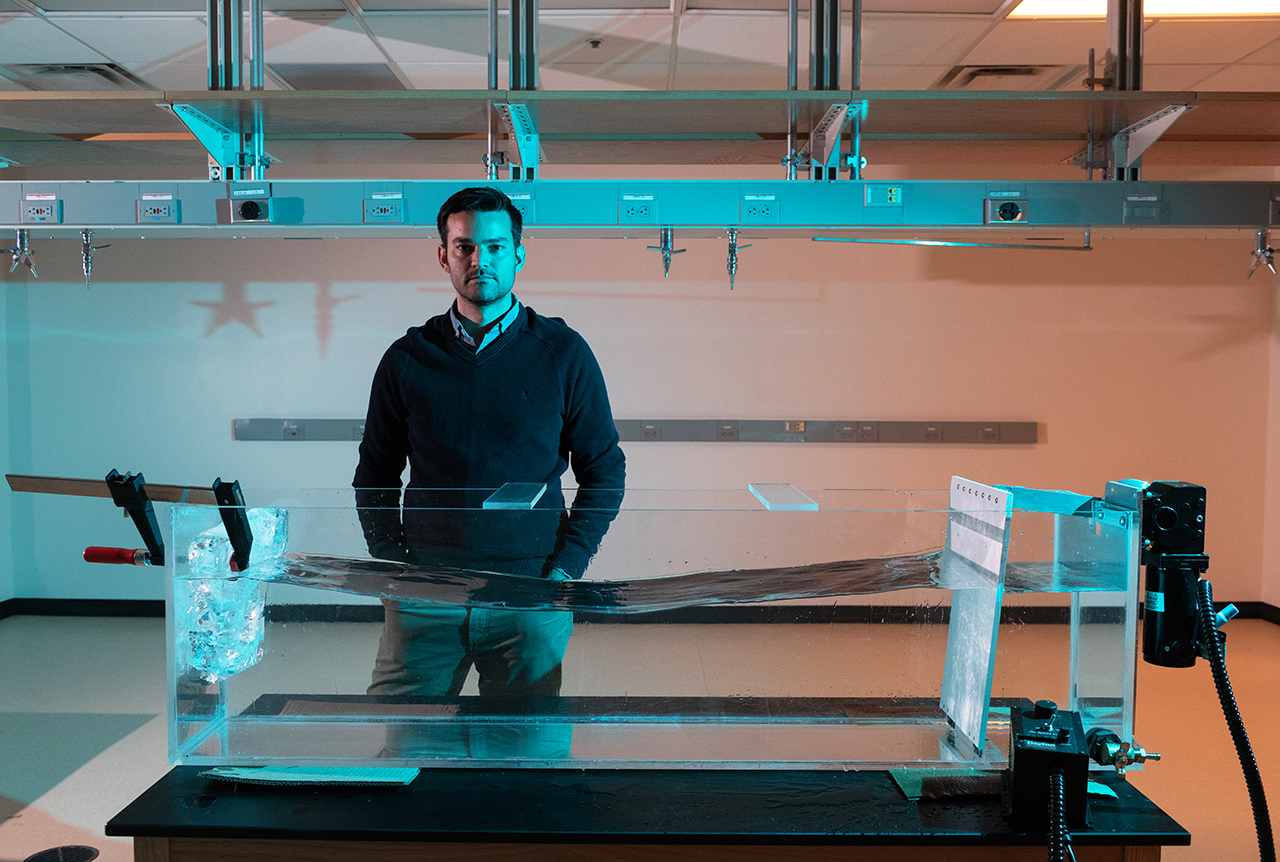

Alex Robel is improving how computer models of melting ice sheets incorporate data from field expeditions and satellites by creating a new open-access software package — complete with state-of-the-art tools and paired with ice sheet models that anyone can use, even on a laptop or home computer.

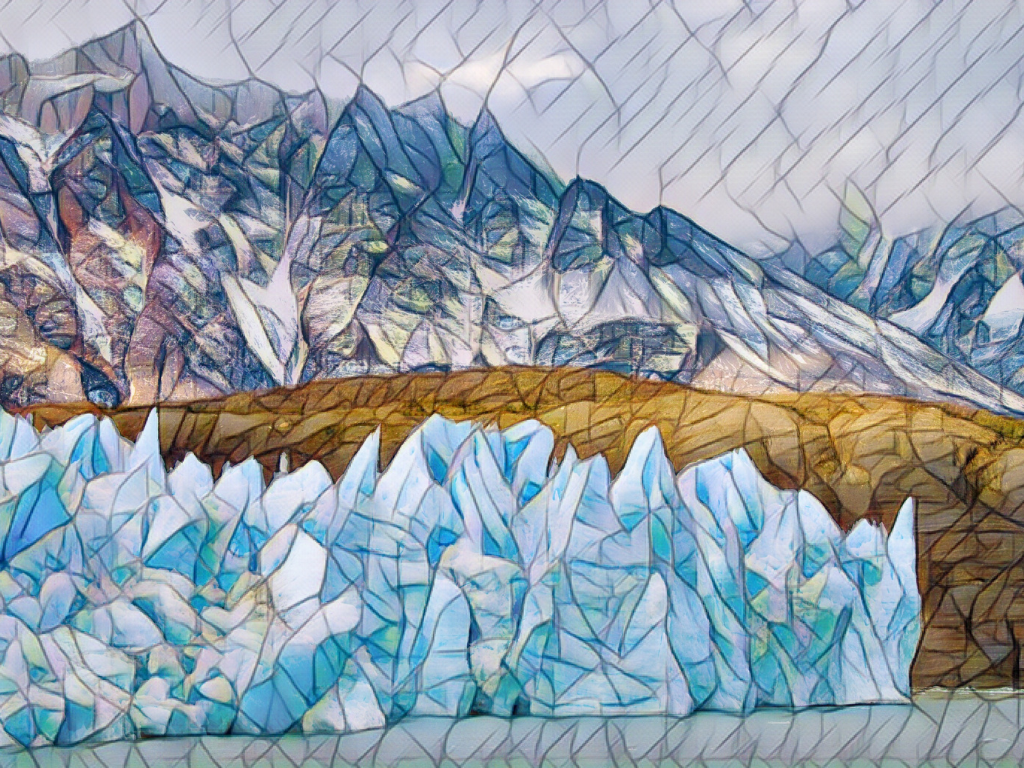

Improving these models is critical: while melting ice sheets and glaciers are top contributors to sea level rise, there are still large uncertainties in sea level projections at 2100 and beyond.

“Part of the problem is that the way that many models have been coded in the past has not been conducive to using these kinds of tools,” Robel, an assistant professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, explains. “It's just very labor-intensive to set up these data assimilation tools — it usually involves someone refactoring the code over several years.”

“Our goal is to provide a tool that anyone in the field can use very easily without a lot of labor at the front end,” Robel says. “This project is really focused around developing the computational tools to make it easier for people who use ice sheet models to incorporate or inform them with the widest possible range of measurements from the ground, aircraft and satellites.”

Now, a $780,000 NSF CAREER grant will help him to do so.

The National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Development Award is a five-year funding mechanism designed to help promising researchers establish a personal foundation for a lifetime of leadership in their field. Known as CAREER awards, the grants are NSF’s most prestigious funding for untenured assistant professors.

“Ultimately,” Robel says, “this project will empower more people in the community to use these models and to use these models together with the observations that they're taking.”

Ice sheets remember

“Largely, what models do right now is they look at one point in time, and they try their best — at that one point in time — to get the model to match some types of observations as closely as possible,” Robel explains. “From there, they let the computer model simulate what it thinks that ice sheet will do in the future.”

In doing so, the models often assume that the ice sheet starts in a state of balance, and that it is neither gaining nor losing ice at the start of the simulation. The problem with this approach is that ice sheets dynamically change, responding to past events — even ones that have happened centuries ago. “We know from models and from decades of theory that the natural response time scale of thick ice sheets is hundreds to thousands of years,” Robel adds.

By informing models with historical records, observations, and measurements, Robel hopes to improve their accuracy. “We have observations being made by satellites, aircraft, and field expeditions,” says Robel. “We also have historical accounts, and can go even further back in time by looking at geological observations or ice cores. These can tell us about the long history of ice sheets and how they've changed over hundreds or thousands of years.”

Robel’s team plans to use a set of techniques called data assimilation to adjust, or ‘nudge’, models. “These data assimilation techniques have been around for a really long time,” Robel explains. “For example, they’re critical to weather forecasting: every weather forecast that you see on your phone was ultimately the product of a weather model that used data assimilation to take many observations and apply them to a model simulation.”

“The next part of the project is going to be incorporating this data assimilation capability into a cloud-based computational ice sheet model,” Robel says. “We are planning to build an open source software package in Python that can use this sort of data assimilation method with any kind of ice sheet model.”

Robel hopes it will expand accessibility. “Currently, it's very labor-intensive to set up these data assimilation tools, and while groups have done it, it usually involves someone re-coding and refactoring the code over several years.”

Building software for accessibility

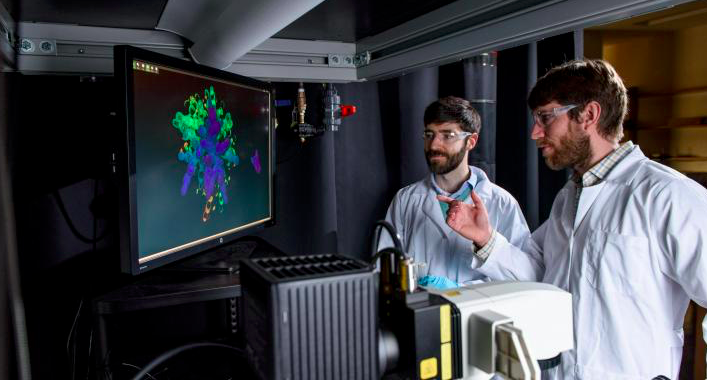

Robel’s team will then apply their software package to a widely used model, which now has an online, browser-based version. “The reason why that is particularly useful is because the place where this model is running is also one of the largest community repositories for data in our field,” Robel says.

Called Ghub, this relatively new repository is designed to be a community-wide place for sharing data on glaciers and ice sheets. “Since this is also a place where the model is living, by adding this capability to this cloud-based model, we'll be able to directly use the data that's already living in the same place that the model is,” Robel explains.

Users won’t need to download data, or have a high-speed computer to access and use the data or model. Researchers collecting data will be able to upload their data to the repository, and immediately see the impact of their observations on future ice sheet melt simulations. Field researchers could use the model to optimize their long-term research plans by seeing where collecting new data might be most critical for refining predictions.

“We really think that it is critical for everyone who's doing modeling of ice sheets to be doing this transient data simulation to make sure that our simulations across the field are all doing the best possible job to reproduce and match observations,” Robel says. While in the past, the time and labor involved in setting up the tools has been a barrier, “developing this particular tool will allow us to bring transient data assimilation to essentially the whole field.”

Bringing Real Data to Georgia’s K-12 Classrooms

The broad applications and user-base expands beyond the scientific community, and Robel is already developing a K-12 curriculum on sea level rise, in partnership with Georgia Tech CEISMC Researcher Jayma Koval. “The students analyze data from real tide gauges and use them to learn about statistics, while also learning about sea level rise using real data,” he explains.

Because the curriculum matches with state standards, teachers can download the curriculum, which is available for free online in partnership with the Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association (SECOORA), and incorporate it into their preexisting lesson plans. “We worked with SECOORA to pilot a middle school curriculum in Atlanta and Savannah, and one of the things that we saw was that there are a lot of teachers outside of middle school who are requesting and downloading the curriculum because they want to teach their students about sea level rise, in particular in coastal areas,” Robel adds.

In Georgia, there is a data science class that exists in many high schools that is part of the computer science standards for the state. “Now, we are partnering with a high school teacher to develop a second standards-aligned curriculum that is meant to be taught ideally in a data science class, computer class or statistics class,” Robel says. “It can be taught as a module within that class and it will be the more advanced version of the middle school sea level curriculum.”

The curriculum will guide students through using data analysis tools and coding in order to analyze real sea level data sets, while learning the science behind what causes variations and sea level, what causes sea level rise, and how to predict sea level changes.

“That gets students to think about computational modeling and how computational modeling is an important part of their lives, whether it's to get a weather forecast or play a computer game,” Robel adds. “Our goal is to get students to imagine how all these things are combined, while thinking about the way that we project future sea level rise.”