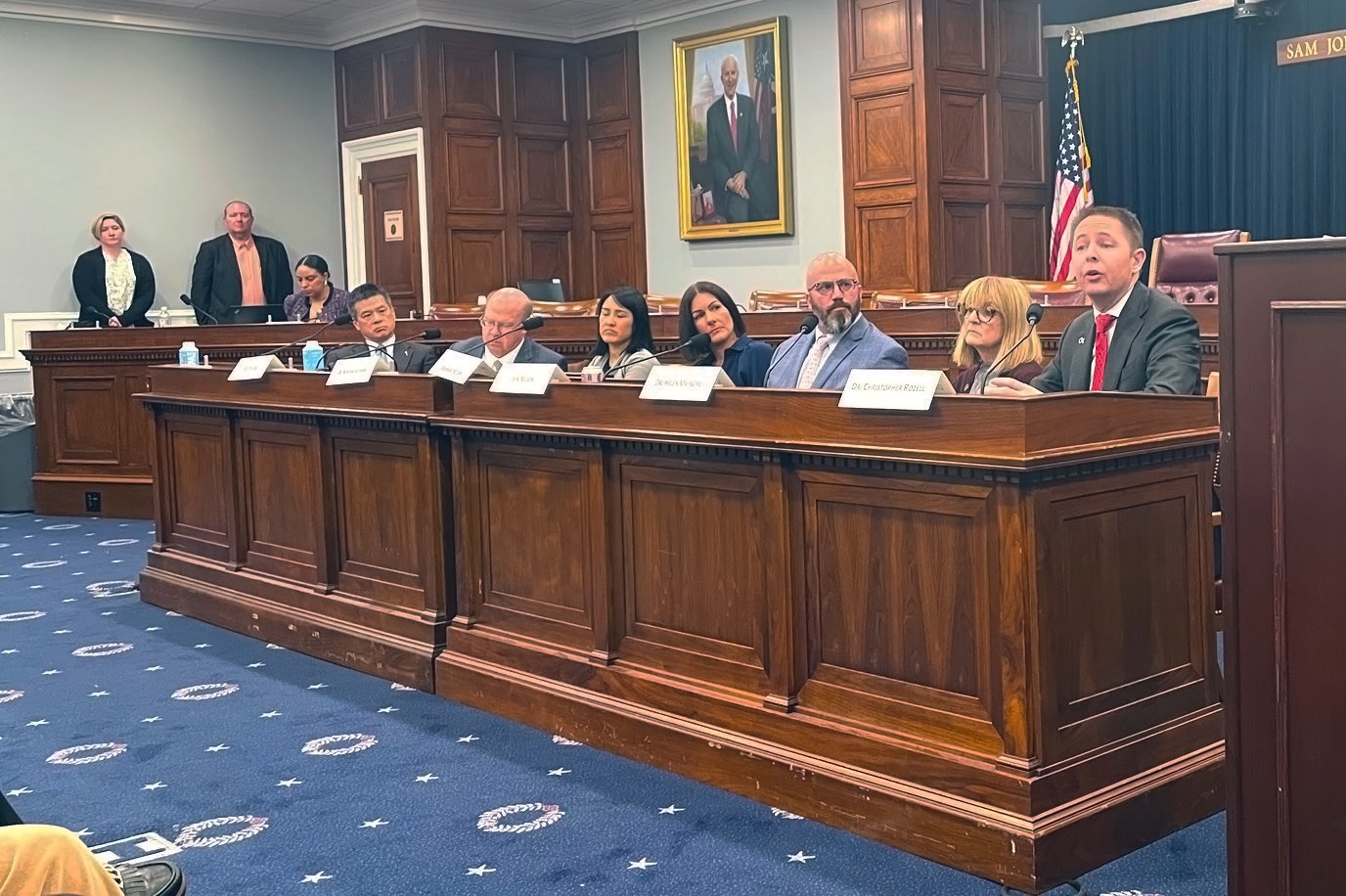

Rozell was joined by BRAIN Initiative Director John J. Ngai, clinical collaborators, and a family whose lives have been transformed by this work.

For the past 10 years, the National Institutes of Health have led an unprecedented effort to revolutionize our understanding of the human brain. The aptly named BRAIN (Brain Research Through Advancing Neurotechnologies) Initiative has led to remarkable technological advancements, insights into the structure and function of the brain, and budding therapies.

Recently, School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) Professor Chris Rozell traveled to Washington, D.C. to share the impact of his BRAIN Initiative research with U.S. Congressional offices — and offer insights on how critical this program is to society. The briefing took on a particular urgency because BRAIN Initiative funding was cut over 40% this year, and future funding appears to be in jeopardy in the current federal budget climate.

“The millions of patients suffering with intractable neurologic disorders and mental illness deserve a moonshot to develop new solutions for their conditions,” said Rozell, who also holds the Julian T. Hightower Chair in ECE and serves on the executive committee for Georgia Tech’s Neuro Next Initiative. “You can't get to the moon with a paper plane, and you can’t get there without a map. The BRAIN Initiative is a vital program because it's one of the few places that brings together interdisciplinary teams that include the scientists who have been building maps of brain circuits and the engineers who have been building rockets to understand and intervene with those circuits.

“I'm proud to have had the chance to represent not only our own research, but the incredible community here at Georgia Tech and around the country working to understand many different aspects of the brain, developing new neurotechnologies, and advancing therapies for neurologic disorders.”

Interdisciplinary impacts

“The main message we presented to Congress is that the interdisciplinary combination of rigorous science and technical innovation can have enormous societal impact over the next few decades,” said Rozell.

A stark example of that impact was published in Nature this past fall. In this research, Rozell and his collaborators at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Emory University School of Medicine identified the first known biomarker of disease recovery with deep brain stimulation in treatment-resistant depression.

“The fact that an engineer can advance clinical therapies is a testament to the new era we're in,” says Rozell, “where disciplinary boundaries are fading, and technological innovation accelerates our scientific and translational breakthroughs.”

This research served as a focal point of the congressional briefing, where Rozell presented with BRAIN Initiative Director John J. Ngai, clinical collaborators, and a family whose lives have been transformed by this work.

“Events like last week are dream come true,” shared Jon Nelson, who was treated with deep brain stimulation as part of the study and presented with Rozell in D.C. After living through 10 years of debilitating, treatment-resistant depression, Nelson says “remission of depression still doesn't feel real. It's been a year and a half, and I still am in awe every single day.

“The fact that I have come out of this study and found that the disease is purely an electrical deficiency in my brain has fueled me to completely pulverize the stigma of mental illness,” Nelson explained. “When you have an opportunity to go speak to Congress — that’s about as great of a platform as you can get for that. Being able to put a face to what the BRAIN Initiative funding can do for people was just amazing.”

When meeting with local representatives, Rozell also relayed his work as co-executive leader of the Neuro Next Initiative, a budding Interdisciplinary Research Institute at Georgia Tech.

“I was thrilled to highlight that Georgia Tech is leading the charge with the Neuro Next Initiative, which will evolve into a full Interdisciplinary Research Institute in 2025,” said Rozell. “Georgia Tech has the ingredients to become a leading center for modern technology-driven interdisciplinary brain research and workforce development.

“This visit was a reminder to me that research funding is not guaranteed and it’s important to keep communicating the critical value that research plays in advancing our understanding, training our workforce, fueling our economy, and ultimately making a better tomorrow for society.”

Rozell presented to members of U.S. Congress as well as local representatives during his visit.

Georgia Tech Engineering Professor Chris Rozell shared his research and the impacts of the past decade of brain research funded by the NIH BRAIN Initiative with Congress.

Audra Davidson

Research Communications Program Manager

Neuro Next Initiative