34th Annual Suddath Symposium

Visit Suddath Symposium website for full details and registration.

AGENDA

Wednesday, March 18: 1:00 - 5:00 p.m.

Thursday, March 19: 8:30 a.m. - 5:00 p.m.

Georgia CTSA K-Club

REGISTER HERE

A facilitated panel discussion, led by Julie Hawk, to discuss strategies for adjusting research proposal tone and language.

Panelists:

IBB Seminar

Michael A. Helmrath, MD

Surgical Director, Intestinal Rehabilitation Program

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

HYBRID EVENT

*Register here for Zoom link for virtual participation

Georgia Tech’s Soft Robotics Flips the Script on ‘The Terminator’

Oct 27, 2025 —

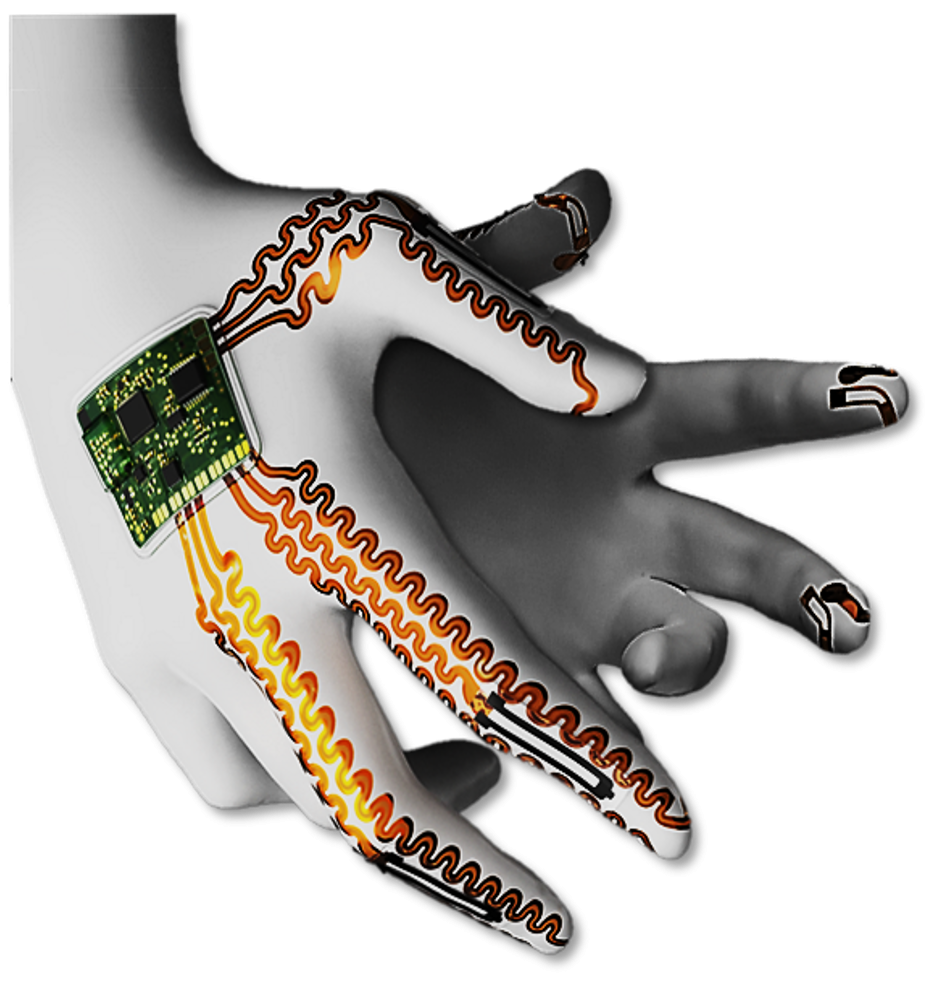

A mock-up of an AI-powered glove with muscles made from lifelike materials paired with intelligent control systems. The technology learns from the body and adapts in real time, creating motion that feels natural, responsive, and safe enough to support recovery.

Pop culture has often depicted robots as cold, metallic, and menacing, built for domination, not compassion. But at Georgia Tech, the future of robotics is softer, smarter, and designed to help.

“When people think of robots, they usually imagine something like The Terminator or RoboCop: big, rigid, and made of metal,” said Hong Yeo, the G.P. “Bud” Peterson and Valerie H. Peterson Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering. “But what we’re developing is the opposite. These artificial muscles are soft, flexible, and responsive — more like human tissue than machine.”

Yeo’s latest study, published in Materials Horizons, explores AI-powered muscles made from lifelike materials paired with intelligent control systems. The technology learns from the body and adapts in real time, creating motion that feels natural, responsive, and safe enough to support recovery.

Muscles That Think, Materials That Feel

Traditional robotics relies on steel, wires, and motors, but rarely captures the nuances of human motion. Yeo’s research takes a different approach. He uses hierarchically structured fibers, which are flexible materials built in layers, much like muscle and tendon. They can sense, adapt, and even “remember” how they’ve moved before.

Yeo trains machine learning algorithms to adjust those pliable materials in real time with the right amount of force or flexibility for each task.

“These muscles don’t only respond to commands,” Yeo said. “They learn from experience. They can adapt and self-correct, which makes motion smoother and more natural.”

The result of that research is deeply human. For someone recovering from a stroke or limb loss, each deliberate movement rebuilds not just strength — it rebuilds confidence, independence, and a sense of self.

A Glove That Gives Freedom Back

One of the first real-world applications is a prosthetic glove powered by artificial muscles (published in ACS Nano, 2025), a device that behaves more like a helping hand than a mechanical tool. Traditional prosthetics rely on rigid motors and preset motions, but Yeo’s design mirrors the natural give-and-take of real muscle.

Inside the glove, thin layers of stretchable fibers and sensors contract, twist, and flex in sync with the wearer’s intent. The glove can fine-tune grip strength, reduce tremors, and respond instantly to the user’s movements, bringing dexterity back to everyday life.

That kind of precision matters most in the smallest tasks: fastening a button, lifting a glass, holding a child’s hand.

“These aren’t just movements,” Yeo said. “They’re freedoms.”

For Yeo, the idea of restoring freedom through movement has driven his research from the very beginning.

A Mission Rooted in Loss

Yeo's work is deeply personal. His path to biomedical engineering began with loss — the sudden death of his father while Yeo was still in college. That moment reshaped his sense of purpose, redirecting his focus from machines that move to technologies that heal.

“Initially, I was thinking about designing cars,” he said. “But after my father’s death, I kind of woke up. Maybe I could do something that helps save someone’s life.”

That purpose continues to guide his lab’s work today, building technologies that help people recover what they’ve lost.

Achieving that vision, however, means tackling some of engineering’s toughest challenges.

Soft Machines, Hard Problems

Creating lifelike muscles isn’t easy. They need to be soft but strong, responsive but safe. And they must avoid triggering the body’s immune system. That means building materials that can survive inside the body — and learn to belong there.

“We always think about not only function, but adaptability,” Yeo said. “If it’s going to be part of someone’s body, it has to work with them, not against them.”

His team calibrates these synthetic fibers like precision instruments — tested, adjusted, and re-tuned until they operate in sync with the body’s natural movements. Over time, they develop a kind of “muscle memory,” adapting fluidly to changing conditions. That dynamic adaptability, Yeo explained, is what separates a machine from a prosthetic that truly feels alive.

From Collaboration to Innovation

Solving problems this complex requires more than one discipline. It takes an entire ecosystem of collaboration. Yeo’s lab brings together experts in mechanical engineering, materials science, medicine, and computer science to design smarter, safer devices.

“You can’t solve this kind of problem in isolation,” he said. “We need all of it — polymers, artificial intelligence, biomechanics — working together.”

That collaborative model is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institutes of Health, and Georgia Tech’s Institute for Matter and Systems. In 2023, Yeo received a $3 million NSF grant to train the next generation of engineers building smart medical technology.

His team now works closely with healthcare providers and industry partners to bring these devices out of the lab and into patients’ lives.

The Future You Can Feel

The future of robotics, according to Yeo, won’t be defined by power or complexity but by feel.

“If it feels foreign, people won’t use it,” he said. “But if it feels like part of you, that’s when it can truly change lives.”

It’s the opposite of The Terminator, where machines replace us. Yeo is designing these machines to help us reclaim ourselves.

Michelle Azriel Writer/Editor, Research Communications

Georgia CTSA - Informatics Expert Series

REGISTER HERE

Jane Lowers

Assistant Professor

Division of Palliative Medicine

Emory University School of Medicine

Peatlands’ ‘Huge Reservoir’ of Carbon at Risk of Release

Oct 23, 2025 —

This story by Caitlin Hayes is shared jointly with the Cornell Chronicle newsroom.

Study co-author Joel E. Kostka is the Tom and Marie Patton Distinguished Professor and associate chair for Research in the School of Biological Sciences with a joint appointment in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. He also serves as faculty director of Georgia Tech for Georgia's Tomorrow.

The Kostka Lab works in peatland ecosystems to quantify changes in microbial communities brought on by climate change drivers. In particular, next generation gene sequencing and omics approaches are employed to investigate the microbial groups that mediate organic matter degradation and the release of greenhouse gases.

Peatlands make up just 3% of the earth’s land surface but store more than 30% of the world’s soil carbon, preserving organic matter and sequestering its carbon for tens of thousands of years. A new study sounds the alarm that an extreme drought event could quadruple peatland carbon loss in a warming climate.

In the study, published October 23 in Science, researchers find that, under conditions that mimic a future climate (with warmer temperatures and elevated carbon dioxide), extreme drought dramatically increases the release of carbon in peatlands by nearly three times. This means that droughts in future climate conditions could turn a valuable carbon sink into a carbon source, erasing between 90 and 250 years of carbon stores in a matter of months.

“As temperatures increase, drought events become more frequent and severe, making peatlands more vulnerable than before,” said Yiqi Luo, senior author and the Liberty Hyde Bailey Professor in the School of Integrative Plant Science’s Soil and Crop Sciences Section, in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) at Cornell University. “We add new evidence to show that with peatlands, the stakes are high. We observed that these extreme drought events can wipe out hundreds of years of accumulated carbon, so this has a huge implication.”

“To me, this study is striking in that it shows that around 10 to 100 years of carbon uptake by one of the most important global soil carbon stores can be erased by just two months of extreme drought,” adds Joel Kostka, Tom and Marie Patton Distinguished Professor in Biological Sciences at Georgia Tech.

It was already well-established that drought reduces ecosystem productivity and increases carbon release in peatlands, but this study is the first to examine how that carbon loss is exacerbated as the planet warms and more carbon dioxide enters the atmosphere. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates extreme drought will become 1.7 to 7.2 times more likely in the near future.

Read the full story in the Cornell newsroom.

###

Other co-authors include Cornell postdoctoral researchers Jian Zhou and Ning Wei; senior research associate Lifen Jiang; and researchers from Georgia Institute of Technology, Florida State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), ETH Zurich, Northern Arizona University, the Australian National University, the University of Western Ontario and Duke University.

Funding for the study came in part from the National Science Foundation, USDA, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets.

Media contacts:

Jess Hunt-Ralston

Director of Communications

College of Sciences

Georgia Tech

Kaitlyn Serrao

Media Relations

Cornell University

Natalia Burgess

Media Assistant

ANU Communications and Engagement

The Australian National University

IBB Core Facilities Educational Seminar

Join us to learn how to better leverage the incredible resources available via your IBB Core Facilities! Revity will present a seminar on the basic and advanced features and applications of the IVIS Spectrum series of optical tomography instruments. This technology is available at IBB!

Lunch provided to in-person attendees, while supplies last. No registration required.

Keiretsu Encore: A New Channel to Reconnect with High-Quality Deal Flow

If you are a Georgia Tech student, faculty, employee you ARE a Keiretsu academic partner and the monthly meetings are FREE. GT spots are limited, so register ASAP.

REGISTER HERE - Registration is required by Monday, November 10 at 10:00 a.m.

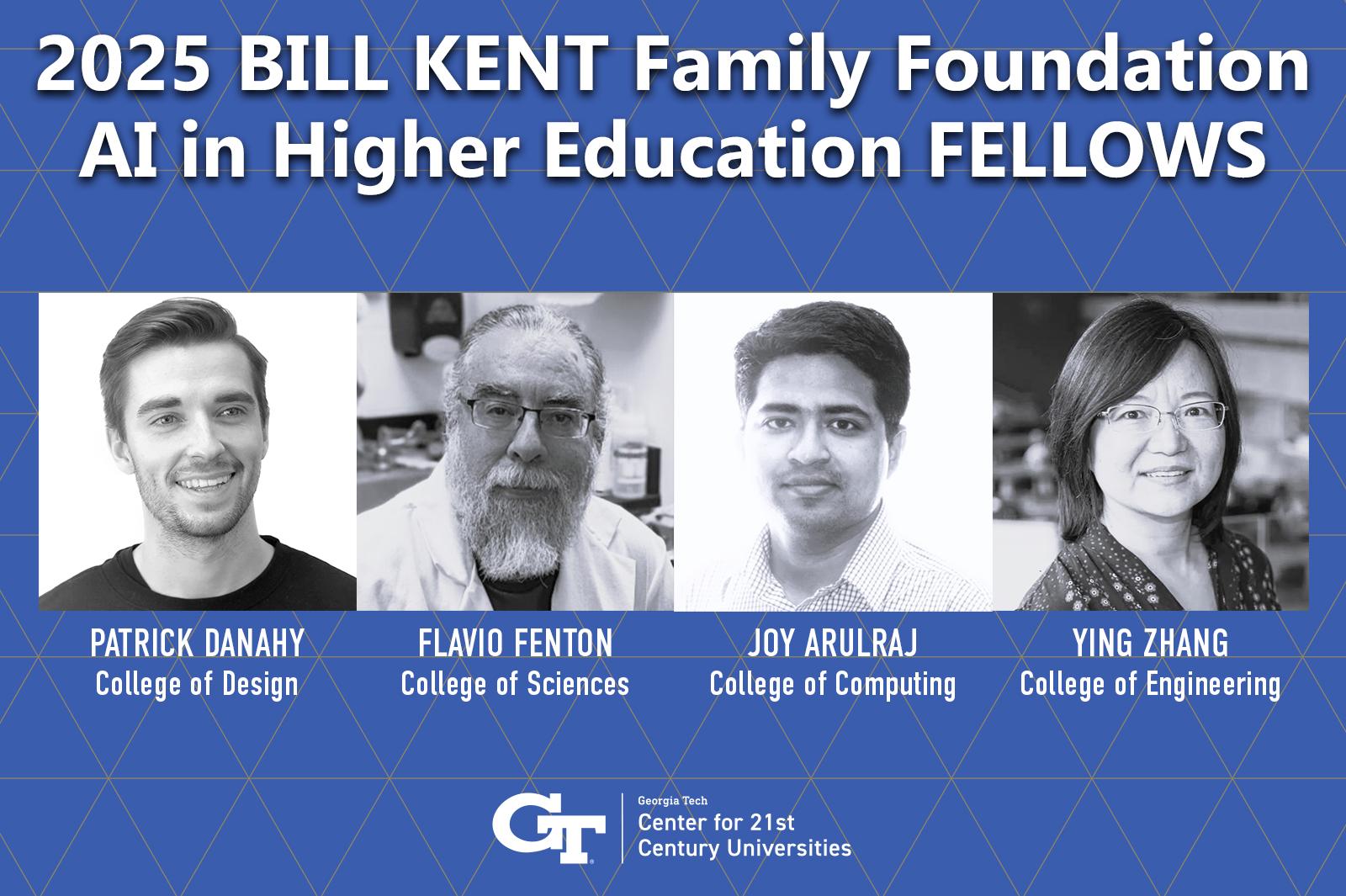

C21U Announces Inaugural Bill Kent AI in Higher Education Fellows

Oct 20, 2025 —

The Center for 21st Century Universities (C21U) has announced the inaugural cohort of Bill Kent Family Foundation AI in Higher Education Faculty Fellows for 2025–26. This C21U-led fellowship program supports faculty projects that explore innovative, ethical, and impactful uses of artificial intelligence in teaching and learning.

The fellows are Professor Flavio Fenton from the College of Sciences, Joy Arulraj from the College of Computing, Patrick Danahy from the College of Design, and Professor and Associate Chair of the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Ying Zhang, from the College of Engineering. Each fellow will lead a project that advances AI’s role in higher education.

“We deeply appreciate the generosity of the Dr. Bill Kent family in establishing this first philanthropic gift to our new College. Their generous support will allow us to encourage practical applications of AI and foster an appreciation for its ethical use,” said William Gaudelli, inaugural dean of the Georgia Tech College of Lifetime Learning. “This Fellowship will ensure we grow and learn about its use thoughtfully, developing highly innovative and engaging pedagogical experiences for all life’s stages.”

Arulraj’s TokenSmith: Fast, Local, Citable LLM Tutoring introduces a privacy-conscious AI tutoring system for database courses that provides verifiable, course-aligned answers. Fenton’s AI as a Learning Assistant develops AI-enabled instructional modules for physics, neuroscience, and scientific writing to improve conceptual understanding and promote ethical AI use. Danahy’s AI-Enabled Design Ideation and Robotic 3D Printing with Open-Source Platforms integrates AI-driven design and robotic fabrication into architecture education while addressing ethics and sustainability. Zhang’s AI-Enabled Personalized Engineering Education expands personalized learning in large engineering courses through AI tutoring frameworks and integrates AI literacy into the curriculum.

“The Bill Kent Family Fellowship gives our faculty the resources and flexibility to experiment with AI in ways that directly benefit students and inform the future of higher education,” said Stephen Harmon, executive director of C21U.

The fellowship received 21 applications from all seven Georgia Tech colleges, reflecting the educational AI subject-matter experts for their units and the Institute as a whole. Fellows will develop and implement their projects during the 2025–26 academic year and share outcomes through C21U Learning Labs and other campus events.

The Bill Kent Family Foundation partnered with C21U to establish this fellowship and support faculty innovation at Georgia Tech. Through this program, the Foundation invests in projects that explore responsible and impactful uses of artificial intelligence in teaching and learning. By funding this initiative, the Foundation aims to empower educators to develop scalable instructional models, promote ethical AI practices, and prepare students for a future shaped by emerging technologies.

Yelena M. Rivera-Vale, M.A. (she/her(s)/ella)

Communications Program Manager

Center for 21st Century Universities

College of Lifetime Learning

Georgia Institute of Technology

Strategic, Learner, Relator, Intellection, Input

Cancer Atlas Offers a Roadmap to Detecting Tumors Earlier Than Ever

Oct 16, 2025 —

(Illustration: Sarah Collins)

When a Georgia Tech-led project received a contract award from the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), it was for a bold idea with aggressive metrics. And it wasn’t guaranteed money. The team, led by biomedical engineer Gabe Kwong, had to deliver on its vision. Doing so could transform cancer screening and care, leading to one-size-fits-all tests that detect multiple cancers before they’re visible on CT or PET scans.

It’s a big goal, but that’s the point of ARPA-H. The agency funds staggeringly difficult healthcare innovation ideas that require major investment to succeed.

Two years into the $49.5 million project, Kwong and the team from Georgia Tech, Columbia University, and Mount Sinai Health System has crossed a critical threshold.

They’ve built the first tool able to measure enzyme activity around cancer tumors and healthy cells. And they’ve deployed it to understand the unique signatures for tumors from 14 different kinds of cancer.

That data is powering the first version of a cancer “atlas.” Like a geographical atlas, it will offer directions to each kind of tumor, allowing scientists to design sensors that follow the map and detect cancer tumors when they’re still small.

“If I want to deliver a sensor to a particular region inside the body, right now, there's no way of directing it. We give it systemically, and it basically infuses all tissues all the time,” said Kwong, Robert A. Milton Professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering. “What's powerful is that we’re now defining tissue sites with a specific molecular ‘barcode.’ Then if a sensor is given systemically, it should only turn on when the barcode matches the local tissue.”

Read more about the project on the College of Engineering website.

Joshua Stewart

College of Engineering