LLS Funds Immunoengineers and Cancer Specialists to Tackle Health Disparities

Nov 21, 2024 —

Jean Louise Koff and Ankur Singh

A multi-institutional research initiative aims to address lymphoma survival disparities in African American and EBV-infected patients.

A new interdisciplinary initiative with researchers at Georgia Tech, Emory University, MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Weill Cornell Medical aims to address the knowledge gap in lymphomas — particularly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the most common form of blood cancer. Survival rates for DLBCL are lower among African American patients and those with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is prevalent in Latin America. The team uses immunoengineering tools to facilitate this discovery.

Tackling Health Disparities in Lymphoma Treatment

To address these health disparities, the team combines expertise in cancer biology and immunoengineering. At Georgia Tech, Ankur Singh works with oncologists and cancer biologists from partner institutions to create innovative cancer technologies, such as lab-grown, lymph node-mimicking models of DLBCL tumors. Singh is Carl Ring Family Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering (BME) and directs the Center for Immunoengineering. These models will mimic the tumor environments in lymphoma from African American patients and model specific mutations prevalent in these patients. Researchers will observe how various genetic changes work in concert with the immune system to impact a tumor's response to treatments.

“We want to understand the full makeup of these tumors; not just the cancer cells but the surrounding supportive cells and proteins,” said Singh, who serves as co-investigator for LLS SCOR. “This study will help us pinpoint which parts of the tumor are critical for its survival and how we can disrupt those mechanisms, including the immune cells.”

Challenges for Understanding Tumor Biology in High-Risk Groups

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common form of blood cancer. While many patients respond well to standard therapies, a significant portion — including a disproportionate number of African Americans and individuals with EBV-related conditions, experience poorer outcomes. The reasons behind these disparities are still largely unknown. Current barriers include a lack of diverse representation in research studies and a paucity of engineered technologies dedicated to understanding cancers in patients from underrepresented backgrounds.

"Most lymphoma studies don't include nearly enough African American or Hispanic patients," said Jean Koff, lead investigator and associate professor of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University’s Winship Cancer Institute. “This means we are likely missing key insights into the unique biology and treatment needs of these populations.”

A Collaboration Focused on Advancing Lymphoma Research and Care

This new initiative, funded by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society's Specialized Center of Research (SCOR) Program, will analyze a comprehensive collection of DLBCL tumor samples that includes many cases from Black and Hispanic patients. By examining genetic differences and tumor structures, the researchers hope to identify the factors most important for improving therapy for these groups.

“This program is groundbreaking because it addresses both biological and structural barriers in treatment, leveraging the latest bioengineered technologies,” Singh noted. “We’re looking at factors that have been overlooked for too long in cancer research, especially in high-risk communities.”

To explore the composition and diversity of cells within tumors of African American patients and better understand how they grow and respond to treatments, the team leverages the expertise of Ahmet Coskun. Coskun is a Georgia Tech immunoengineer known for his innovative approaches to understanding the immune response to cancer. An assistant professor in BME, Coskun holds the Bernie Marcus Early Career Professorship. He and his team use advanced imaging techniques and engineering principles to analyze tumor microenvironments in unprecedented detail. By examining how different immune cells interact with cancer cells, they hope to uncover the complexities of tumor biology and identify factors that contribute to treatment resistance.

This five-year, multi-million-dollar LLS SCOR award is the culmination of years of collaboration among leading researchers in the field of lymphoma. Singh, with colleagues Koff, Coskun, Christopher Flowers at MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Cornell Medicine’s Ari Melnick, Ethel Cesarman, and Leandro Cerchietti, are fostering a partnership in lymphomas and EBV-related cancers, which is instrumental in advancing research on lymphoma treatment health disparities. Their longstanding partnership reflects a commitment to addressing the complex challenges different populations face when battling deadly cancers.

"With this unique partnership, leveraging new cancer technologies, biology, and clinical expertise, we hope to make breakthroughs in lymphoma research and begin to address health disparities in lymphoma at multiscale levels,” said Melnick, a co-lead for LLS SCOR and Gebroe Family Professor of Hematology and Oncology at New York’s Weill Cornell Medicine.

The group also played a significant role in organizing, moderating, and presenting at the inaugural conference “Health Disparities in Hematologic Malignancies: From Genes to Outreach,” held in May 2023 in New York. The conference served as a vital platform for discussing the latest research, sharing best practices, and highlighting the importance of outreach initiatives aimed at improving care for underserved populations.

"The research will provide a unique window into the intricate structure of lymphomas and how these complexities influence treatment,” said Flowers, a physician-scientist and division head of Cancer Medicine at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. “By studying lymphoma microenvironments in patient tissues and organoids, we can begin addressing health disparities in lymphoma, identifying why certain populations may respond differently to therapies. No other technology currently provides this level of insight or potential for tailored patient care."

This unique research collaboration is crucial, as understanding tumor heterogeneity can inform the development of more personalized treatment strategies, particularly for underserved communities that often face disparities in cancer care. By integrating engineering with oncology, the team hopes to create more effective therapies tailored to individual patient profiles, ultimately aiming to improve outcomes for all lymphoma patients. This multi-site collaboration aims to fast-track the development of therapies against lymphomas in African Americans and individuals with EBV-related conditions and eventually bring them to clinical trials.

Project Title: Translating molecular profiles into treatment approaches to target disparities in lymphoma

(Funding and award period: $5 million, October 1, 2024 - September 30, 2029)

Related reading: Georgia Tech-Emory Collaboration on Cancer Disparity in African Americans Gets NIH Boost

By: Savannah Williamson

Mapping Protein Interactions to Fight Lung Cancer: Coskun Pioneering New Field of Research

Nov 21, 2024 —

Ahmet Coskun's lab has developed iseqPLA to map protein interactions.

As Ahmet F. Coskun and his team of researchers continue their mission to create a 3D atlas of the human body, mapping cells and tissues, they’re making discoveries that could lead to better treatments for the most common type of lung cancer.

While they’re at it, they’re pioneering new fields of research, and possibly spinning the work into a new commercial venture.

Last year, Coskun and his team introduced a new study in “single cell spatial metabolomics,” which explores the distribution of small molecules — metabolites — within tissues and organs. Now they’re spearheading “spatial interactomics,” a research area concerned with interactions between various biomolecules inside of individual cells.

To study these interactions, they’ve developed an innovative technique, or tool, to better understand why non-small cell lung cancer, or NSCLC, resists treatment in so many patients. They call it the “intelligent sequential proximity ligation assay,” or iseqPLA.

“It’s a smart test that can look at proteins and how they interact with each other in space,” said Coskun, Bernie Marcus Early Career Professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University.

“Basically, we’re the first to create a new research area on spatial protein-protein interactions, which can tell us more about cell types and their functions,” said Coskun. “With spatial interactomics, we can validate how cells physically touch, sense, and regulate nearby cells through the interaction of pairs of proteins.”

So, the immediate goal of spatial interactomics is to investigate how protein-protein interactions drive drug resistance in NSCLC. And iseqPLA allows researchers to visualize how it’s all happening at the subcellular level. Coskun’s team described its work recently in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering. He’s also forming a company to commercialize the technology.

Smarter Tools

Drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs, like Osimertinib) have been successful in treating people with NSCLC. But many patients who initially respond well to the regimen, eventually develop a resistance. Protein interactions, a molecular kind of crosstalk, are a prime suspect in causing this resistance.

Proteins interact with each other all the time, and this mingling controls how cells grow, divide, or survive. Coskun and his team want to see how these interactions change in response to cancer treatment, and iseqPLA shows them, essentially attaching glowing tags to proteins, lighting up their locations and interactions under a microscope.

“Think of it like a super detailed map showing how different proteins in a cell are connected,” Coskun said.

The iseqPLA can examine 47 protein interactions in a single sample, which saves a lot of time (and resources) when compared to older methods, which look at two to three interactions at a time.

The researchers also created a computer model to analyze the spatial data they collected from iseqPLA, identifying patterns in protein interactions to help predict whether a cell was responding to a treatment or developing resistance.

“We showed that the test works not only in lab-grown cells but also in tissues from mice and humans,” Coskun said. “It can really help us understand how patients respond to certain treatments.”

Building a Spatial Omics Market

Going forward, Coskun aims to enhance iseqPLA to study interactions among RNA, proteins, and metabolites, as well as the RNA, proteins, metabolites, etc., and other subcellular dynamics. He also hopes to get the technology into the hands of other researchers.

“We believe it will be a groundbreaking tool,” he said.

With that in mind, Coskun is planning to form a startup company called SpatAllize. He’s working with VentureLab, the nonprofit organization at Georgia Tech that provides entrepreneurship programs for students and faculty.

“We are currently performing customer interviews and forming a strategy for a viable plan towards the marketplace,” he said.

He also plans to expand iseqPLA’s utility into other areas of research, focusing on how protein interactions influence the immune system, the heart, and brain health. His team is also developing a spatial interactomics robot that integrates iseqPLA with advanced imaging and automated deep learning.

“This will allow us to map all molecules within cells and tissues for an even better understanding of drug-cell interactions, particularly in cancer treatment planning,” Coskun said.

CITATION: Shuangyi Cai, Thomas Hu, Abhijeet Venkataraman, Felix G. Rivera Moctezuma, Efe Ozturk, Nicholas Zhang, Mingshuang Wang, Tatenda Zvidzai, Sandip Das, Adithya Pillai, Frank Schneider, Suresh S. Ramalingam, YouTake Oh, Shi-Yong Sun, and Ahmet F. Coskun. “Spatially resolved subcellular protein–protein interactomics in drug-perturbed lung-cancer cultures and tissues.” Nature Biomedical Engineering.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-024-01271-x

FUNDING: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant Nos. P50CA217691, P30CA138292, and R33CA291197; and the National Science Foundation, grant No. R35GM151028. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any funding agency.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Coskun, Cai, and Hu declare a patent application related to the spatial-signaling interactomics assay (U.S. Provisional 63/399,427 and U.S. Application No. 18/452,178).

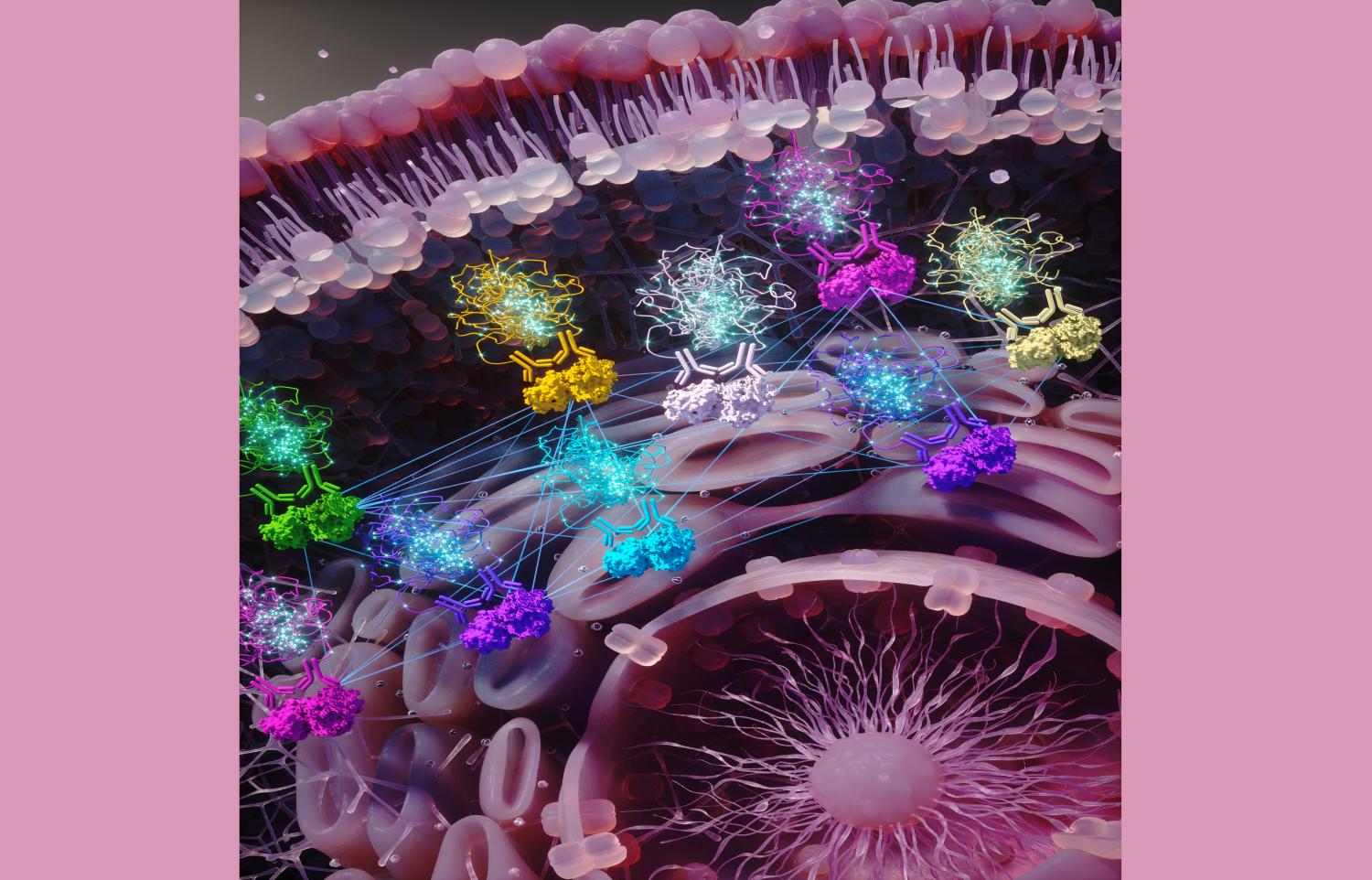

An artistic rendering of sub-cellular activity: The cell membrane is seen at the top, nucleus on the bottom/right. Protein pairs are being targeted by antibodies (sets of two). Then antibodies are linked to DNA pieces that glow when proteins were found to be closely interacting with each other. The glowing fluorescence DNA signal is then imaged by a microscope indicating the spatial locations of protein interactions as dots, which researchers use to generate graph models. The straight lines connecting the antibody and protein pairs indicate their graph wiring that gets altered in drug resistance.

From Mars to the Stars: James Wray Wins Simons Fellowship to Study Interstellar Objects

Nov 22, 2024 —

'Oumuamua at the edges of our solar system (Artist's Rendition, NASA)

In 2017, a long, oddly shaped asteroid passed by Earth. Called ‘Oumuamua, it was the first known interstellar object to visit our solar system, but it wasn’t an isolated incident — less than two years later, in 2019, a second interstellar object (ISO) was discovered.

“‘Oumuamua was found passing just 15 million miles from Earth — that’s much closer than Mars or Venus,” says James Wray. “But it was formed in an entirely different solar system. Studying these objects could give us incredible insight into extrasolar planets, and how our planet fits into the universe.”

Wray, a professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Georgia Tech, has just been awarded a Simons Foundation Pivot Fellowship to do just that. Pivot Fellowships are among the most prestigious sources of funding for cutting-edge research, and support leading researchers who have the deep interest, curiosity and drive to make contributions to a new discipline.

Wray has primarily studied the geoscience of Mars. He will leverage knowledge of nearby planets to understand ISOs and planets much farther away. “I want to understand how planets got to be the way they are, and if they could have ever hosted life,” he explains. “Extrasolar planets give us many more places to ask those questions than our solar system does, but they're too distant to visit with spacecraft. ISOs provide a unique opportunity to explore other solar systems without leaving our own.”

The Fellowship will provide salary support as well as funding for research, travel, and professional development. “Seed funds like this are so valuable,” says Wray. “I’m incredibly grateful to the Simons Foundation. I’d also like to thank Georgia Tech for its support,” he adds, sharing that the Center for Space Technology and Research supported a related research effort at the University of Hawaii earlier this year. “My mentor and I were able to spend some of that time improving our Pivot Fellowship proposal, which played a critical role in securing this Fellowship.”

In search of ISOs

Wray will study small solar system bodies like asteroids and comets to decode the processes of planet formation and space weathering, and will analyze data from the 2017 and 2019 ISOs.

He will also work alongside collaborators including Karen Meech of the University of Hawaii, who led the paper characterizing ‘Oumuamua, to conceptualize what an intercept mission might look like.

“We still have a lot of questions regarding ISOs,” he says. “Hundreds of papers have already been written about them, but we still don't know the answers.” One key mystery is the composition of the bodies: both the 2017 and 2019 objects were compositionally different from those in our solar system.

“Are they inherently different from the bodies in our solar system, or did the long journey to our solar system make them that way? Is our solar system different from others?” Wray asks. “We could answer so many questions with even a simple picture of the next ISO that comes close enough for us to intercept with spacecraft.”

A cosmic timeline

While there is no guarantee that another ISO might be spotted in our solar system, the timing is opportune — upcoming telescope surveys are poised to detect such interstellar objects. “In mid-2025, when I will start this Fellowship, the new Rubin Observatory will begin scanning the entire sky,” Wray says. “It has the potential to discover up to several new ISOs per year.”

“ISO visits are always brief,” he adds, “so the research needs to be in place for when one is spotted.” If an interstellar object is detected, Wray and Meech will be poised to leverage specialized telescopes in Hawaii, along with others worldwide, to better understand it, studying its size, shape, and composition — and potentially sending spacecraft to image it.

“We might never find another ISO — or they might be the key to imminent breakthroughs in understanding our place in the galaxy,” Wray adds. “I'm extremely grateful to the Simons Foundation for the flexibility to pursue this research at whatever pace the cosmos allows.”

Professor James Wray

Written by Selena Langner

Minority English Dialects Vulnerable to Automatic Speech Recognition Inaccuracy

Nov 15, 2024 —

The Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) models that power voice assistants like Amazon Alexa may have difficulty transcribing English speakers with minority dialects.

A study by Georgia Tech and Stanford researchers compared the transcribing performance of leading ASR models for people using Standard American English (SAE) and three minority dialects — African American Vernacular English (AAVE), Spanglish, and Chicano English.

Interactive Computing Ph.D. student Camille Harris is the lead author of a paper accepted into the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) this week in Miami.

Harris recruited people who spoke each dialect and had them read from a Spotify podcast dataset, which includes podcast audio and metadata. Harris then used three ASR models — wav2vec 2.0, HUBERT, and Whisper — to transcribe the audio and compare their performances.

For each model, Harris found SAE transcription significantly outperformed each minority dialect. The models more accurately transcribed men who spoke SAE than women who spoke SAE. Members who spoke Spanglish and Chicano English had the least accurate transcriptions out of the test groups.

While the models transcribed SAE-speaking women less accurately than their male counterparts, that did not hold true across minority dialects. Minority men had the most inaccurate transcriptions of all demographics in the study.

“I think people would expect if women generally perform worse and minority dialects perform worse, then the combination of the two must also perform worse,” Harris said. “That’s not what we observed.

“Sometimes minority dialect women performed better than Standard American English. We found a consistent pattern that men of color, particularly Black and Latino men, could be at the highest risk for these performance errors.”

Addressing underrepresentation

Harris said the cause of that outcome starts with the training data used to build these models. Model performance reflected the underrepresentation of minority dialects in the data sets.

AAVE performed best under the Whisper model, which Harris said had the most inclusive training data of minority dialects.

Harris also looked at whether her findings mirrored existing systems of oppression. Black men have high incarceration rates and are one of the people groups most targeted by police. Harris said there could be a correlation between that and the low rate of Black men enrolled in universities, which leads to less representation in technology spaces.

“Minority men performing worse than minority women doesn’t necessarily mean minority men are more oppressed,” she said. “They may be less represented than minority women in computing and the professional sector that develops these AI systems.”

Harris also had to be cautious of a few variables among AAVE, including code-switching and various regional subdialects.

Harris noted in her study there were cases of code-switching to SAE. Speakers who code-switched performed better than speakers who did not.

Harris also tried to include different regional speakers.

“It’s interesting from a linguistic and history perspective if you look at migration patterns of Black folks — perhaps people moving from a southern state to a northern state over time creates different linguistic variations,” she said. “There are also generational variations in that older Black Americans may speak differently from younger folks. I think the variation was well represented in our data. We wanted to be sure to include that for robustness.”

TikTok barriers

Harris said she built her study on a paper she authored that examined user-design barriers and biases faced by Black content creators on TikTok. She presented that paper at the Association of Computing Machinery’s (ACM) 2023 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Works.

Those content creators depended on TikTok for a significant portion of their income. When providing captions for videos grew in popularity, those creators noticed the ASR tool built into the app inaccurately transcribed them. That forced the creators to manually input their captions, while SAE speakers could use the ASR feature to their benefit.

“Minority users of these technologies will have to be more aware and keep in mind that they’ll probably have to do a lot more customization because things won’t be tailored to them,” Harris said.

Harris said there are ways that designers of ASR tools could work toward being more inclusive of minority dialects, but cultural challenges could arise.

“It could be difficult to collect more minority speech data, and you have to consider consent with that,” she said. “Developers need to be more community-engaged to think about the implications of their models and whether it’s something the community would find helpful.”

Nathan Deen

Communications Officer

School of Interactive Computing

Georgia Tech HPC Community Shines at Supercomputing Conference

Nov 18, 2024 —

We’ve all heard that a single smartphone has more computing power than all the computers that NASA needed to land on the moon in 1969.

Despite the exponential growth in computing power over the past half-century, many of today’s data challenges are too complex for a single computer to handle efficiently.

Enter high-performance computing (HPC).

HPC technologies allow the workload of a single computational task—like making sense of a decade’s worth of satellite climate data or creating complex aerodynamic simulations—to be shared across multiple computing devices working as one.

Georgia Tech HPC experts are meeting with their global counterparts this week at the International Conference on High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage, and Analysis, widely known as Supercomputing (SC).

SC24 convened yesterday at the Georgia World Congress Center in downtown Atlanta. The annual event brings together scientists, engineers, researchers, and leaders from academia and industry to:

- Share best practices

- Discover new ideas

- Discuss emerging challenges

- Develop relationships

Although Georgia Tech is not formally hosting SC24, it plays a central role in the weeklong conference.

Along with the technical program, Georgia Tech has a big footprint on the SC24 exhibition floor. Shimon, the Institute’s improvisational marimba-playing robot, will greet conference attendees visiting Georgia Tech’s booth (#4415) in the exhibition hall.

“Georgia Tech has 50 researchers presenting at Supercomputing this year, reflecting our long-time commitment to leadership in high-performance computing,” said Vivek Sarkar, John P. Imlay Jr. Dean of Computing.

“I am delighted to welcome HPC researchers from around the globe to Atlanta, and I look forward to our interactions at the conference,” said Sarkar.

The dean and College of Computing researchers lead Georgia Tech’s SC24 contingent.

Sarkar will present three workshops and a paper at the conference. Faculty, research scientists, and graduate students from the School of Computational Science and Engineering (CSE) and the School of Computer Science are part of the more than 27 Georgia Tech research teams contributing to the SC24 technical program.

[RELATED: Explore the College of Computing’s latest HPC headlines]

Tech’s contingent at SC24 includes a School of CSE team that will present its new HPC algorithm on Wednesday. The algorithm is faster than existing methods, highly accurate, and empowers scalable simulations of chemical systems. The team expects it to have applications in physics, chemistry, materials science, and other fields.

The SC24 technical program also features Georgia Tech researchers from:

- The Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering

- The School of Chemistry & Biochemistry

- The School of Civil & Environmental Engineering

- The School of Electrical and Computer Engineering

- The School of Public Policy

- The Partnership for an Advanced Computing Environment (PACE)

The College of Computing has created a new website chronicling Georgia Tech’s presence at SC24.

The site features links to presentation and workshop schedules and the full SC24 agenda. It gives users an in-depth look at Georgia Tech’s latest HPC research, a guide to the hottest topics, and an interactive exploration of Tech’s HPC researchers and collaborators.

Along with the technical program, Georgia Tech has a big footprint on the SC24 exhibition floor.

Shimon, the Institute’s famed improvisational marimba-playing robot, will greet conference attendees visiting Georgia Tech’s booth (#4415) in the exhibition hall. Tech’s presenters and faculty will also spend time in the booth to meet attendees interested in learning more about the Institute’s latest HPC initiatives and achievements.

This year’s conference marks the first time that the City of Atlanta has hosted Supercomputing. SC is the leading global conference showcasing the latest HPC technologies and applications.

Ben Snedeker, Communications Manager

Georgia Tech College of Computing

albert.snedeker@cc.gatech.edu

A New Carbon-Negative Method to Produce Essential Amino Acids

Nov 21, 2024 —

Glycine, one of the critical amino acids that the system coverts carbon dioxide into. (Image Credit: NASA)

Amino acids are essential for nearly every process in the human body. Often referred to as ‘the building blocks of life,’ they are also critical for commercial use in products ranging from pharmaceuticals and dietary supplements, to cosmetics, animal feed, and industrial chemicals.

And while our bodies naturally make amino acids, manufacturing them for commercial use can be costly — and that process often emits greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide (CO2).

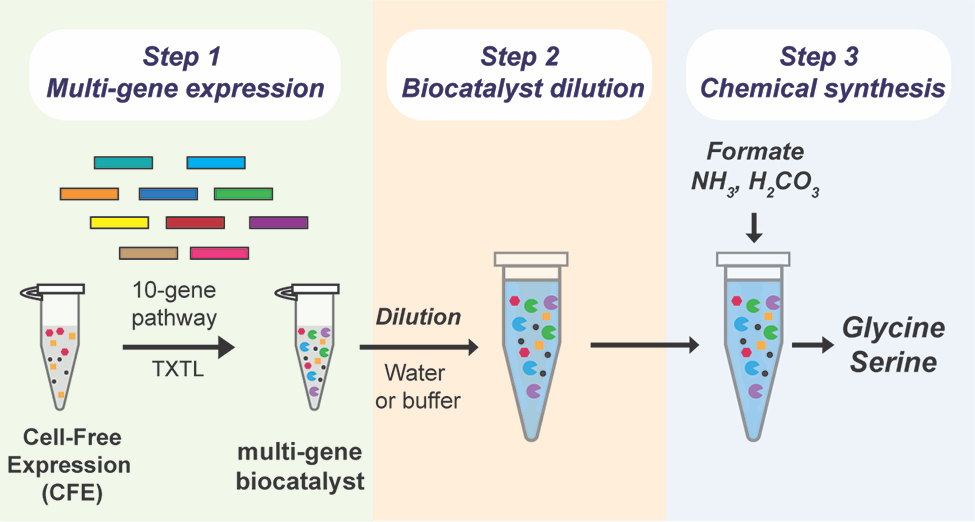

In a landmark study, a team of researchers has created a first-of-its kind methodology for synthesizing amino acids that uses more carbon than it emits. The research also makes strides toward making the system cost-effective and scalable for commercial use.

“To our knowledge, it’s the first time anyone has synthesized amino acids in a carbon-negative way using this type of biocatalyst,” says lead corresponding author Pamela Peralta-Yahya, who emphasizes that the system provides a win-win for industry and environment. “Carbon dioxide is readily available, so it is a low-cost feedstock — and the system has the added bonus of removing a powerful greenhouse gas from the atmosphere, making the synthesis of amino acids environmentally friendly, too.”

The study, “Carbon Negative Synthesis of Amino Acids Using a Cell-Free-Based Biocatalyst,” published today in ACS Synthetic Biology, is publicly available. The research was led by Georgia Tech in collaboration with the University of Washington, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, and the University of Minnesota.

The Georgia Tech research contingent includes Peralta-Yahya, a professor with joint appointments in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry and School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (ChBE); first author Shaafique Chowdhury, a Ph.D. student in ChBE; Ray Westenberg, a Ph.D student in Bioengineering; and Georgia Tech alum Kimberly Wennerholm (B.S. ChBE ’23).

Costly chemicals

There are two key challenges to synthesizing amino acids on a large scale: the cost of materials, and the speed at which the system can generate amino acids.

While many living systems like cyanobacteria can synthesize amino acids from CO2, the rate at which they do it is too slow to be harnessed for industrial applications, and these systems can only synthesize a limited number of chemicals.

Currently, most commercial amino acids are made using bioengineered microbes. “These specially designed organisms convert sugar or plant biomass into fuel and chemicals,” explains first author Chowdhury, “but valuable food resources are consumed if sugar is used as the feedstock — and pre-processing plant biomass is costly.” These processes also release CO2 as a byproduct.

Chowdhury says the team was curious “if we could develop a commercially viable system that could use carbon dioxide as a feedstock. We wanted to build a system that could quickly and efficiently convert CO2 into critical amino acids, like glycine and serine.”

The team was particularly interested in what could be accomplished by a ‘cell-free’ system that leveraged some process of a cellular system — but didn’t actually involve living cells, Peralta-Yahya says, adding that systems using living cells need to use part of their CO2 to fuel their own metabolic processes, including cell growth, and have not yet produced sufficient quantities of amino acids.

“Part of what makes a cell-free system so efficient,” Westenberg explains, “is that it can use cellular enzymes without needing the cells themselves. By generating the enzymes and combining them in the lab, the system can directly convert carbon dioxide into the desired chemicals. Because there are no cells involved, it doesn’t need to use the carbon to support cell growth — which vastly increases the amount of amino acids the system can produce.”

A novel solution

While scientists have used cell-free systems before, one of the necessary chemicals, the cell lysate biocatalyst, is extremely costly. For a cell-free system to be economically viable at scale, the team needed to limit the amount of cell lysate the system needed.

After creating the ten enzymes necessary for the reaction, the team attempted to dilute the biocatalyst using a technique called ‘volumetric expansion.’ “We found that the biocatalyst we used was active even after being diluted 200-fold,” Peralta-Yahya explains. “This allows us to use significantly less of this high-cost material — while simultaneously increasing feedstock loading and amino acid output.”

It’s a novel application of a cell-free system, and one with the potential to transform both how amino acids are produced, and the industry’s impact on our changing climate.

“This research provides a pathway for making this method cost-effective and scalable,” Peralta-Yahya says. “This system might one day be used to make chemicals ranging from aromatics and terpenes, to alcohols and polymers, and all in a way that not only reduces our carbon footprint, but improves it.”

Funding: Advanced Research Project Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program.

DOI: 10.1021/acssynbio.4c00359

Professor Pamela Peralta-Yahya, lead corresponding author of the study.

Ph.D. Student Shaafique Chowdhury, first author of the study.

Ph.D. Student Ray Westerberg

“Part of what makes a cell-free system so efficient,” Westenberg says, “is that it can use cellular enzymes without needing the cells themselves. By generating the enzymes and combining them in the lab, the system can directly convert carbon dioxide into the desired chemicals.”

Written by Selena Langner

Lab-Grown Human Immune System Model Uncovers Weakened Response in Cancer Patients

Nov 12, 2024 —

The left image shows the immune organ-on-chip, where the organoids (right) are grown to study the response of human donors. The right image shows development of types of immune cells relevant to the antibody response. (Credit: Ankur Singh)

To better understand why some cancer patients struggle to fight off infections, Georgia Tech researchers have created tiny lab-grown models of human immune systems.

These miniature models — known as human immune organoids — mimic the real-life environment where immune cells learn to recognize and attack harmful invaders and respond to vaccines. Not only are these organoids powerful new tools for studying and observing immune function in cancer, their use is likely to accelerate vaccine development, better predict disease treatment response for patients, and even speed up clinical trials.

“Our synthetic hydrogels create a breakthrough environment for human immune organoids, allowing us to model antibody production from scratch, more precisely, and for a longer duration,” said Ankur Singh, Carl Ring Family Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory.

“For the first time, we can recreate and sustain complex immunological processes in a synthetic gel, using blood, and effectively track B cell responses,” he added. “This is a gamechanger for understanding and treating immune vulnerabilities in patients with lymphoma who have undergone cancer treatment — and hopefully other disorders too.”

Led by Singh, the team created lab-grown immune systems that mimic human tonsils and lymph node tissue to study immune responses more accurately. Their research findings, published in the journal Nature Materials, mark a shift toward in vitro models that more closely represent human immunology. The team also included investigators from Emory University, Children’s Hospital of Atlanta, and Vanderbilt University.

Designing a Tiny Immune System Model

The researchers were inspired to address a critical issue in biomedical science: the poor success rate of translating preclinical findings from animal models into effective clinical outcomes, especially in the context of immunity, infection, and vaccine responses.

“While animal models are valuable for many types of research, they often fail to accurately mirror realistic human immune biology, disease mechanisms, and treatment responses,” said Monica (Zhe) Zhong, a Bioengineering Ph.D. student and the paper’s first author. “To address this, we designed a new model that faithfully replicates the unique complexity of human immune biology across molecular, cellular, tissue, and system levels.”

The team used synthetic hydrogels to recreate a microenvironment where B cells from human blood and tonsils can mature and produce antibodies. When immune cells from healthy donors or lymphoma patients are cultured in these gel-like environments, the organoids support longer cell function, allowing processes like antibody formation and adaptation to occur — similar to the human body. Utilizing the organoids for individual patients helps predict how that individual will respond to infection.

The models also enable researchers to control and test immune responses under various conditions. The team discovered that not all tissue sources are the same, and tonsil cells struggled with longevity issues. They used a specialized setup to study how healthy immune cells react to signals that help them fight infections, which failed to trigger the same response in cells from lymphoma survivors who seemingly have recovered from immunotherapy treatment.

Using organoids embedded in a novel immune organ-on-chip technology, the team observed that immune cells from lymphoma survivors treated with certain immunotherapies do not organize themselves into specific “zones,” the way they normally would in a strong immune response. This lack of organization may help explain some immune challenges cancer survivors face, as evidenced by recent clinical findings.

A Game-Changing Technology

This research is primarily of interest to infectious disease researchers, cancer researchers, immunologists, and healthcare professionals dedicated to improving patient outcomes. By studying these miniature immune systems, they can identify why current treatments may not be effective and explore new strategies to enhance immune defenses.

"Lymphoma patients treated with CD20-targeted therapies often face increased susceptibility to infections that can persist years after completing therapy.Understanding these long-term impacts on antibody responses could be key to improving both safety and quality of life for lymphoma survivors,” said Dr. Jean Koff, associate professor in the department of Hematology and Oncology at Emory University’s Winship Cancer Institute and a co-author on the paper.

“This technology provides deeper biological insights and an innovative way to monitor for recovery of immunological defects over time. It could help clinicians better identify patients who would benefit from specific interventions that reduce infection risk,” Koff added.

Another critical and promising aspect of the research is its scalability: An individual researcher can make hundreds of organoids in a single sitting. The model’s capability to target different populations — both healthy and immunosuppressed patients — vastly increases its usability for vaccine and therapeutic testing.

According to Singh, who directs the Center for Immunoengineering at Georgia Tech, the team is already pushing the research into new dimensions, including developing cellular therapies and an aged immune system model to address aging-related questions.

“At the end of the day, this work most immediately affects cancer patients and survivors, who often struggle with weakened immune responses and may not respond well to standard treatments like vaccines,” Singh explained. “This breakthrough could lead to new ways of boosting immune defenses, ultimately helping vulnerable patients stay healthier and recover more fully.”

The work was initially funded by the Wellcome Leap HOPE program. This support has led to a boost in recent funding, including a recent $7.5M grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Citation: Zhong, Z., Quiñones-Pérez, M., Dai, Z. et al. Human immune organoids to decode B cell response in healthy donors and patients with lymphoma. Nat. Mater. (2024).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-024-02037-1

Funding: Wellcome Leap HOPE Program, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, and Georgia Tech Foundation

Ankur Singh, Carl Ring Family Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory, and Monica (Zhe) Zhong, a Bioengineering Ph.D. student and the paper’s first author.

Catherine Barzler, Senior Research Writer/Editor

Institute Communications

Google Cybersecurity Team Inspired by Georgia Tech’s AIxCC Win

Nov 04, 2024 —

Members of the recently victorious cybersecurity group known as Team Atlanta received recognition from one of the top technology companies in the world for their discovery of a zero-day vulnerability in the DARPA AI Cyber Challenge (AIxCC) earlier this year.

On November 1, a team of Google’s security researchers from Project Zero announced they were inspired by the Georgia Tech students and alumni on the team that discovered a flaw in SQLite. This widely used open-source database ran the competition’s scoring algorithm.

According to a post from the project’s blog, when Google researchers saw the success of Atlantis, the large language model (LLM) used in AIxCC, they deployed their LLM to check vulnerabilities in SQLite.

Google’s Big Sleep tool discovered a security flaw in SQLite, an exploitable stack buffer underflow. Project Zero reported the vulnerability and it was patched almost immediately.

“We’re thrilled to see our work on LLM-based bug discovery and remediation inspiring further advancements in security research at Google,” said Hanqing Zhao, a Georgia Tech Ph.D. student. “It’s incredibly rewarding to witness the broader community recognizing and citing our contributions to AI and LLM-driven security efforts.”

Zhao led a group within Team Atlanta focused on tracking their project’s success during the competition, leading to the bug's discovery. He also wrote a technical breakdown of their findings in a blog post cited by Google’s Project Zero.

“This achievement was entirely autonomous, without any human intervention, and we hadn’t even anticipated targeting SQLite3,” he said. “The outcome highlighted the transformative potential of generative AI in security research. Our approach is rooted in a simple yet effective philosophy: mimic the expertise of seasoned security researchers using LLMs.”

The DARPA AI Cyber Challenge (AIxCC) semi-final competition was held at DEF CON 32 in Las Vegas. Team Atlanta, which included Georgia Tech experts, was among the contest’s winners.

Team Atlanta will now compete against six other teams in the final round, which will take place at DEF CON 33 in August 2025. The finalists will use the $2 million semi-final prize to improve their AI system over the next 12 months. Team Atlanta consists of past and present Georgia Tech students and was put together with the help of SCP Professor Taesoo Kim.

The AI systems in the finals must be open-sourced and ready for immediate, real-world launch. The AIxCC final competition will award the champion a $4 million grand prize.

The team tested their cyber reasoning system (CRS), dubbed Atlantis, on software used for data management, website support, healthcare systems, supply chains, electrical grids, transportation, and other critical infrastructures.

Atlantis is a next-generation, bug-finding and fixing system that can hunt bugs in multiple coding languages. The system immediately issues accurate software patches without any human intervention.

AIxCC is a Pentagon-backed initiative announced in August 2023 and will award up to $20 million in prize money throughout the competition. Team Atlanta was among the 42 teams that qualified for the semi-final competition earlier this year.

John Popham

Communications Officer II | School of Cybersecurity and Privacy

No Matter the Task, This New Exoskeleton AI Controller Can Handle It

Nov 13, 2024 —

A new exoskeleton controller developed by Georgia Tech engineers works for dozens of dozens of realistic human lower limb movements, including dynamic actions like tug-of-war and jumping, as well as more typical unstructured movements like starting and stopping, twisting, and meandering. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

A leap forward in artificial intelligence control from Georgia Tech engineers could one day make robotic assistance for everyday activities as easy as putting on a pair of pants.

Researchers have developed a task-agnostic controller for robotic exoskeletons that’s capable of assisting users with all kinds of leg movements, including ones the AI has never seen before.

It’s the first controller able to support a dozens of realistic human lower limb movements, including dynamic actions like lunging and jumping, as well as more typical unstructured movements like starting and stopping, twisting, and meandering.

Paired with a slimmed down exoskeleton integrated into a pair of athletic pants that was designed by X, “The Moonshot Factory,” the system requires no calibration or training. Users can put on the device, activate the controller, and go.

The study was led by researchers in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering (ME) and the Georgia Tech Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Machines.

Their system takes a first big step toward devices that could help people navigate the real world, not just the controlled environment of a lab. That could mean helping airline baggage handlers move hundreds of suitcases or factory workers with heavy, labor-intensive tasks. It could also mean improving mobility for older adults or stroke patients who can’t get around as well as they used to.

“The idea is to provide real human augmentation across the high diversity of tasks that people do in their everyday lives, and that could be for clinical applications, industrial applications, recreation, or the military,” said Aaron Young, ME associate professor and the senior researcher on a study describing the controller published Nov. 13 in the journal Nature.

Joshua Stewart

College of Engineering

Bridging Tradition and Technology: Robotics and AI Open a New Path for Classical Indian Music

Nov 13, 2024 — Atlanta

Ph.D. student Raghav Sankaranarayanan with Hathaani, his violin-playing robot. (Credit: Wes McRae)

Raghavasimhan Sankaranarayanan has over 200 album and film soundtrack credits to his name, and he has performed in more than 2,000 concerts across the globe. He has composed music across many genres and received numerous awards for his technical artistry on the violin.

He is also a student at Georgia Tech, finishing up his Ph.D. in machine learning and robotics.

One might wonder why a successful professional musician would choose to become a student again.

“I always wanted to integrate technology, music, and robotics because I love computers and machines that can move,” he said. “There’s been little research on Indian music from a technological perspective, and the AI and music industries largely focus on Western music. This bias is something I wanted to address.”

Sankaranarayanan, who began playing the violin at age 4, has focused his academic studies on bridging the musically technical with the deeply technological. Over the past six years at Georgia Tech, he has explored robotic musicianship, creating a robot violinist and an accompanying synthesizer capable of understanding, playing, and improvising the music closest to his heart: classical South Indian music.

The Essence of Carnatic Music

Carnatic music, a classical form of South Indian music, is believed to have originated in the Vedas, or ancient sacred Hindu texts. The genre has remained faithful to its historic form, with performers often using non-amplified sound or only a single mic. A typical performance includes improvisations and musical interaction between musicians in which violinists play a crucial role.

Carnatic music is characterized by intricate microtonal pitch variations known as gamakas — musical embellishments that modify a single note’s pitch or seamlessly transition between notes. In contrast, Western music typically treats successive notes as distinct entities.

Out of a desire to contribute technological advancements to the genre, Sankaranarayanan set out to innovate. When he joined the Center for Music Technology program under Gil Weinberg, professor and the Center’s director, no one at Georgia Tech had ever attempted to create a string-based robot.

“In our work, we develop physical robots that can understand music, apply logic to it, and then play, improvise, and inspire humans,” said Weinberg. “The goal is to foster meaningful interactions between robots and human musicians that foster creativity and the kind of musical discoveries that may not have happened otherwise.”

The Brain and the Body

Sankaranarayanan conceptualizes the robot as comprising two parts: the brain and the body. The “body” consists of mechanical systems that require algorithms to move accurately, including sliders and actuators that convert electric signals into motion to produce the sound of music. The “brain” consists of algorithms that enable the robot to understand and generate music.

In robotic musicianship, algorithms interpret and perform music, but building these algorithms for non-Western music is challenging; far less data is available for these forms. This lack of representation limits the capabilities of robotic musicianship and diminishes the cultural richness diverse musical forms can offer.

Classical algorithms would struggle to capture the nuances of Carnatic music. To address this, Sankaranarayanan collected data specifically to model gamakas in Carnatic music. Then, using audio from performances by human musicians, he developed a machine-learning model to learn those gamakas.

“You may ask, ‘Why not just use a computer?’ A computer can respond with algorithms, but music’s physicality is vital,” Weinberg said. “When musicians collaborate, they rely on the visual cues of movement, which make the interaction feel alive. Moreover, acoustic sound created by a physical instrument is richer and more expressive than computer-generated sound, and a robot musician provides this.”

Sankaranarayanan built the robot incrementally. Initially, he developed a bow mechanism that moved across wheels; now, the robot violin uses a real bow for authentic sound production.

Developing a New Musical Language

Another challenge involves technologies like MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface), a protocol that enables electronic musical instruments and devices to communicate and sync by sending digital information about musical notes and performances. MIDI, however, is based on Western music systems and is limited in its application to music with microtonal pitch variations such as Carnatic music.

So Sankaranarayanan and Weinberg developed their own system. Using audio files of human violin performances, the system extracts musical features that inform the robot on bowing techniques, left-hand movements, and pressure on strings. The software synthesizer then listens to Sankaranarayanan’s playing, responding and improvising in real time and creating a dynamic interplay between human and robot.

“Like in many other fields, bias also exists in the area of music AI, with many researchers and companies focusing on Western music and using AI to understand tonal systems,” Weinberg said. “Raghav’s work aims to showcase how AI can also generate and understand non-Western music, which he has achieved beautifully.”

Giving Back to the Community

Carnatic music and its community of musicians shaped Sankaranarayanan's musical sensibility, motivating him to give back. He is developing an app to teach Carnatic music to help make the genre more appealing to younger audiences.

“By merging tradition with technology, we can expand the reach of traditional Carnatic music to younger musicians and listeners who desire more technological engagement,” Sankaranarayanan said.

Through his innovative work, he is not just preserving Carnatic music but also reshaping its future for a digital age, inviting a new generation to engage with its deep heritage.

Catherine Barzler, Senior Research Writer/Editor