Lab-Grown Human Immune System Model Uncovers Weakened Response in Cancer Patients

Nov 12, 2024 —

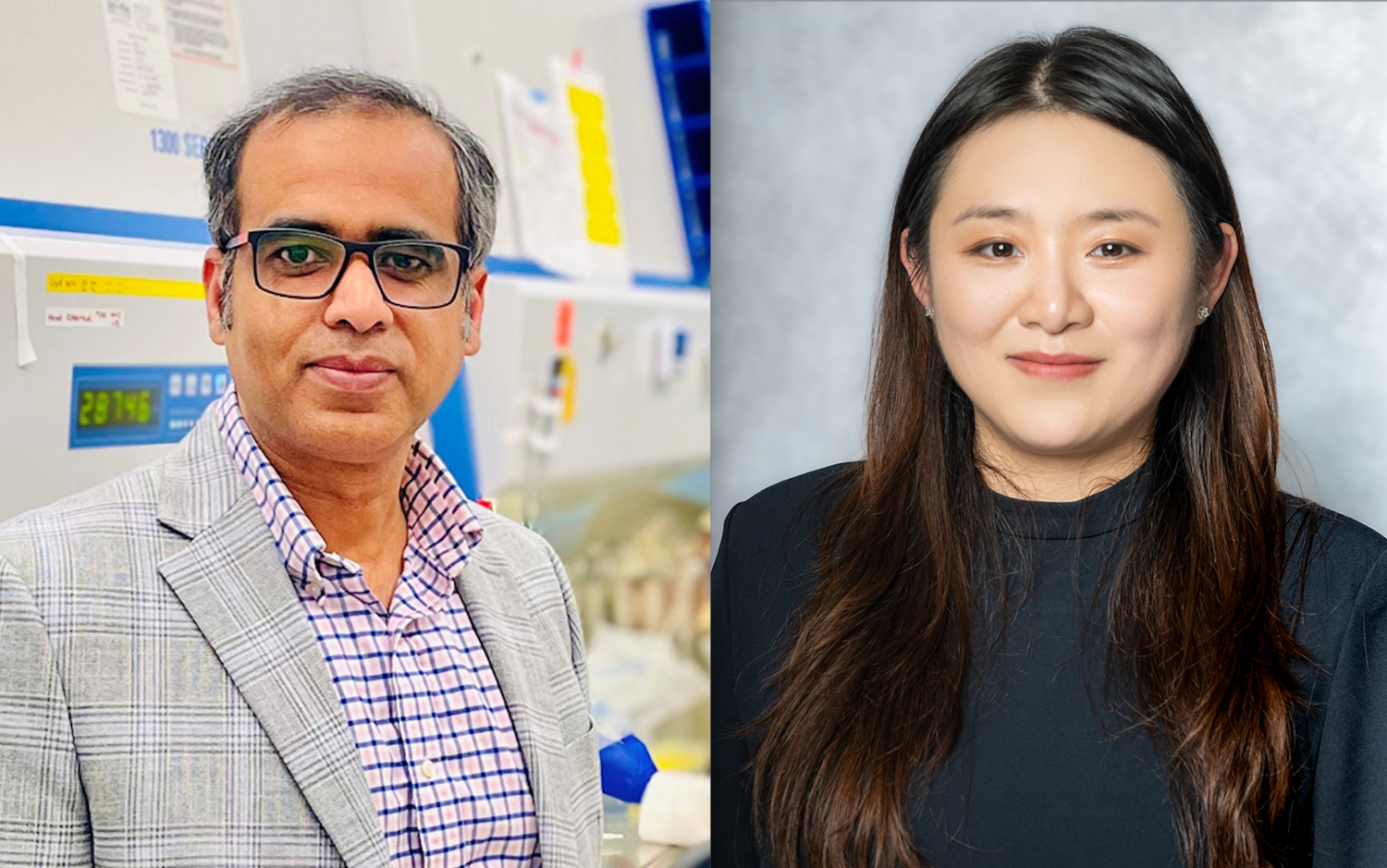

The left image shows the immune organ-on-chip, where the organoids (right) are grown to study the response of human donors. The right image shows development of types of immune cells relevant to the antibody response. (Credit: Ankur Singh)

To better understand why some cancer patients struggle to fight off infections, Georgia Tech researchers have created tiny lab-grown models of human immune systems.

These miniature models — known as human immune organoids — mimic the real-life environment where immune cells learn to recognize and attack harmful invaders and respond to vaccines. Not only are these organoids powerful new tools for studying and observing immune function in cancer, their use is likely to accelerate vaccine development, better predict disease treatment response for patients, and even speed up clinical trials.

“Our synthetic hydrogels create a breakthrough environment for human immune organoids, allowing us to model antibody production from scratch, more precisely, and for a longer duration,” said Ankur Singh, Carl Ring Family Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory.

“For the first time, we can recreate and sustain complex immunological processes in a synthetic gel, using blood, and effectively track B cell responses,” he added. “This is a game changer for understanding and treating immune vulnerabilities in patients with lymphoma who have undergone cancer treatment — and hopefully other disorders too.”

Led by Singh, the team created lab-grown immune systems that mimic human tonsils and lymph node tissue to study immune responses more accurately. Their research findings, published in the journal Nature Materials, mark a shift toward in vitro models that more closely represent human immunology. The team also included investigators from Emory University, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, and Vanderbilt University.

Designing a Tiny Immune System Model

The researchers were inspired to address a critical issue in biomedical science: the poor success rate of translating preclinical findings from animal models into effective clinical outcomes, especially in the context of immunity, infection, and vaccine responses.

“While animal models are valuable for many types of research, they often fail to accurately mirror realistic human immune biology, disease mechanisms, and treatment responses,” said Monica (Zhe) Zhong, a bioengineering Ph.D. student and the paper’s first author. “To address this, we designed a new model that faithfully replicates the unique complexity of human immune biology across molecular, cellular, tissue, and system levels.”

The team used synthetic hydrogels to recreate a microenvironment where B cells from human blood and tonsils can mature and produce antibodies. When immune cells from healthy donors or lymphoma patients are cultured in these gel-like environments, the organoids support longer cell function, allowing processes like antibody formation and adaptation to occur — similar to the human body. Utilizing the organoids for individual patients helps predict how that individual will respond to infection.

The models also enable researchers to control and test immune responses under various conditions. The team discovered that not all tissue sources are the same, and tonsil cells struggled with longevity issues. They used a specialized setup to study how healthy immune cells react to signals that help them fight infections, which failed to trigger the same response in cells from lymphoma survivors who seemingly have recovered from immunotherapy treatment.

Using organoids embedded in a novel immune organ-on-chip technology, the team observed that immune cells from lymphoma survivors treated with certain immunotherapies do not organize themselves into specific “zones,” the way they normally would in a strong immune response. This lack of organization may help explain some immune challenges cancer survivors face, as evidenced by recent clinical findings.

A Game-Changing Technology

This research is primarily of interest to infectious disease researchers, cancer researchers, immunologists, and healthcare professionals dedicated to improving patient outcomes. By studying these miniature immune systems, they can identify why current treatments may not be effective and explore new strategies to enhance immune defenses.

"Lymphoma patients treated with CD20-targeted therapies often face increased susceptibility to infections that can persist years after completing therapy. Understanding these long-term impacts on antibody responses could be key to improving both safety and quality of life for lymphoma survivors,” said Dr. Jean Koff, associate professor in the department of Hematology and Oncology at Emory University’s Winship Cancer Institute and a co-author on the paper.

“This technology provides deeper biological insights and an innovative way to monitor for recovery of immunological defects over time. It could help clinicians better identify patients who would benefit from specific interventions that reduce infection risk,” Koff added.

Another critical and promising aspect of the research is its scalability: An individual researcher can make hundreds of organoids in a single sitting. The model’s capability to target different populations — both healthy and immunosuppressed patients — vastly increases its usability for vaccine and therapeutic testing.

According to Singh, who directs the Center for Immunoengineering at Georgia Tech, the team is already pushing the research into new dimensions, including developing cellular therapies and an aged immune system model to address aging-related questions.

“At the end of the day, this work most immediately affects cancer patients and survivors, who often struggle with weakened immune responses and may not respond well to standard treatments like vaccines,” Singh explained. “This breakthrough could lead to new ways of boosting immune defenses, ultimately helping vulnerable patients stay healthier and recover more fully.”

The work was initially funded by the Wellcome Leap HOPE program. This support has led to a boost in recent funding, including a recent $7.5 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Citation: Zhong, Z., Quiñones-Pérez, M., Dai, Z. et al. Human immune organoids to decode B cell response in healthy donors and patients with lymphoma. Nat. Mater. (2024).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-024-02037-1

Funding: Wellcome Leap HOPE Program, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, and Georgia Tech Foundation

Ankur Singh, Carl Ring Family Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory, and Monica (Zhe) Zhong, a Bioengineering Ph.D. student and the paper’s first author.

Catherine Barzler, Senior Research Writer/Editor

Institute Communications

catherine.barzler@gatech.edu

Future of AI and Policy Among Key Topics at Inaugural School of Interactive Computing Summit

Nov 12, 2024 — Atlanta

School of IC's Josiah Hester (left) and Cindy Lin discuss AI's future impact on sustainability. Photo by Terence Rushin/College of Computing.

This month, the future of artificial intelligence (AI) was spotlighted as more than 120 academic and industry researchers participated in the Georgia Tech School of Interactive Computing’s inaugural Summit on Responsible Computing, AI, and Society.

With looming questions about AI's growing roles and consequences in nearly every facet of modern life, School of IC organizers felt the time was right to diverge from traditional conferences that focus on past work and published research.

“Presenting papers is about disseminating work that has already been completed. Who gets to be in the room is determined by whose paper gets accepted,” said Mark Riedl, School of IC professor.

“Instead, we wanted the summit talks to speculate on future directions and what challenges we as a community should be thinking about going forward.”

The two-day summit, held at Tech’s Global Learning Center Oct. 28-30, convened to discuss consequential questions like:

- Is society ready to accept more responsibility as greater advancements in technologies like AI are made?

- Should society stop to think about potential consequences before these advancements are implemented on its behalf, and what could those consequences be?

- What policies should be enacted for these technologies to mitigate harms and augment societal benefits?

A highlight of the summit’s opening day was Meredith Ringel Morris's keynote address. As director of human-AI interaction research at Google DeepMind, she presented a possible future in which humans could use AI to create a digital afterlife.

In her remarks, Morris discussed AI clones, which are AI avatars of specific human beings with high autonomy and task-performing capabilities. Someone could leave such an agent behind as a memory for loved ones to enjoy once they are gone, and future generations could access it to learn more about an ancestor.

On the other hand, it could easily lead to loved ones experiencing extended grief because they have trouble moving on from losing a family member.

These AI capabilities are in development and will soon be publicly available. As industry and academic researchers continue to develop them, the public needs to learn about their eminent impacts.

“There’s a lot that needs to be done in educating people,” Morris said. “It’s hard for well-intentioned and thoughtful system designers to anticipate all the harm. We must be prepared some people are going to use AI in ways we don’t anticipate, and some of those ways are going to be undesirable. What legal and education structures can we create that will help?”

In addition to Morris’s keynote, the summit’s first day included 20 talks about future and emerging technologies in AI, sustainability, healthcare, and other fields.

The second day featured eight talks on translating interventions and safeguards into policy.

Day-two speakers included:

- Orly Lobel, Warren Distinguished Professor of Law and director of the Center for Employment and Labor Policy at the University of California-San Diego. Lobel worked on President Obama’s policy team on innovation and labor market competition, and she advises the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

- Sorelle Friedler, Shibulal Family Professor of Computer Science at Haverford College. She worked in the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) under the Biden-Harris Administration and helped draft the AI Bill of Rights.

- Jake Metcalf, researcher and program director for AI on the Ground at the think tank Data & Society. The organization produces reports on data science and equity for the US Government.

- Divyansh Kaushik, Vice President of Beacon Global Strategies, has given testimony to the US Senate on AI research and development.

Kaushik earned a Ph.D. in machine learning from Carnegie Mellon University before beginning his career in policy. He highlighted the importance of policymakers fostering relationships with academic researchers.

“Policymakers think about what could go wrong,” Kaushik said. “Academia can offer evidence-based answers.”

The summit also hosted a doctoral consortium, which allowed advanced Ph.D. students to present their research to experts and receive feedback and mentoring.

“Being an interdisciplinary researcher is challenging,” said Shaowen Bardzell, School of IC chair.

“We wanted the next generation to be in the room listening to the experts share their visions and also to provide our own experiences when possible on how to navigate the challenges and rewards of doing work in the intersection of AI, healthcare, sustainability, and policy.”

Nathan Deen

Georgia Tech School of Interactive Computing

Communications Officer

nathan.deen@cc.gatech.edu

Digital Twins Make CO₂ Storage Safer

Nov 11, 2024 — Atlanta, GA

As greenhouse gases accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere, scientists are developing technologies to pull billions of tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air and inject it deep underground.

The idea isn’t new. In the 1970s, Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti suggested that the carbon dioxide polluting the air and warming the planet could be stored underground. The reality of how to do it cost-effectively and safely has challenged scientists for decades.

Geologic carbon storage — the subterranean storage of CO2 — comes with significant challenges, most importantly, how to avoid fracturing underground rock layers and letting gas escape into the atmosphere. Carbon, a gas, can behave erratically or leak whenever it’s stored in a compressed space, making areas geologically unstable and potentially causing legal headaches for corporations that invest in it. This uncertainty, coupled with the expense of the carbon capture process and its infrastructure, means the industry needs reliable predictions to justify it.

Georgia Tech researcher and Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar Felix J. Herrmann has an answer. His lab, Seismic Laboratory for Imaging and Modeling (SLIM), uses advanced artificial intelligence (AI) techniques to create algorithms that monitor and optimize carbon storage. The algorithms work as “digital twins,” or digital replicas of underground systems, facilitating the safe, efficient storage of CO2 underground.

“The trick is you want the carbon to stay put — to avoid the risk of, say, triggering an earthquake or the carbon leaking out,” said Herrmann, professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “We’re developing a digital twin that allows us to monitor and control what is happening underground.”

Predicting the Best Place

Waveform Variational Inference via Subsurface Extensions with Refinements (WISER) is an algorithm that uses sound waves to analyze underground structures. WISER runs on AI, enabling it to work more efficiently than most algorithms while remaining computationally feasible. To improve accuracy, WISER makes small adjustments using sound wave physics to show how fast sound travels through different materials and where there’s variation in underground layers. This helps to create detailed, reliable images of underground areas for better predictions of carbon storage.

WISER allows researchers to work with uncertainties, which is vital for understanding the risk of these underground storage projects.

Scaling the Algorithm

While Herrmann’s lab has been working to apply neural networks to seismic imaging for years now, WISER required them to increase the networks’ scale. Making multiple predictions is a much larger problem that requires a bigger, more potent network, but these types of neural networks only run on graphics processing units (GPUs), which are known for speed but are limited in memory.

To optimize the GPU, Rafael Orozco, a computational science and engineering Ph.D. student, created a new type of neural network that can train with very little memory. This open-source package, InvertibleNetworks, enables the network to train on very large inputs and create multiple output images conditioned on the observed seismic data.

WISER’s fundamental innovation is for the lab’s next concept: creating digital twins for carbon storage. These twins can act as monitoring systems to optimize and mitigate risks of carbon storage projects.

Devising the Digital Twin

Digital twins are dynamic virtual models of objects in the real world, capable of replicating their behavior and performance. They rely on real-time data to evolve and have been used to replicate factories, cities, spacecraft, and bodies, to make informed decisions about healthcare, maintenance, production, supply chains, and — in Herrmann’s case — geologic carbon storage.

Herrmann and his team have developed an “uncertainty-aware” digital twin. That means the tool can manage risks and make decisions in an uncertain, unseen environment — because it’s been designed to recognize, quantify, and incorporate uncertainties in CO2 storage.

Probing the Unseen

Subsurface conditions are diverse and complex, making the management of greenhouse gas storage a delicate process. Without careful monitoring, the injection of CO2 can increase pressure in rock formations, potentially fracturing the cap rock that is supposed to keep the gas underground.

“The digital twin addresses this through simulations in tandem with observations,” said Herrmann, whose team linked two different scientific fields — geophysics and reservoir engineering — for a more comprehensive understanding of the subsurface environment. Specifically, they combined geophysical well observations with seismic imaging.

Geophysical well observation involves drilling a hole in the subsurface in a geological area of interest and collecting data by lowering a probe into the borehole to take measurements. Seismic imaging, on the other hand, uses acoustic waves to create images based on the analysis of wave vibrations.

“Bridging the gap between different fields of research and combining various data sources allows our digital twin to provide a more accurate and detailed picture of what’s happening underground,” Herrmann said.

To integrate and leverage these diverse datasets built from observations and simulations, the team used advanced AI techniques like simulation-based inference and sequential Bayesian inference, a method of updating information as more data becomes available. The ongoing learning allows researchers to quantify uncertainties in the subsurface environment and predict how that system will respond to CO2 injection. The digital twin updates its understanding as new data becomes available.

Making Informed Decisions

Herrmann’s team tested the digital twin, simulating different states of an underground reservoir, including permeability, which is the measure of how easily fluids flow through rock. The goal was to find the maximum injection rate of CO2 without causing fractures in the cap rock.

“The work highlights how dynamic digital twins can play a key role in mitigating the risks associated with geologic carbon storage,” said Herrmann, whose research group is supported in part by large oil and gas companies, including Chevron and ExxonMobil. “Companies are now in the process of starting large offshore projects for which the digital twin is being developed.”

But there is still plenty of work to be done, he added. For instance, the digital twin can monitor the subsurface and provide critical information about that uncertain environment. It can inform. But it still needs adjustments by humans for each new CO2 injection site, and Herrmann and his team are working on further developing the technology — giving the digital twins the ability to quickly replicate themselves so they can be deployed massively and quickly to meet the demands of mitigating climate change.

“Our aim is to make them smarter,” Herrmann said. “To make them more adaptable, so they can control CO2 injections, become more responsive to risks, and adapt to a wide range of complex situations in real time.”

Writers: Jerry Grillo and Tess Malone

Media Contact: Tess Malone | tess.malone@gatech.edu

New HPC Algorithm Energizes Faster, Scalable Simulations of Chemical Systems

Nov 11, 2024 —

A first-of-its-kind algorithm developed at Georgia Tech is helping scientists study interactions between electrons. This innovation in modeling technology can lead to discoveries in physics, chemistry, materials science, and other fields.

The new algorithm is faster than existing methods while remaining highly accurate. The solver surpasses the limits of current models by demonstrating scalability across chemical system sizes ranging from large to small.

Computer scientists and engineers benefit from the algorithm’s ability to balance processor loads. This work allows researchers to tackle larger, more complex problems without the prohibitive costs associated with previous methods.

Its ability to solve block linear systems drives the algorithm’s ingenuity. According to the researchers, their approach is the first known use of a block linear system solver to calculate electronic correlation energy.

The Georgia Tech team won’t need to travel far to share their findings with the broader high-performance computing community. They will present their work in Atlanta at the 2024 International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis (SC24).

“The combination of solving large problems with high accuracy can enable density functional theory simulation to tackle new problems in science and engineering,” said Edmond Chow, professor and associate chair of Georgia Tech’s School of Computational Science and Engineering (CSE).

Density functional theory (DFT) is a modeling method for studying electronic structure in many-body systems, such as atoms and molecules.

An important concept DFT models is electronic correlation, the interaction between electrons in a quantum system. Electron correlation energy is the measure of how much the movement of one electron is influenced by presence of all other electrons.

Random phase approximation (RPA) is used to calculate electron correlation energy. While RPA is very accurate, it becomes computationally more expensive as the size of the system being calculated increases.

Georgia Tech’s algorithm enhances electronic correlation energy computations within the RPA framework. The approach circumvents inefficiencies and achieves faster solution times, even for small-scale chemical systems.

The group integrated the algorithm into existing work on SPARC, a real-space electronic structure software package for accurate, efficient, and scalable solutions of DFT equations. School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Professor Phanish Suryanarayana is SPARC’s lead researcher.

The group tested the algorithm on small chemical systems of silicon crystals numbering as few as eight atoms. The method achieved faster calculation times and scaled to larger system sizes than direct approaches.

“This algorithm will enable SPARC to perform electronic structure calculations for realistic systems with a level of accuracy that is the gold standard in chemical and materials science research,” said Suryanarayana.

RPA is expensive because it relies on quartic scaling. When the size of a chemical system is doubled, the computational cost increases by a factor of 16.

Instead, Georgia Tech’s algorithm scales cubically by solving block linear systems. This capability makes it feasible to solve larger problems at less expense.

Solving block linear systems presents a challenging trade-off in solving different block sizes. While larger blocks help reduce the number of steps of the solver, using them demands higher computational cost per step on computer processors.

Tech’s solution is a dynamic block size selection solver. The solver allows each processor to independently select block sizes to calculate. This solution further assists in scaling, and improves processor load balancing and parallel efficiency.

“The new algorithm has many forms of parallelism, making it suitable for immense numbers of processors,” Chow said. “The algorithm works in a real-space, finite-difference DFT code. Such a code can scale efficiently on the largest supercomputers.”

Georgia Tech alumni Shikhar Shah (Ph.D. CSE 2024), Hua Huang (Ph.D. CSE 2024), and Ph.D. student Boqin Zhang led the algorithm’s development. The project was the culmination of work for Shah and Huang, who completed their degrees this summer. John E. Pask, a physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, joined the Tech researchers on the work.

Shah, Huang, Zhang, Suryanarayana, and Chow are among more than 50 students, faculty, research scientists, and alumni affiliated with Georgia Tech who are scheduled to give more than 30 presentations at SC24. The experts will present their research through papers, posters, panels, and workshops.

SC24 takes place Nov. 17-22 at the Georgia World Congress Center in Atlanta.

“The project’s success came from combining expertise from people with diverse backgrounds ranging from numerical methods to chemistry and materials science to high-performance computing,” Chow said.

“We could not have achieved this as individual teams working alone.”

Bryant Wine, Communications Officer

bryant.wine@cc.gatech.edu

AI Model Creates Invisible Digital Masks to Defend Against Unwanted Facial Recognition

Nov 07, 2024 —

Just as a chameleon changes colors to mask itself from predators, new AI-powered technology is protecting people’s photos from online privacy threats.

The innovative model, developed at Georgia Tech, creates invisible digital masks for personal photos to thwart unwanted online facial recognition while preserving the image quality.

Anyone who posts photos of themselves risks having their privacy violated by unauthorized facial image collection. Online criminals and other bad actors collect facial images by web scraping to create databases.

These illicit databases enable criminals to commit identity fraud, stalking, and other crimes. The practice also opens victims to unwanted targeted ads and attacks.

The new model is called Chameleon. Unlike current models, which produce different masks for each user’s photos, Chameleon creates a single, personalized privacy protection (P-3) mask for all of a user’s facial photos.

A bespoke P-3 mask is created based on a few user-submitted facial photos. After applying the mask, protected photos won’t be detectable by someone scanning for the user’s face. Instead, the unwanted scan will identify the protected photos as being someone else.

The Chameleon model was developed by Professor Ling Liu of the School of Computer Science (SCS), Ph.D. students Sihao Hu and Tiansheng Huang, and Ka-Ho Chow, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong and Liu’s former Ph.D. student.

During development, the team accomplished its two main goals: protecting the person's identity in the photo and ensuring a minimal visual difference between the original and masked photos.

The researchers said a notable visual difference often exists between the original and photos using current masking models. However, Chameleon preserves much of the original photo’s quality among various facial images.

In several research tests, Chameleon outperformed three top facial recognition protection models in visual and protective metrics. The tests also showed that Chameleon offers more substantial privacy protection while being faster and more resource-efficient.

In the future, Huang said they would like to apply Chameleon’s methods to other uses.

“We would like to use these techniques to protect images from being used to train artificial intelligence generative models. We could protect the image information from being used without consent,” he said.

The research team aims to release Chameleon code publicly on GitHub to allow others to improve their work.

“Privacy-preserving data sharing and analytics like Chameleon will help to advance governance and responsible adoption of AI technology and stimulate responsible science and innovation,” said Liu.

The paper on Chameleon, Personalized Privacy Protection Mask Against Unauthorized Facial Recognition, was presented earlier this month at ECCV 2024.

Morgan Usry, Communications Officer, School of Computer Science

Novel Machine Learning Techniques Measure Ocean Oxygen Loss More Accurately

Nov 12, 2024 —

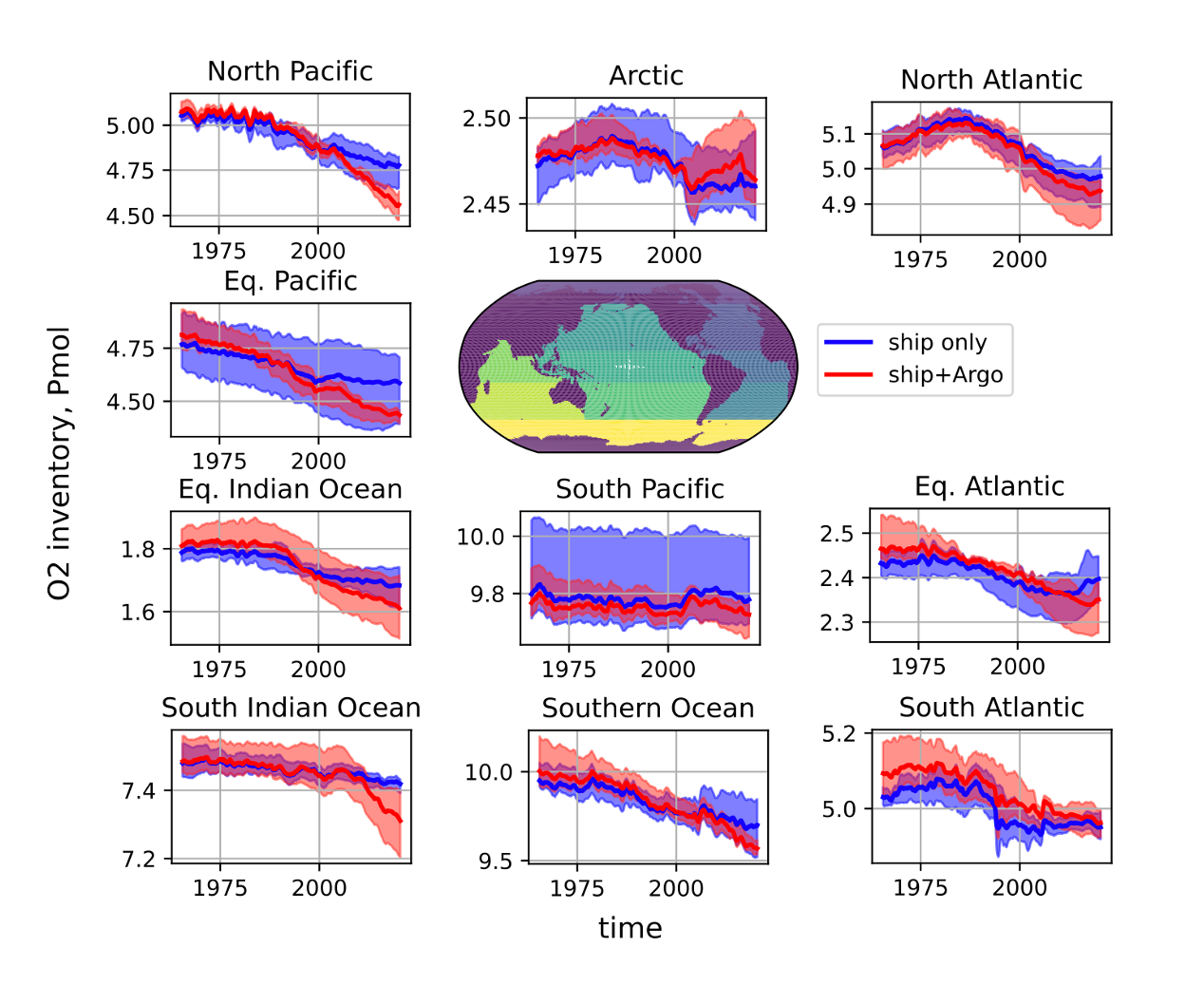

Using data from Argo floats (pictured) and historic ship measurements, Georgia Tech researchers developed new machine learning techniques to better understand global ocean oxygen loss. (Credit: Argo Program, UCSD)

Oxygen is essential for living organisms, particularly multicellular life, to metabolize organic matter and energize all life activities. About half of the oxygen we breathe comes from terrestrial plant life, such as forests and grasslands, while the other half is produced through photosynthesis by marine algae in the ocean's surface waters.

Oxygen concentrations are declining in many parts of the world’s oceans. Experts believe this drop is linked to the ocean’s surface warming and its impacts on the physics and chemistry of seawater, though the problem is not fully understood. Temperature plays a crucial role in determining how oxygen dissolves in seawater; as water warms, it loses its ability to hold gas.

“Calculating the amount of oxygen lost from the oceans is challenging due to limited historical measurements and inconsistent timing,” said Taka Ito, oceanographer and professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Georgia Tech. “To understand global oxygen levels and their changes, we need to fill in many data gaps.”

A group of student researchers sought to address this issue. Led by Ito, the team developed a new machine learning-based approach to more accurately understand and represent the decline in global ocean oxygen levels. Using datasets, the team further generated a monthly map of oxygen content visualizing the ocean’s oxygen decline over several decades. Their research was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Machine Learning and Computation.

“Marine scientists need to understand the distribution of oxygen in the ocean, how much it's changing, where the changes are occurring, and why,” said Ahron Cervania, a Ph.D. student in Ito’s lab. “Statistical methods have long been used for these estimates, but machine learning techniques can improve the accuracy and resolution of our oxygen assessments.”

The project began three years ago with support from the National Science Foundation, and the team initially focused solely on Atlantic Ocean data to test the new method. They used a computational model to generate hypothetical observations, which allowed them to assess how well they could reconstruct missing oxygen level information using only a fraction of the data combined with machine learning. After developing this method, the team expanded to global ocean observations, involving undergraduate students and delegating tasks across different ocean basins.

Under Ito’s guidance, Cervania and other student researchers developed algorithms to analyze the relationships between oxygen content and variables like temperature, salinity, and pressure. They used a dataset of historical, ship-based oxygen observations since the 1960s and recent data from Argo floats — autonomous drifting devices that collect and measure temperature and salinity. Although oxygen data existed before the 1960s, earlier records have accuracy issues, so the team focused on data from the 1960s onward. They then created a global monthly map of ocean oxygen content from 1965 to the present.

“Using a machine learning approach, we were able to assess the rate of oxygen loss more precisely across different periods and locations,” Cervania said. “Our findings indicate that incorporating float data significantly enhances the estimate of oxygen loss while also reducing uncertainty.”

The team found that the world’s oceans have lost oxygen at a rate of about 0.7% per decade from 1970 to 2010. This estimate suggests a relatively rapid ocean response to recent climate change, with potential long-term impacts on marine ecosystems’ health and sustainability. Their estimate also falls within the range of decline suggested by other studies, indicating the accuracy and efficacy of their approach.

“We calculated trends in global oxygen levels and the ocean’s inventory, essentially looking at the rate of change over the last five decades,” Cervania said. “It’s encouraging to see that our rate aligns with previous estimates from other methods, which gives us confidence. We are building a robust estimate from both our study and other studies.”

According to Ito, the team’s new approach addresses an ongoing challenge in the oceanographic community: how to effectively combine different data sources with varying accuracies and uncertainties to better understand ocean changes.

“The integration of advanced technologies like machine learning will be essential in filling data gaps and providing a clearer picture of how our oceans are responding to climate change.”

Citation: Ito, T., Cervania, A., Cross, K., Ainchwar, S., & Delawalla, S. (2024). Mapping dissolved oxygen concentrations by combining shipboard and Argo observations using machine learning algorithms. Journal of Geophysical Research: Machine Learning and Computation, 1, e2024JH000272.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JH000272

Funding: National Science Foundation

Basin-scale oxygen inventory trend with global ocean divided to 10 basins. Blue lines and shading show ensemble mean and ensemble range for ship-only reconstructions, and red lines and shading are for ship and Argo float reconstructions. The research team divided up the task by working on different basins. (Credit: Georgia Institute of Technology)

Taka Ito, oceanographer and professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences.

Ahron Cervania, a Ph.D. student in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences.

Catherine Barzler, Senior Research Writer/Editor

Institute Communications

catherine.barzler@gatech.edu

Research Team Awarded $7.3 Million for Machine Learning Assisted Development of High-Fidelity Two-Phase Models

Oct 25, 2024 —

A collaborative team from Georgia Tech, Purdue University, Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), Michigan State University (MSU), and Brown University have been awarded a combined $7.3 million from the Office of Naval Research (ONR) as part of the Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (MURI) program. MURI seeks to fund research teams with creative and diverse solutions to complex problems and is a major part of the Department of Defense’s (DoD) research portfolio.

Satish Kumar, Frank H. Neely Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, along with his collaborators, received the five-year award for their project, Machine learning Enabled Two-pHase flow metrologies, models, and Optimized DesignS (METHODS). Georgia Tech, CWRU, and Brown University will lead efforts of machine learning (ML)-assisted discovery of mechanistic two-phase models and generalized two phase flow model development. Purdue University (lead on the project) and MSU will lead efforts in performing two-phase flow experiments and generating high resolution data for the project.

Read the full story on the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering website.

Ashley Ritchie

George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering

Professor Aims to Bolster Internet Research Infrastructure

Nov 01, 2024 —

Network telescopes detect cybersecurity threats, measure internet traffic, and serve many research purposes. Despite these benefits, the use of this technology has declined in recent years.

School of Computer Science Associate Professor Alberto Dainotti, however, is revolutionizing network telescopes through a $1.2 million grant from the National Science Foundation.

Network telescopes use large sets of inactive IP addresses to observe unsolicited internet traffic, typically considered “pollution,” to reveal many internet phenomena. These observations can be used to detect denial-of-service attacks and find viruses or other malicious activity.

Network telescopes' ability to monitor this pollution also provides a way to track internet connectivity. Network telescopes are one of the tools used by IODA, a system tracking connectivity worldwide created by Dainotti’s lab.

The larger and more accurate the telescope, the more inactive IP addresses it has. Due to the increasing cost and decreasing availability of IP addresses, creating and maintaining large network telescopes has become difficult for universities. Institutions have sold many of the addresses they own or allocated them to devices using the internet.

Dainotti will use his NSF grant to help universities and other organizations again have powerful network telescopes.

“If we stop seeing pollution coming from a particular area, maybe there’s something wrong with connectivity there since that pollution is typically happening constantly,” Dainotti said.

While universities might not have large numbers of inactive IP addresses to dedicate solely to a network telescope, many addresses aren’t always in use. Until now, it has not been easy to track this activity. However, Dainotti has created a system to detect this automatically. Using this method, organizations can create what Dainotti calls a dynamic network telescope.

The dynamic network telescopes also solve another problem: some malicious actors have learned how to detect and block the sets of IP addresses used in network telescopes. Using the dynamic approach makes it harder for them to track which addresses are currently being used.

“The spirit of this proposal is to reenable organizations to have this precious research infrastructure in a different way, but with the same purpose,” Dainotti said.

Morgan Usry, Communications Officer, School of Computer Science

Georgia Tech Hosts University Leaders to Discuss Safeguarding U.S. Research

Oct 31, 2024 — Atlanta

Amid shifting geopolitics and changing national priorities, American higher-education institutions are putting a special emphasis on conducting research securely. To that end, more than 100 leaders in academia and the federal government from across the U.S. met recently to discuss how to accomplish this important task. The inaugural Research Collaboration and Safeguards Workshop, held on September 19, 2024, took place at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Georgia Tech’s outgoing Executive Vice President for Research (EVPR), Chaouki Abdallah, opened the event, noting that global relationships are evolving rapidly, “both with our adversaries and our partners.” Accordingly, to protect U.S. national and economic security, how academic research is conducted must also evolve — in conjunction with federal agencies, industry, and other academic partners.

Speakers from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Department of Defense (DoD) emphasized that these agencies want universities to have open and secure international collaborations. These partnerships are created by building trust, formalizing research security processes, and empowering research communities to make risk-informed decisions.

Sarah Stalker-Lehoux, NSF deputy chief of Research Security Strategy and Policy, described the present and future states of research security, particularly regarding international collaborations. She outlined the individual research security responsibilities for each entity involved in a partnership:

- Funders should work to mitigate risk, define their risk tolerance, and work toward saying “yes” to international research collaborations.

- Research institutions should create a culture of research security and safety across their campuses.

- Researchers should promote a culture of research security and safety, as well as communication, in their labs.

Bindu Nair, DoD director of Basic Research, highlighted the agency’s commitment to preserving open science, which includes international collaborations.

“The DoD has prioritized research security for the last 50-plus years, while maintaining high publication citations and patent counts. As research security has become a government-wide priority, the DoD has strategically led the conversation,” Nair noted. “Our participation in the Georgia Tech Research Collaboration and Safeguards Workshop was an effort to update the academic and research communities on the current rollout of new research security guidelines and policy.”

The workshop’s presenters emphasized that every person — and every entity — engaged in research is accountable for protecting U.S. interests.

After the event, Christopher King, interim vice president for Research at the University of Georgia, said that his faculty are telling him “that they want to work with mission-agency partners like the DoD, NSF, and the Department of Energy, and they want guidance on how to do this correctly and safely.”

King added, “A few schools — like Georgia Tech — are really outliers in how long they have been conducting research with federal partners that require substantial research security safeguards. A workshop like this brings institutions at every experience level into the conversation.”

To this end, Georgia Tech is actively building research partnerships with historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and minority-serving institutions (MSIs). Speakers from AAMU-RISE (Alabama A&M University in Huntsville) and Tougaloo College (Jackson, Mississippi) presented at the Research Collaborations and Safeguards Workshop.

In addition, more than 170 government, industry, national lab, and academic representatives attended a November 2023 Research Collaboration Forum, hosted by Georgia Tech’s Research Collaboration Initiative, to develop research partnerships with HBCUs.

Tim Lieuwen, Georgia Tech interim executive vice president for Research, closed the event by saying, “Research is most successful when it is collaborative. We want your research, and your research collaborations, to succeed and grow. We all have a shared responsibility to safeguard our research; to do this successfully, we must build partnerships in this arena as well. That is why all of us are here today — to move in this direction.”

The success of the initial Research Collaborations and Safeguards Workshop lays the groundwork for continued conversations in this critical area, and the Institute looks forward to welcoming these same partners — and new ones — to next year’s meeting.

Angela Ayers

Assistant Vice President of Research Communications

angela.ayers@research.gatech.edu