Mentoring the Future of Nanotechnology

Jul 19, 2024 — Atlanta, GA

Marissa Moore and Blair Brettmann in the lab. Credit: Allison Carter

When Blair Brettmann was a sophomore at the University of Texas at Austin, her advisor told her about the National Science Foundation’s Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) program. The summer program enables undergraduates to conduct research at top institutions across the country. Brettmann spent the summer of 2005 at Cornell working in a national nanotechnology program — a defining experience that led to her current research in molecular engineering for integrated product development.

“I didn't know for sure if I wanted to attend grad school until after the REU experience,” Brettmann said. “Through it, I went to high-level seminars for the first time, and working in a cleanroom was super cool.”

Her experience was so positive that the following summer, Brettmann completed a second REU at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she eventually earned her Ph.D. Now an associate professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and School of Materials Science and Engineering and an Institute for Matter and Systems faculty member and an initiative lead for the Renewable Bioproducts Institute, Brettmann is an REU mentor for the current iteration of the nanotechnology program — now taking place at Georgia Tech.

Brettmann’s mentee this summer, Marissa Moore, is having a similarly positive experience. A rising senior in chemical engineering at the University of Missouri-Columbia (Mizzou), Moore was already familiar with Georgia Tech because her father received his chemical engineering Ph.D. from the Institute; she hopes to do the same. Her passion for research began as she grew up with her sister, who had cerebral palsy and epilepsy.

“We spent a lot of time in hospitals trying out new devices and looking for different medications that would help her, so I knew I wanted to make a difference in this area,” she said.

But Moore wasn’t interested in being a doctor. Instead, she wanted to develop the materials that could be a solution for someone like her sister. Her undergraduate research focuses on materials and biomaterials for medical applications, and Georgia Tech is enabling her to deep-dive into pure materials science.

“What I'm working on at both universities is biodegradable polymers, but at Mizzou I’m developing that polymer from the ground up, and at Tech I’m using the properties of the polymer and finding how to make them,” she explained.

Having the opportunity to work in nanotechnology through the Institute for Materials and use Georgia Tech’s famous cleanroom made this REU stand out for Moore.

“I had never been in the cleanroom before, so that was one of the most eye-opening experiences,” she said. “It was cool to gown up and learn all of the safety precautions.”

For Brettmann, hands-on research experiences like this make the REU program unique — and crucial — for potential graduate students.

“Having your experiments fail, or even having things not turn out as you expect them to is an important part of the graduate research experience,” she said. “One of the best things about REU is it can be a first experience for people and help them decide what to do in grad school later on.”

Tess Malone, Senior Research Writer/Editor

tess.malone@gatech.edu

How the Paris Olympic Track Is Designed to Break Records

Jul 19, 2024 —

Like the track laid down at Georgia Tech before the 1996 Olympic Games, the Mondo track in Paris was engineered to produce fast times. Yellow Jacket Men's Track and Field Coach Grover Hinsdale and Principal Research Engineer Jud Ready explain the science of the surface.

Every millisecond will matter when the world's best athletes gather in Paris for the Summer Olympics, and track and field athletes will compete on a surface designed to produce record-breaking performances.

Mondo athletic tracks have been underneath the feet of Olympians since 1972. In that time, 300 records were broken on surfaces designed and constructed in Alba, Italy, including 15 at the Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta.

Consistency Is Key

Georgia Tech’s George C. Griffin Track and Field Facility was outfitted with a Mondo track before the 1996 Games to serve as the workout track for the Olympic Village, and the material has been a staple at the facility ever since. Yellow Jacket Track and Field Coach Grover Hinsdale, a coach to three Olympic gold medalists, explains that the consistency in Mondo's construction sets it apart from all other tracks.

"A Mondo track is made in a climate-controlled factory, processed from the raw rubber to the finished product. So, every square inch of Mondo is the same — same durometer, same thickness, everything is the same. All other rubberized track surfaces are poured on-site, so variables like temperature and humidity affect the result, and you may end up with lanes that don't set uniformly,” he said.

Hinsdale likened the installation process to laying carpet. It will take more than 2,800 glue pots to set the 13,000 square meters of track inside Stade de France. Jud Ready, a principal research engineer in the School of Materials Science and Engineering, says the evolution of the company’s technology has also contributed to producing faster tracks.

"They're able to alter the rubber track's energy return mechanism by changing the shape of the particulate and the compressibility of it," Ready said. "Longevity is less of a concern for the Paris track, so they can tune it to emphasize speed."

Maximizing Performance

Each layer of the track surface plays a different role in helping athletes achieve peak performance. Hinsdale describes how those layers come together with each step.

"When your foot strikes down on an asphalt surface or you're running down a sidewalk, there's virtually no give other than what's taking place in the muscles and joints of your body. The surface is giving nothing back. When your foot strikes a Mondo surface, it'll sink in slightly, and the surface gives energy back. This pushes your foot back off that track quicker, putting the foot back into the cycle to complete another stride,” he said.

Because of the energy given back by the thin and firm surface of the Mondo track, Hinsdale says, sprinters and distance runners will run faster with the same effort they normally exert on any other surface.

Athletes look for every edge to get ahead of the competition. Ready's course, Materials Science and Engineering of Sports, examines how that advantage can be found at the scientific level.

"All sports are so heavily driven by material advancements these days,” he said. “Yes, we use the mechanical properties we've used since the Egyptians started racing chariots, but as material scientists, we keep trying to make things better.”

Viewers will notice the unique purple hue of the Paris track when the games begin, but Ready and Hinsdale don't expect the striking color to affect performance.

Steven Gagliano - Institute Communications

Georgia Tech Wins Second $25 Million Award to Support Nuclear Nonproliferation Research and Education

Jul 16, 2024 — Atlanta, GA

Photo by Joya Chapman

Georgia Tech will lead a consortium of 12 universities and 12 national labs as part of a $25 million U.S. Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) award. This is the second time Georgia Tech has won this award and led research and development efforts to aid NNSA’s nonproliferation, nuclear science, and security endeavors.

The Consortium for Enabling Technologies and Innovation (ETI) 2.0 will leverage the strong foundation of interdisciplinary, collaboration-driven technological innovation developed in the ETI Consortium funded in 2019. The technical mission of the ETI 2.0 team is to advance technologies across three core disciplines: data science and digital technologies in nuclear security and nonproliferation, precision environmental analysis for enhanced nuclear nonproliferation vigilance and emergency response, and emerging technologies. They will be advanced by research projects in novel radiation detectors, algorithms, testbeds, and digital twins.

“What we're trying to do is bring those emergent technologies that are not implemented right now to fruition,” said Anna Erickson, Woodruff Professor and associate chair for research in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, who leads both grants. “We want to understand what's ahead in the future for both the technology and the threats, which will help us determine how we can address it today.”

While half the original collaborators remain, Erickson sought new institutional partners for their research expertise, including Abilene Christian University, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Stony Brook University, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and Virginia Commonwealth University. Other university collaborators include the Colorado School of Mines, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ohio State University, Texas A&M University, the University of Texas at Austin, and the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

National lab partners are the Argonne National Laboratory, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Idaho National Laboratory, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Nevada National Security Site, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratories, and Savannah River National Laboratory.

The partners, along with the other NNSA Consortia, gathered at Texas A&M in June to present the new results of the research — NNSA DNN R&D University Program Review — and the kickoff will be hosted in Atlanta in February 2025. More than 300 collaborators, including 150 students, met for four days to share their research and develop new partnerships.

Engaging students in research in the nuclear nonproliferation field is a key part of the award. The plan is to train over 50 graduate students, provide internships for graduate and undergraduate students, and offer faculty-student lab visit fellowships. This pipeline aims to develop well-rounded professionals equipped with the expertise to tackle future nonproliferation challenges.

“Because nuclear proliferation is a multifaceted problem, we try to bring together people from outside nuclear engineering to have a conversation about the problems and solutions,” Erickson said.

“One of the biggest accomplishments of ETI 1.0 is this incredible relationship that our university PIs have been able to forge with national labs,” she said. “Over five years, we've supported over 70 student internships at national labs, and we have already transitioned a number of Ph.D. students to careers at national labs.”

As the consortium efforts continue, the team looks forward to the next phase of engagement with government, university, and national lab partners.

“With a united team and a focus on cutting-edge technologies, the ETI 2.0 consortium is poised to break new ground in nuclear nonproliferation,” Erickson said. “Collaboration is the fuel, and innovation is the engine.”

Tess Malone, Senior Research Writer/Editor

tess.malone@gatech.edu

Using Deep Learning Techniques to Improve Liver Disease Diagnosis and Treatment

Jul 15, 2024 —

Professor Jun Ueda in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and robotics Ph.D. student Heriberto Nieves.

Hepatic, or liver, disease affects more than 100 million people in the U.S. About 4.5 million adults (1.8%) have been diagnosed with liver disease, but it is estimated that between 80 and 100 million adults in the U.S. have undiagnosed fatty liver disease in varying stages. Over time, undiagnosed and untreated hepatic diseases can lead to cirrhosis, a severe scarring of the liver that cannot be reversed.

Most hepatic diseases are chronic conditions that will be present over the life of the patient, but early detection improves overall health and the ability to manage specific conditions over time. Additionally, assessing patients over time allows for effective treatments to be adjusted as necessary. The standard protocol for diagnosis, as well as follow-up tissue assessment, is a biopsy after the return of an abnormal blood test, but biopsies are time-consuming and pose risks for the patient. Several non-invasive imaging techniques have been developed to assess the stiffness of liver tissue, an indication of scarring, including magnetic resonance elastography (MRE).

MRE combines elements of ultrasound and MRI imaging to create a visual map showing gradients of stiffness throughout the liver and is increasingly used to diagnose hepatic issues. MRE exams, however, can fail for many reasons, including patient motion, patient physiology, imaging issues, and mechanical issues such as improper wave generation or propagation in the liver. Determining the success of MRE exams depends on visual inspection of technologists and radiologists. With increasing work demands and workforce shortages, providing an accurate, automated way to classify image quality will create a streamlined approach and reduce the need for repeat scans.

Professor Jun Ueda in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and robotics Ph.D. student Heriberto Nieves, working with a team from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, have successfully applied deep learning techniques for accurate, automated quality control image assessment. The research, “Deep Learning-Enabled Automated Quality Control for Liver MR Elastography: Initial Results,” was published in the Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Using five deep learning training models, an accuracy of 92% was achieved by the best-performing ensemble on retrospective MRE images of patients with varied liver stiffnesses. The team also achieved a return of the analyzed data within seconds. The rapidity of image quality return allows the technician to focus on adjusting hardware or patient orientation for re-scan in a single session, rather than requiring patients to return for costly and timely re-scans due to low-quality initial images.

This new research is a step toward streamlining the review pipeline for MRE using deep learning techniques, which have remained unexplored compared to other medical imaging modalities. The research also provides a helpful baseline for future avenues of inquiry, such as assessing the health of the spleen or kidneys. It may also be applied to automation for image quality control for monitoring non-hepatic conditions, such as breast cancer or muscular dystrophy, in which tissue stiffness is an indicator of initial health and disease progression. Ueda, Nieves, and their team hope to test these models on Siemens Healthineers magnetic resonance scanners within the next year.

Publication

Nieves-Vazquez, H.A., Ozkaya, E., Meinhold, W., Geahchan, A., Bane, O., Ueda, J. and Taouli, B. (2024), Deep Learning-Enabled Automated Quality Control for Liver MR Elastography: Initial Results. J Magn Reson Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.29490

Prior Work

Robotically Precise Diagnostics and Therapeutics for Degenerative Disc Disorder

Related Material

Editorial for “Deep Learning-Enabled Automated Quality Control for Liver MR Elastography: Initial Results”

Christa M. Ernst |

Research Communications Program Manager |

Topic Expertise: Robotics, Data Sciences, Semiconductor Design & Fab |

Will the Seine River’s E. coli Woes Sink Olympic Dreams in Paris?

Jul 15, 2024 —

Time is winding down on Olympic organizers’ plans to stage open-water swimming events in Paris’ iconic Seine River later this month. The city spent $1.5 billion on new infrastructure to clean up the Seine, yet water samples continue to show high levels of potentially toxic E. coli.

The river has been closed to swimmers for the past 100 years because of pollution, but Olympic organizers hope to stage the triathlon and marathon swimming events in the water flowing in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower.

Katherine Graham has followed the saga in Paris. She’s an assistant professor in the Georgia Tech School of Civil and Environmental Engineering who studies the fate and transport of pathogens and their indicators in water, including E. coli. She said several factors are at play in the Seine.

“Paris, like most large cities, has a lot of concrete and not much dirt and grass for water to soak into."

Read the entire story on the College of Engineering website.

Jason Maderer

College of Engineering

maderer@gatech.edu

A New Neural Network Makes Decisions Like a Human Would

Jul 15, 2024 —

Getty

Humans make nearly 35,000 decisions every day, from whether it’s safe to cross the road to what to have for lunch. Every decision involves weighing the options, remembering similar past scenarios, and feeling reasonably confident about the right choice. What may seem like a snap decision actually comes from gathering evidence from the surrounding environment. And often the same person makes different decisions in the same scenarios at different times.

Neural networks do the opposite, making the same decisions each time. Now, Georgia Tech researchers in Associate Professor Dobromir Rahnev’s lab are training them to make decisions more like humans. This science of human decision-making is only just being applied to machine learning, but developing a neural network even closer to the actual human brain may make it more reliable, according to the researchers.

In a paper in Nature Human Behaviour, “The Neural Network RTNet Exhibits the Signatures of Human Perceptual Decision-Making,” a team from the School of Psychology reveals a new neural network trained to make decisions similar to humans.

Decoding Decision

“Neural networks make a decision without telling you whether or not they are confident about their decision,” said Farshad Rafiei, who earned his Ph.D. in psychology at Georgia Tech. “This is one of the essential differences from how people make decisions.”

Large language models (LLM), for example, are prone to hallucinations. When an LLM is asked a question it doesn’t know the answer to, it will make up something without acknowledging the artifice. By contrast, most humans in the same situation will admit they don’t know the answer. Building a more human-like neural network can prevent this duplicity and lead to more accurate answers.

Making the Model

The team trained their neural network on handwritten digits from a famous computer science dataset called MNIST and asked it to decipher each number. To determine the model’s accuracy, they ran it with the original dataset and then added noise to the digits to make it harder for humans to discern. To compare the model performance against humans, they trained their model (as well as three other models: CNet, BLNet, and MSDNet) on the original MNIST dataset without noise, but tested them on the noisy version used in the experiments and compared results from the two datasets.

The researchers’ model relied on two key components: a Bayesian neural network (BNN), which uses probability to make decisions, and an evidence accumulation process that keeps track of the evidence for each choice. The BNN produces responses that are slightly different each time. As it gathers more evidence, the accumulation process can sometimes favor one choice and sometimes another. Once there is enough evidence to decide, the RTNet stops the accumulation process and makes a decision.

The researchers also timed the model’s decision-making speed to see whether it follows a psychological phenomenon called the “speed-accuracy trade-off” that dictates that humans are less accurate when they must make decisions quickly.

Once they had the model’s results, they compared them to humans’ results. Sixty Georgia Tech students viewed the same dataset and shared their confidence in their decisions, and the researchers found the accuracy rate, response time, and confidence patterns were similar between the humans and the neural network.

“Generally speaking, we don't have enough human data in existing computer science literature, so we don't know how people will behave when they are exposed to these images. This limitation hinders the development of models that accurately replicate human decision-making,” Rafiei said. “This work provides one of the biggest datasets of humans responding to MNIST.”

Not only did the team’s model outperform all rival deterministic models, but it also was more accurate in higher-speed scenarios due to another fundamental element of human psychology: RTNet behaves like humans. As an example, people feel more confident when they make correct decisions. Without even having to train the model specifically to favor confidence, the model automatically applied it, Rafiei noted.

“If we try to make our models closer to the human brain, it will show in the behavior itself without fine-tuning,” he said.

The research team hopes to train the neural network on more varied datasets to test its potential. They also expect to apply this BNN model to other neural networks to enable them to rationalize more like humans. Eventually, algorithms won’t just be able to emulate our decision-making abilities, but could even help offload some of the cognitive burden of those 35,000 decisions we make daily.

Tess Malone, Senior Research Writer/Editor

tess.malone@gatech.edu

HBCU CHIPS Network Defines Organization's Strategic Direction at Atlanta Meeting

Jul 14, 2024 —

The consortium of historically Black educational institutions and other stakeholders convened to establish the organization’s strategic direction and governance model. The goal is to foster a diverse workforce and drive innovation in the U.S. semiconductor industry.

In the heart of Atlanta, members of the HBCU CHIPS Network gathered for a pivotal meeting on June 3-4, 2024. Taking place at Georgia Institute of Technology’s campus, 30-plus representatives from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), historically Black community colleges (HBCCs), nonprofit organizations, and the Institute convened to chart a new course for the microelectronics industry.

At the event, co-hosted by Clark Atlanta University (CAU) and Georgia Tech, attendees worked to establish a strategic direction for the HBCU CHIPS Network, as well as a formal operational and governance model — with the principal goals of enhancing research collaboration, positioning for CHIPS Act funding, and empowering a diverse, inclusive workforce that can meet the needs of the growing U.S. semiconductor sector.

Dietra Trent, executive director for the White House Initiative on HBCUs, attended the first day’s sessions. Frances Williams, vice president for Research and Sponsored Programs at CAU and one of the organizers and co-leaders of the HBCU CHIPS Network, welcomed the attendees and outlined the meeting agenda.

Over two days of discussion, facilitated by Michael Wilkinson, the founder of Leadership Strategies, members reframed the Network’s vision as follows: “The HBCU CHIPS Network is envisioned as a research and education consortium that serves as the nexus of collaboration and cooperation between HBCUs, government agencies, academia, and industry … Through a multidisciplinary approach, the Network will facilitate fulfilling talent pipelines to grow the workforce of the future, research innovations, resolving longstanding disparities in facilities, building out domestic capacity, and providing shared accessibility across the Network stakeholders.”

The group also established the Network’s governance and operational model, including its leadership and organizational structure.

According to George White, senior director for Strategic Partnerships at Georgia Tech and an HBCU graduate, “The outcome from this workshop has the potential to transform HBCU research collaboration and innovation well beyond the CHIPS Act. Additionally, the Network will provide outreach to community colleges, veterans, and k-12 students, empowering a diverse and inclusive workforce that leverages research innovations, including experiential learning opportunities across all stakeholder groups.”

Nationally, the network comprises five regions: the Southeast, the mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic, the Midwest, and the Southwest. Each region will have representation commensurate with their competencies and capacities in microelectronics. Selected board members within each region will constitute the leadership structure. The Network will have affiliate members that include nonprofit organizations and academic institutions like Georgia Tech.

Further, the Network identified several committees and working groups, including technical advisory, education and workforce, innovation and entrepreneurship, contracting, facilities access, communication and tech transfer, and assessment and evaluation. These committees will meet regularly and communicate status and outcomes to the larger Network.

The Network plans to host an annual conference highlighting research from participating HBCUs/HBCCs and industry partners, and the event will include a student-focused career fair.

The HBCU CHIPS Network thanks ASML, Micron, Microsoft, and Synopsys for their sponsorship.

Taiesha Smith, Sr. Program Manager, HBCU-MSI Research Partnerships

taiesha.smith@gatech.edu

Expanding Access to Obstetric Care in Georgia: Challenges and Strategies

Jul 12, 2024 —

ISyE researchers Meghan Meredith (left) and Lauren Steimle have explored maternity care deserts in depth.

Motherhood in the U.S. can be dangerous. The nation spends more on healthcare than any other high-income country. But women giving birth here — particularly Black women, and particularly in Georgia — are more likely to die in childbirth. A big reason for this maternal mortality crisis is a lack of access to obstetric care.

“Georgia has a problem with access to care — the whole country does,” said Meghan Meredith, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in the H. Milton Stewart School of Industrial and Systems Engineering (ISyE) who has spent much of her academic career studying the problem, which is particularly acute in rural, lower-income places.

Many of these places have been designated “maternity care deserts” by the March of Dimes. If a county doesn’t have any obstetric care or providers, it’s considered a desert. Another commonly used measure is whether a pregnant woman lives within 50 miles of critical care obstetrics (CCO).

These measures are often referred to in academic literature and popular media to highlight a lack of healthcare access, and by public policy leaders trying to address the issue. But it’s become evident to Georgia Tech researchers that they just don’t add up.

“These measures don’t capture the complete picture,” said Meredith. “They aren’t an accurate representation of access to care.”

And that’s what concerns Meredith and her faculty advisor, ISyE Assistant Professor Lauren Steimle.

“We’ve been interested in access to maternal care for a long time, and in countless news stories, the maternity care desert measure is reported on,” Meredith said. “We recognized the limitations, so we thought, ‘Let’s write a paper that explains how this measure is not a complete representation of access.’”

They published their work recently in the journal BMC Health Services Research.

Modeling the Landscape

To study these measures of access, Meredith and Steimle used the same kind of computer-based mathematical model that helps companies decide where to place a new distribution center, retail outlet, or even electric car charging stations: a facility location model.

“This model helps us determine where to place facilities, so demand is sufficiently covered with the fewest number of facilities,” said Steimle. “There are tons of potential applications for this model, but we’re using it for healthcare.” For this study, they used the model to identify where Georgia would need to expand healthcare facilities to improve access under the commonly used measures.

Here’s some of what the researchers found:

• Of the 1,910,308 reproductive-age women in Georgia, 104,158 (5.5%) live in maternity care deserts, while 150,563 (7.9%) live more than 50 miles from CCO services; 38,202 live in both situations.

• Fifty-six counties in Georgia meet current “maternity care desert” measures, which means eliminating these deserts would require 56 new obstetrics hospitals. That would increase the number of obstetric hospitals statewide from 83 to 139 (a 67% increase).

• Strategically expanding 16 hospitals (a 19% increase) would reduce the number of reproductive-age women living in deserts by half.

• 82% of reproductive-age women designated as living in deserts live within 25 miles from an obstetric hospital.

The researchers conclude that policymakers should be warned: Using the maternity care desert measure alone as a basis for where and how to invest in healthcare resources isn’t a great idea.

“If we really want to improve pregnancy outcomes, our measures of access should promote risk-appropriate and regionalized care systems,” Steimle said.

Turns out, Georgia is already headed in that direction.

Counting Counties: One Size Doesn’t Fit All

To illustrate the problems with the maternity care desert measure, Steimle compared Georgia with a very different state on the opposite side of the U.S.: Nevada.

“A major problem with the maternity care desert measure is its emphasis on county-by-county infrastructure,” she said. “It’s a one-size-fits-all approach that doesn’t tell the whole story about access to care.”

For example, Georgia has 159 counties and more than three times the population of Nevada. Meanwhile, Nevada has twice the square mileage of Georgia — and 16 very large counties.

At 18,147 square miles, Nye County is Nevada’s largest, and it’s been labeled a maternity care desert. There’s also lots of actual desert in Nye, which is larger than nine U.S. states. So, it’s difficult to accurately compare a vast jurisdiction like Nye with, say, central Georgia’s Lamar County. Lamar, also labeled a desert, is a mere 185 square miles in size. It's also surrounded by counties that are veritable oases of care.

“A lot of people in Georgia may be falsely labeled as not having access, at least geographically speaking, when in fact they have services nearby,” noted Steimle. “Meanwhile, in a state like Nevada, some women may be labeled as having access, but might be very far from obstetric hospitals in their county.”

Steimle also point out that measuring access on a county-by-county basis ignores efforts to coordinate care across the whole state. “The maternity care desert model doesn’t hold up. And it doesn't reflect Georgia’s approach to a regionalization system.”

Since 2009, the Georgia Department of Public Health has organized the state into six geographic perinatal regions (the perinatal period covers pregnancy, childbirth, and early postpartum). The idea is to coordinate the delivery of health services to ensure people in all regions have access to risk-appropriate maternal care.

Build a Better Model

Each of Georgia’s perinatal regions has a “hub” — a major care center serving as an administrative unit to enable the coordination and delivery of maternal care services. For example, The Emory Perinatal Regional Center at Emory University Hospital is the coordinating center for the 39-county metro Atlanta region.

This regionalization strategy also tries to address the problem of hospital closures, a troubling trend that leads to more deserts. In Georgia, 12 hospitals have closed since 2013; 18 rural hospitals are currently at risk of closure. And this new Georgia Tech study indicates that Georgia would somehow need to add 56 new facilities to eliminate the state’s maternity care deserts — at least by the standards used by the March of Dimes.

“Eliminating maternity care deserts in Georgia would mean adding a larger number of obstetrics facilities to make sure every county has an obstetric hospital,” Steimle said. “But this is likely unrealistic with the current economic forces pushing hospitals to close their obstetric units. With that many facilities in Georgia, some facilities would have a very small number of deliveries, which is not economically sustainable.”

In other words, eliminating maternity care deserts in Georgia wouldn’t sufficiently address the larger problems related to access to care. Instead, Steimle and Meredith advocate for approaches that simultaneously consider the different dimensions of an ideal maternal healthcare system, not just access alone.

For this initial study, Steimle and Meredith just focused on spatial access. They haven’t yet addressed the complex issues of racial disparities, insurance access, or other hurdles facing reproductive-age women in Georgia. That may be coming.

“This is a start,” Steimle said. “Our future work entails thinking about how to come at this with the goal of maximizing or improving outcomes for women.”

And as policy leaders across the country begin to address the maternal mortality crisis, Steimle believes her team’s approach using more sophisticated tools can be helpful. So far, they’ve shared their results with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and members of the Georgia, Iowa, and Nevada departments of public health.

“How do we make measurements that point us toward our end goals? Our tools as mathematical modelers can really help us think through the system holistically and think through strategies before trying them in the real world,” Steimle said. “Think of it as a policy sandbox.”

CITATION: Meghan Meredith, Lauren Steimle, and Stephanie Radke. “The implications of using maternity care deserts to measure progress in access to obstetric care: a mixed-integer optimization analysis.” BMC Health Services Research (June 2024)

New Machine Learning Method Lets Scientists Use Generative AI to Design Custom Molecules and Other Complex Structures

Jul 12, 2024 —

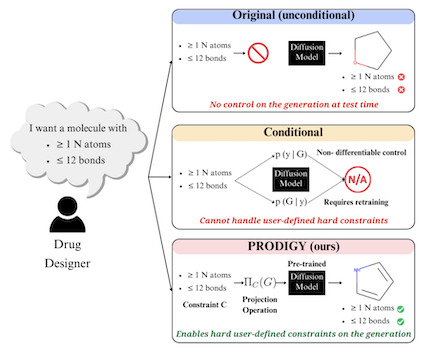

New research from Georgia Tech is giving scientists more control options over generative artificial intelligence (AI) models in their studies. Greater customization from this research can lead to discovery of new drugs, materials, and other applications tailor-made for consumers.

The Tech group dubbed its method PRODIGY (PROjected DIffusion for controlled Graph Generation). PRODIGY enables diffusion models to generate 3D images of complex structures, such as molecules from chemical formulas.

Scientists in pharmacology, materials science, social network analysis, and other fields can use PRODIGY to simulate large-scale networks. By generating 3D molecules from multiple graph datasets, the group proved that PRODIGY could handle complex structures.

In keeping with its name, PRODIGY is the first plug-and-play machine learning (ML) approach to controllable graph generation in diffusion models. This method overcomes a known limitation inhibiting diffusion models from broad use in science and engineering.

“We hope PRODIGY enables drug designers and scientists to generate structures that meet their precise needs,” said Kartik Sharma, lead researcher on the project. “It should also inspire future innovations to precisely control modern generative models across domains.”

PRODIGY works on diffusion models, a generative AI model for computer vision tasks. While suitable for image creation and denoising, diffusion methods are limited because they cannot accurately generate graph representations of custom parameters a user provides.

PRODIGY empowers any pre-trained diffusion model for graph generation to produce graphs that meet specific, user-given constraints. This capability means, as an example, that a drug designer could use any diffusion model to design a molecule with a specific number of atoms and bonds.

The group tested PRODIGY on two molecular and five generic datasets to generate custom 2D and 3D structures. This approach ensured the method could create such complex structures, accounting for the atoms, bonds, structures, and other properties at play in molecules.

Molecular generation experiments with PRODIGY directly impact chemistry, biology, pharmacology, materials science, and other fields. The researchers say PRODIGY has potential in other fields using large networks and datasets, such as social sciences and telecommunications.

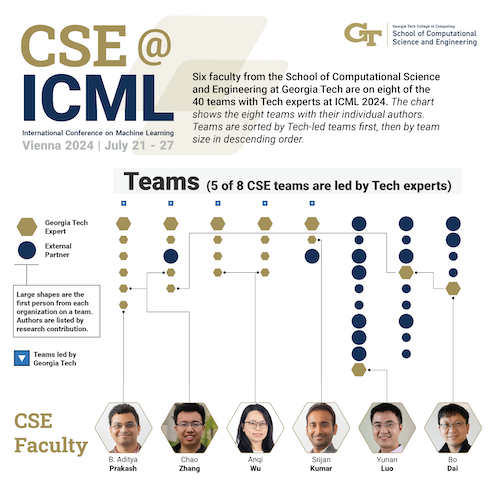

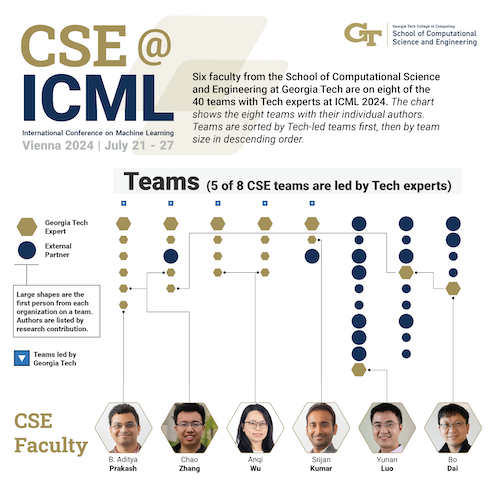

These features led to PRODIGY’s acceptance for presentation at the upcoming International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2024). ICML 2024 is the leading international academic conference on ML. The conference is taking place July 21-27 in Vienna.

Assistant Professor Srijan Kumar is Sharma’s advisor and paper co-author. They worked with Tech alumnus Rakshit Trivedi (Ph.D. CS 2020), a Massachusetts Institute of Technology postdoctoral associate.

Twenty-four Georgia Tech faculty from the Colleges of Computing and Engineering will present 40 papers at ICML 2024. Kumar is one of six faculty representing the School of Computational Science and Engineering (CSE) at the conference.

Sharma is a fourth-year Ph.D. student studying computer science. He researches ML models for structured data that are reliable and easily controlled by users. While preparing for ICML, Sharma has been interning this summer at Microsoft Research in the Research for Industry lab.

“ICML is the pioneering conference for machine learning,” said Kumar. “A strong presence at ICML from Georgia Tech illustrates the ground-breaking research conducted by our students and faculty, including those in my research group.”

Visit https://sites.gatech.edu/research/icml-2024 for news and coverage of Georgia Tech research presented at ICML 2024.

Bryant Wine, Communications Officer

bryant.wine@cc.gatech.edu

Hybrid Machine Learning Model Untangles Web of Communication in the Brain

Jul 11, 2024 —

A new machine learning (ML) model created at Georgia Tech is helping neuroscientists better understand communications between brain regions. Insights from the model could lead to personalized medicine, better brain-computer interfaces, and advances in neurotechnology.

The Georgia Tech group combined two current ML methods into their hybrid model called MRM-GP (Multi-Region Markovian Gaussian Process).

Neuroscientists who use MRM-GP learn more about communications and interactions within the brain. This in turn improves understanding of brain functions and disorders.

“Clinically, MRM-GP could enhance diagnostic tools and treatment monitoring by identifying and analyzing neural activity patterns linked to various brain disorders,” said Weihan Li, the study’s lead researcher.

“Neuroscientists can leverage MRM-GP for its robust modeling capabilities and efficiency in handling large-scale brain data.”

MRM-GP reveals where and how communication travels across brain regions.

The group tested MRM-GP using spike trains and local field potential recordings, two kinds of measurements of brain activity. These tests produced representations that illustrated directional flow of communication among brain regions.

Experiments also disentangled brainwaves, called oscillatory interactions, into organized frequency bands. MRM-GP’s hybrid configuration allows it to model frequencies and phase delays within the latent space of neural recordings.

MRM-GP combines the strengths of two existing methods: the Gaussian process (GP) and linear dynamical systems (LDS). The researchers say that MRM-GP is essentially an LDS that mirrors a GP.

LDS is a computationally efficient and cost-effective method, but it lacks the power to produce representations of the brain. GP-based approaches boost LDS's power, facilitating the discovery of variables in frequency bands and communication directions in the brain.

Converting GP outputs into an LDS is a difficult task in ML. The group overcame this challenge by instilling separability in the model’s multi-region kernel. Separability establishes a connection between the kernel and LDS while modeling communication between brain regions.

Through this approach, MRM-GP overcomes two challenges facing both neuroscience and ML fields. The model helps solve the mystery of intraregional brain communication. It does so by bridging a gap between GP and LDS, a feat not previously accomplished in ML.

“The introduction of MRM-GP provides a useful tool to model and understand complex brain region communications,” said Li, a Ph.D. student in the School of Computational Science and Engineering (CSE).

“This marks a significant advancement in both neuroscience and machine learning.”

Fellow doctoral students Chengrui Li and Yule Wang co-authored the paper with Li. School of CSE Assistant Professor Anqi Wu advises the group.

Each MRM-GP student pursues a different Ph.D. degree offered by the School of CSE. W. Li studies computer science, C. Li studies computational science and engineering, and Wang studies machine learning. The school also offers Ph.D. degrees in bioinformatics and bioengineering.

Wu is a 2023 recipient of the Sloan Research Fellowship for neuroscience research. Her work straddles two of the School’s five research areas: machine learning and computational bioscience.

MRM-GP will be featured at the world’s top conference on ML and artificial intelligence. The group will share their work at the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2024), which will be held July 21-27 in Vienna.

ICML 2024 also accepted for presentation a second paper from Wu’s group intersecting neuroscience and ML. The same authors will present A Differentiable Partially Observable Generalized Linear Model with Forward-Backward Message Passing.

Twenty-four Georgia Tech faculty from the Colleges of Computing and Engineering will present 40 papers at ICML 2024. Wu is one of six faculty representing the School of CSE who will present eight total papers.

The group’s ICML 2024 presentations exemplify Georgia Tech’s focus on neuroscience research as a strategic initiative.

Wu is an affiliated faculty member with the Neuro Next Initiative, a new interdisciplinary program at Georgia Tech that will lead research in neuroscience, neurotechnology, and society. The University System of Georgia Board of Regents recently approved a new neuroscience and neurotechnology Ph.D. program at Georgia Tech.

“Presenting papers at international conferences like ICML is crucial for our group to gain recognition and visibility, facilitates networking with other researchers and industry professionals, and offers valuable feedback for improving our work,” Wu said.

“It allows us to share our findings, stay updated on the latest developments in the field, and enhance our professional development and public speaking skills.”

Visit https://sites.gatech.edu/research/icml-2024 for news and coverage of Georgia Tech research presented at ICML 2024.

Bryant Wine, Communications Officer

bryant.wine@cc.gatech.edu